Words Peter Whitaker Photography Independant Observations

A history of the men who made motocross.

In the years following WW2, motorcycle scrambles flourished across the south eastern regions of Australia. Yet it was a small number of diehards who dominated: Ken Rumble, Roy Dungate, Charlie Scaysbrook, John Burrows and – believe it or not – Monty South, Charlie West and Roy East.

Riding an eclectic mix of British machines; BSA; Matchless; Velocette; AJS and Norton, it was standard practice for many top riders to contest a minimum of three classes with some entering every solo class: 125, 250, 350, 500cc and Open; often with time for no more than a longneck of Reschs Dinner Ale between events. And, with venues as far flung as Baulkham Hills in New South Wales, Tanunda in South Australia and Geelong in Victoria, it was inevitably a very long drive home for a lot of competitors.

It wasn’t until November 1953 that Ballarat Motorcycle Club hosted the inaugural Australian Scrambles Championships at nearby Korweinguboora. Finally a national championship had been established and, the following year, a huge crowd turned up to see the 1954 titles contested at Sheidow Park in South Australia.

It would certainly have surprised many competitors when the Auto Cycle Council of Australia (ACCA) nominated the Harley-Davidson Club of Western Australia to host the 1955 Australian Scrambles Championships. Unsurprisingly the West Aussies already had their own notion about scrambling, having held their first event adjacent to the WA Rope Works Factory near Buckland Hill in 1928.

The original start line was located half-way along the main road from Perth to Fremantle, the course crossed the peninsula between the Indian Ocean and the Swan River to Billygoat Farm for a lunch stop, before looping back to Buckland Hill in the afternoon. Marked by arrows and flags the total distance was 10 miles (16km) with the regulations stating “provided a competitor does not miss any of the course, he is at liberty to go as he pleases, so long as he gets to the finishing line quickly.”

The organisers, Roy Charman and Aubrey Melrose, had adopted the concept from Britain where they had both raced in the Isle of Man TT and earned factory rides in several cross-country trials, including the International Six Day Trial.

It wasn’t until 1982 that the term Enduro replaced Trial, so Charman and Melrose hedged their bets by announcing the event as the 1928 TT Scramble. Even this title meant little to the reporter at the West Australian, who headlined the proposed event as ‘The Harley Scramble’. A name which stuck for a race which went on to become the blue-riband event of Western Australian motorcycling for almost four decades.

Ken Vincent did the host club proud, winning the inaugural race aboard his 1200cc Harley-Davidson in little more than 30 minutes; a time indicative of the severity of conditions. With but a single five-mile (8km) lap in the morning and a second in the afternoon there were only three finishers; yet both competitors and spectators considered proceedings a great success. And, despite the mechanical problems which more than decimated the field in the inaugural race the second scramble the following year would be a shortened loop, but held over six laps – a total distance of 30 miles over a course that had been changed with a view to making it a lot more delightful for the spectators.

According to the West Australian newspaper, “the course included 75 different bends, 25 hairpin turns, eight slides, seven sharp ascents and about 200 smaller bends. For the greater part the track is only about a foot wide.” The Harley Scramble title had stuck, though the newspaper’s description was that of a classic enduro loop.

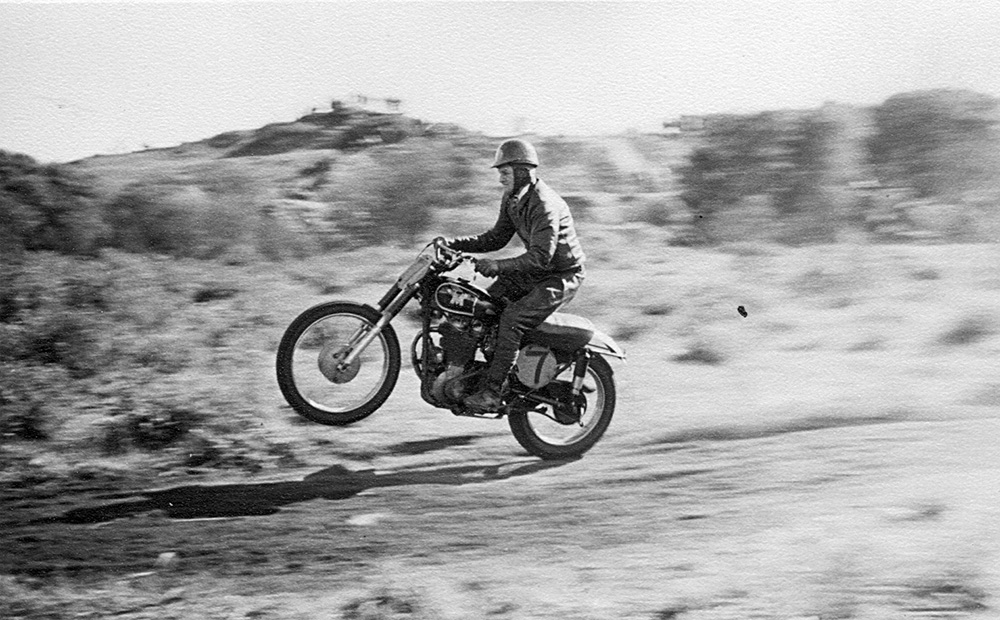

With packs of Harley V-twins and suchlike thundering through the ti-trees and clumps of beach spinifex, it took no time at all to create passing opportunities, but lack of crowd control on the outlying sections of the course was a concern. Over successive years the track length was reduced to five miles, then three, before, in its final configuration of two-and-a-half miles when it became known as the Ropeworks. Encompassing a limestone quarry, several 10-metre sand dunes so steep that rope-and-tackle teams were required to assist riders – or at least clear them from the racing line. The track was so punishing on machinery it’s been reported competitors took to burying replacement wheels and chains around the track for a better chance at seeing the finish.

Within a decade of its inception, the Harley Scramble had evolved into what was probably Australia’s first natural terrain motocross track; provided an abandoned limestone quarry qualified as natural terrain. Regardless of race distance and competitor numbers, the Harley Scramble remained a scratch race, with riders despatched in pairs at 10-second intervals. In addition to the Melrose Cup, trophies were awarded to 250cc, 350cc, 500cc and Open Classes.

Prior to WW2 the Harley-Davidson host club dominated, with eight wins to the heavy V-twins, despite their lack of agility in loose sand. As early as 1931, Melrose demonstrated what a lightweight BSA 250 was capable of by taking victory. The final pre-WW2 event featured both a Junior and Senior Scramble pitting a small fleet of 350cc BSAs against a couple of 1000cc Harleys and, for the first time, a shotgun start – later abandoned because of the safety risk.

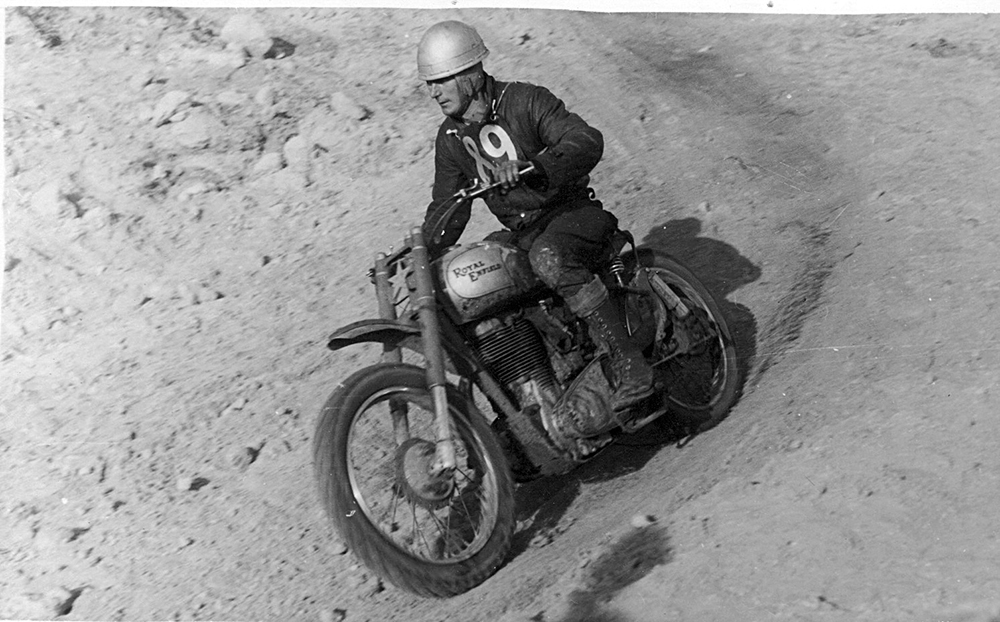

Post-war, it became obvious that a 52km race in the morning followed by a 73km session in the afternoon was more than a handful for the American V-twins. When George Scott and Peter Nicol took three wins apiece between 1949 and 1954 on BSA and Royal Enfield singles; Harley-Davidson’s heyday was over.

Yet scrambling had established such an enthusiastic following in the west, it was politic to have the most isolated city on the planet host the 1955 Australian titles, even though travel costs prevented many regular eastern-state competitors from making the journey. New South Wales champion Charlie Scaysbrook made the long trek, as did Les Sheehan and Jim Silvey, the Victorian and South Australian title holders.

The ACCA had earmarked 250 quid to induce a couple of overseas riders to compete, however the money was never claimed and might have been better spent luring a couple of Tasmanians over the water. Yet the West Aussies were never reliant on out-of-towners and a record number of 112 competitors fronted the starter for Sunday morning’s 10-lapper in front of 20,000 spectators.

Almost a quarter of the field did not survive the morning session, though the three eastern state champions battled through with Sheehan in the lead. The 14-lap afternoon session was a different story though, when the Ropeworks took its toll, breaking the frame of Sheehan’s ex-works 500cc AJS, and Scaysbrook seizing the motor on his 350cc Matchless when he lost the cap from the oil tank. Silvey finished the gruelling afternoon event but was no match for local hero Peter Nicol who, in taking his hat-trick at the venue, won both the 350cc division and Outright honours.

Later the Ropeworks course was modified yet again and became the venue for the 1962 Australian Scrambles Championship. Two years later in 1964, a 100km motocross run over the 4.2km circuit was the last event before the Mosman Shire Council allowed developers to take advantage of the coastal views.

Now instead of memorable whoops such as Percy’s Leap, Charman’s Horror, Wilkie’s Wobble and Double Descent, passers-by can only look upon row after row of anonymous McMansions.