The rise and fall of the Castrol Six Hour Production Race

The FJ Holden and the Skyline Drive-In were beyond the horizon when the dawn of the fabulous 1950s generated over 27,000 new motorcycle registrations across Australia. Then Hollywood gave us mumblin’ Marlon in The Wild One before Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller followed with their memorable ‘black denim trousers and motorcycle boots, and a black leather jacket with an eagle on the back’ lyrics. And despite Honda’s claim that ‘you meet the nicest people on a Honda’, the hoon on the Harley became the felonious face of motorcycling. By the end of the decade, new motorcycle registrations dropped to less than 10,000 a year.

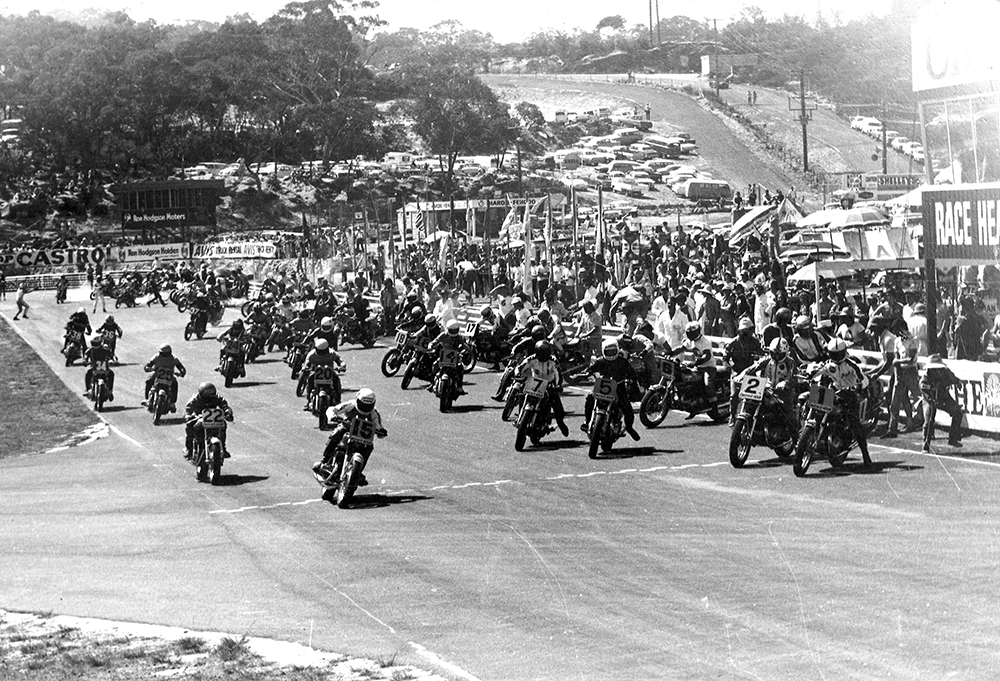

The start of something big; the 1970 6 Hour

The start of something big; the 1970 6 Hour

For many years the influential Willoughby District Motor Cycle Club (WDMCC) had ignored the controversy over bikie gangs, concentrating on promoting scrambles at Moorebank and road racing at Mount Druitt. To promote the new Amaroo Park complex in collaboration with the Australian Racing Drivers Club, the WDMCC identified the 1.9km hotmix circuit would be an ideal venue for a signature road racing event such as the Hardie Ferodo 1000 at Mount Panorama. Castrol oils agreed and anted up $1000 for the naming rights.

Strictly for shiny new production bikes with no deviation from standard specifications, the concept revitalised the motorcycle industry; even the air in the tyres had to be ‘showroom’.

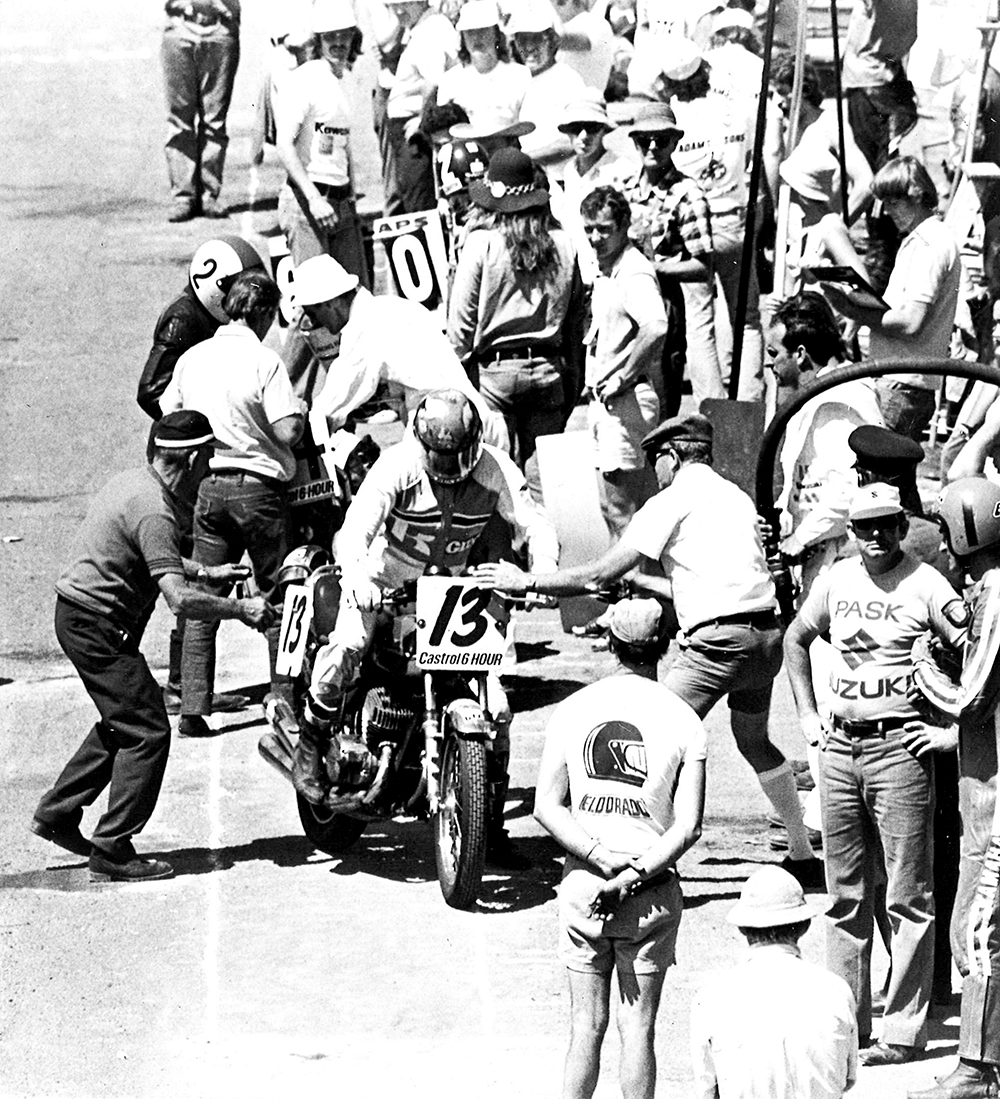

Gregg Hansford climbs onto the Kawasaki H2 he shared with Rob Hinton. They ran out of brakes in the final hour

Gregg Hansford climbs onto the Kawasaki H2 he shared with Rob Hinton. They ran out of brakes in the final hour

When the WDMCC announced the largest purse on offer in Australian motorcycle racing –$3000 plus contingency money – over 70 entries powered in. The inaugural ‘Castrol 1000’, held in October 1970, generated widespread interest, and stamped a positive spin on motorcycling while, in hindsight, simultaneously confirmed the demise of the British motorcycle industry. Because although Len Atlee’s 650cc Triumph Bonneville won by a margin of four laps, it would be the last time until the turn of the century a British machine would win a production race Down Under. It was a sign of things to come when a Suzuki T250 was only two laps adrift of the second-placed Honda CB500.

Neil Chivas leans on the wall in 1977

Neil Chivas leans on the wall in 1977

Fresh from its success at Mount Panorama, Channel 7 broadcast the 1971 event live to 750,000 couch potatoes – many of whom sat through the entire Castrol Six Hour Production Race.

In relocating from the festering mud of the Moorebank scrambles circuit, the WDMCC had created a remarkable halo event, just as likely to be featured in the hugely popular Australian Womens Weekly as it was in the less refined pages of People and Post.

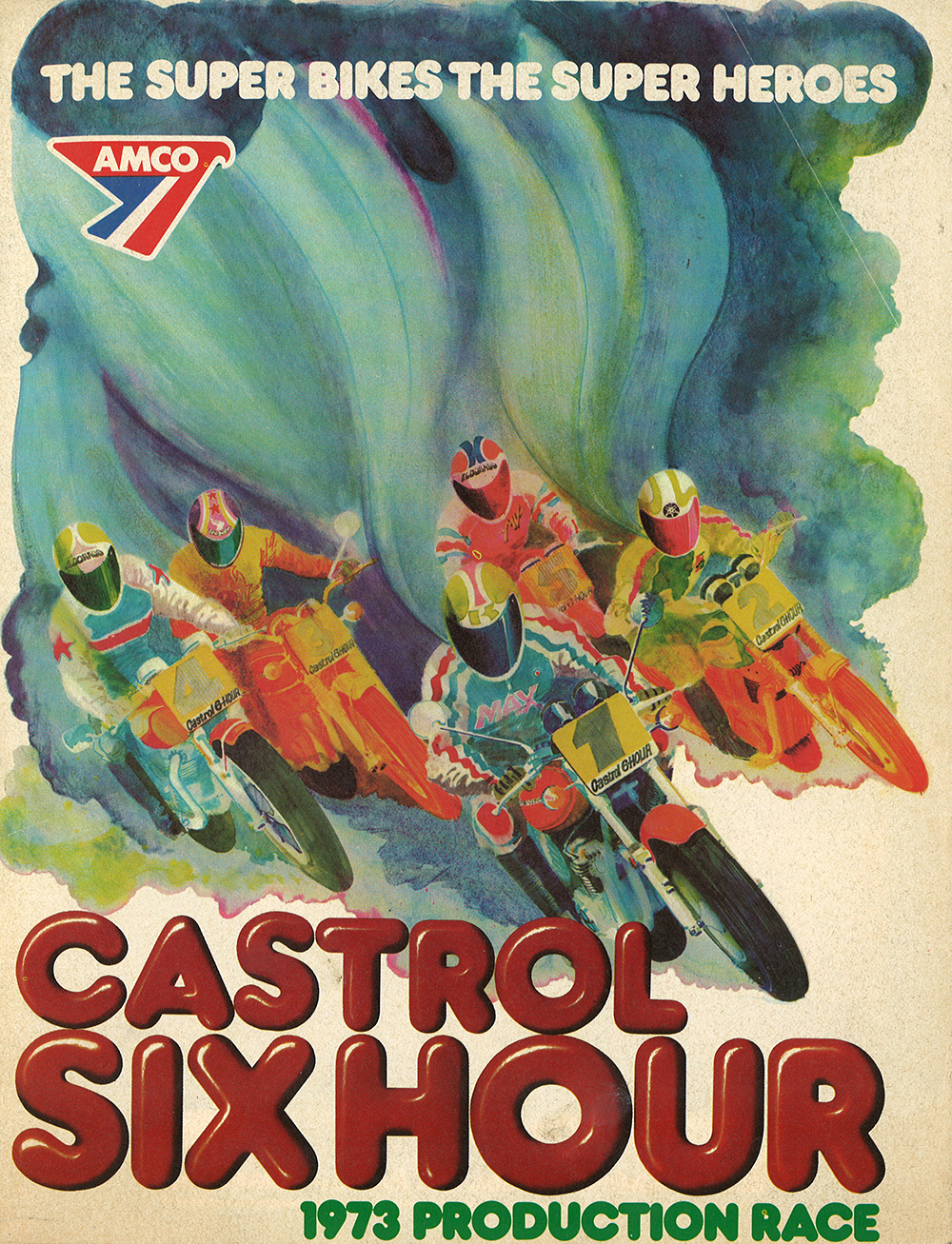

Bryan Hindle leads Gary Thomas in 1974

Bryan Hindle leads Gary Thomas in 1974

With a national television audience and capacity crowds of over 12,000 fans at the Amaroo Park amphitheatre, the Castrol Six Hour became an imperative under the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ edict. However while Aussie auto manufacturers could build such exotica as the Falcon GTHO PhaseIII and Torana SLR5000 A9X for so-called production racing, motorcycle importers were limited to what landed in the crate. By 1973 rumours of race specials built in Japan and shipped to Australia with engine numbers advised by telex, were rife; though never actually substantiated.

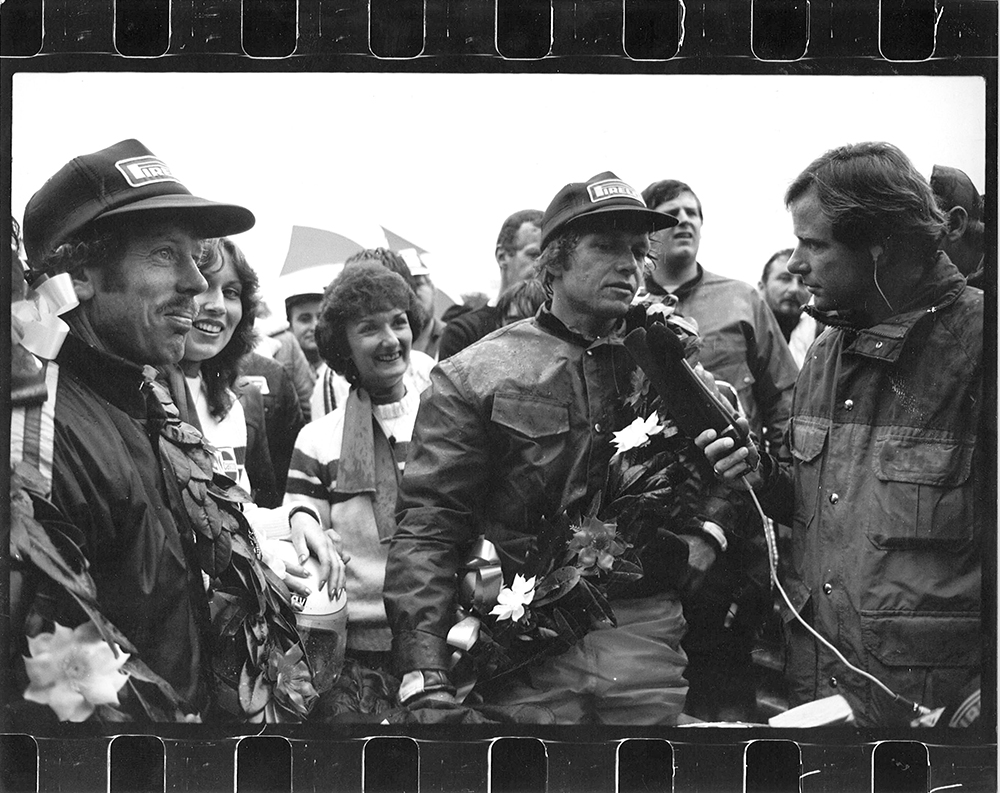

Hindle and Clive Knight are interviewed after the race, before a recount dropped them to second. Then their BMW was DQd for illegal fork spacers

Hindle and Clive Knight are interviewed after the race, before a recount dropped them to second. Then their BMW was DQd for illegal fork spacers

Just what constituted porting and polishing as opposed to ‘dag removal’ could be argued ad infinitum, but a ‘750’ machine stroked and bored to 850cc was a dead giveaway up Bitupave hill. Bespoke front suspension shims, honed gearbox cogs and expanded fuel tanks were harder to detect. As were a mixed bag of ‘production’ parts, hand-picked from different model years. However, with Australian motorcycle sales heading to a high point of over 80,000 in 1974, factory money was available to ensure each ‘production’ motorcycle was as competitive as possible.

“Right from the start, the Willoughby Club was adamant that the success of the Six Hour would depend on its ability to showcase motorcycles you could actually go out and buy,” recalls perennial Race Secretary Vince Tesoriero. “We wanted to show potential customers how the stock bikes performed straight off the showroom floor.

“Scrutineering was very tough and we didn’t make many friends, but it was this integrity that held the attention of riders and TV audiences around Australia.”

Protests started the very second the first chequered flag was waved. The twist grip on the winning Bonneville came off a Yamaha. And two years later it was the remounting of the horn on the winning Suzuki – or maybe it was the jewel-like shine on the piston skirts. Nevertheless, the scrutineers had made their case. And when Ken Blake rode a Kawasaki Z1 900 to a remarkable solo win in 1972 – completing a record 342 laps – not a single transgression was discovered on his bike; or the other 40 finishers. But the deceptions were never-ending. The following year the top three finishers – and the winner of the 250cc division – were disqualified for various indiscretions. And despite ever more stringent and repetitive tear-downs, ‘creative interpretations’ of the ever-expanding supplementary regulations continued.

Although Channel 7 dropped its live coverage, enthusiastic crowds still continued their annual pilgrimage. It was evident everywhere you looked that more money was being spent on preparation. And tyre importers – Dunlop, Metzeler, Continental and Avon – buzzed up and down the pits with the latest product and hands-on assistance. Gone were the B- and C- grade entries that had lived through the event’s infancy. The field was reduced to 40 starters, the smaller capacities banished and the two-strokes appeared doomed. And while it’s doubtful that more than a handful of the riders were actually paid, it was truly an ‘only professionals with a relevant CV need apply’ affair.

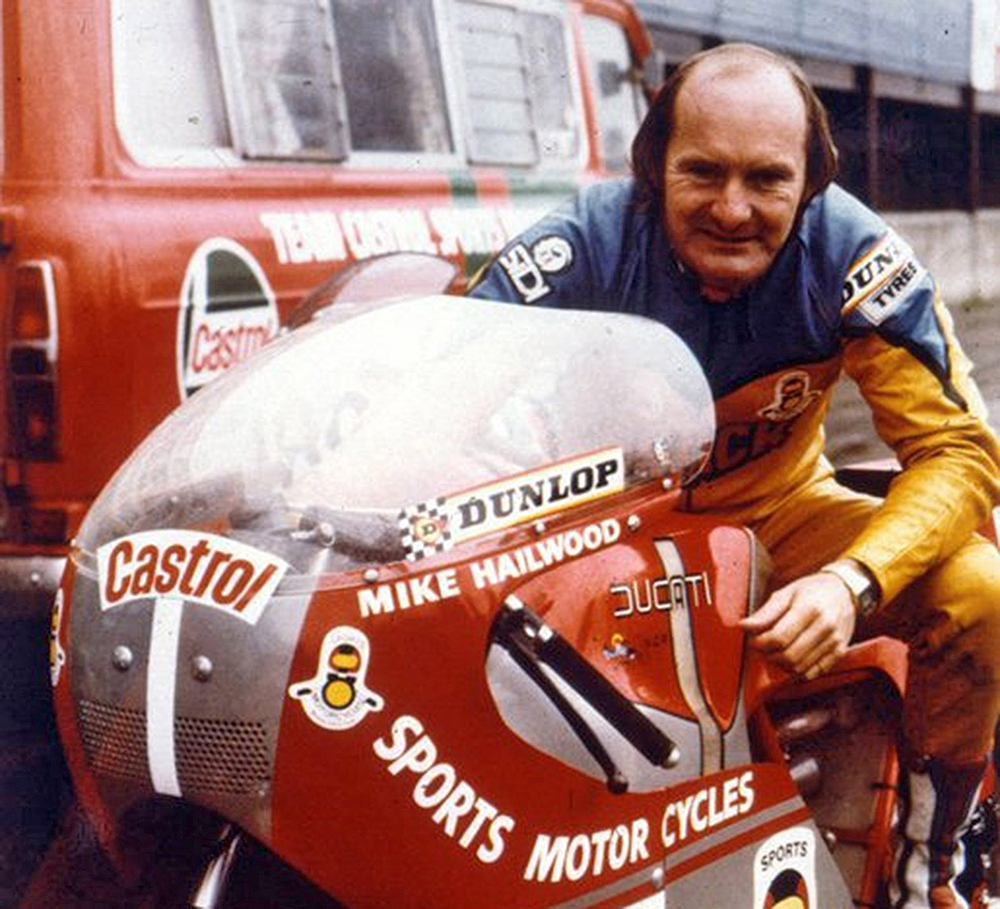

Of course no such credentials were requested when nine-time world champ Mike Hailwood agreed to ride in the 1977 event; partnering his sometime historic racing adversary Jim Scaysbrook on a Ducati 750SS. But Mike the Bike’s proviso was that the campaign would be fun and involve lots of bibulous partying.

Of course sponsorship naturally gravitated to a rider of Hailwood’s stature. Coca-Cola Amatil were about to launch Captain Snack Potato Crisps – Captain Snack being a caped crusader attired in bright yellow with blue trim. The capes had to go, but the sponsorship stuck.

“It wasn’t much, but it covered Mike’s expenses and two sets of yellow leathers,” recalled Scaysbrook. “Frank Matich gave us Bell Helmets and Lindsay Walker the Avon tyres. It wasn’t much at all compared to the serious factory-supported entries. But it was certainly going to be fun.”

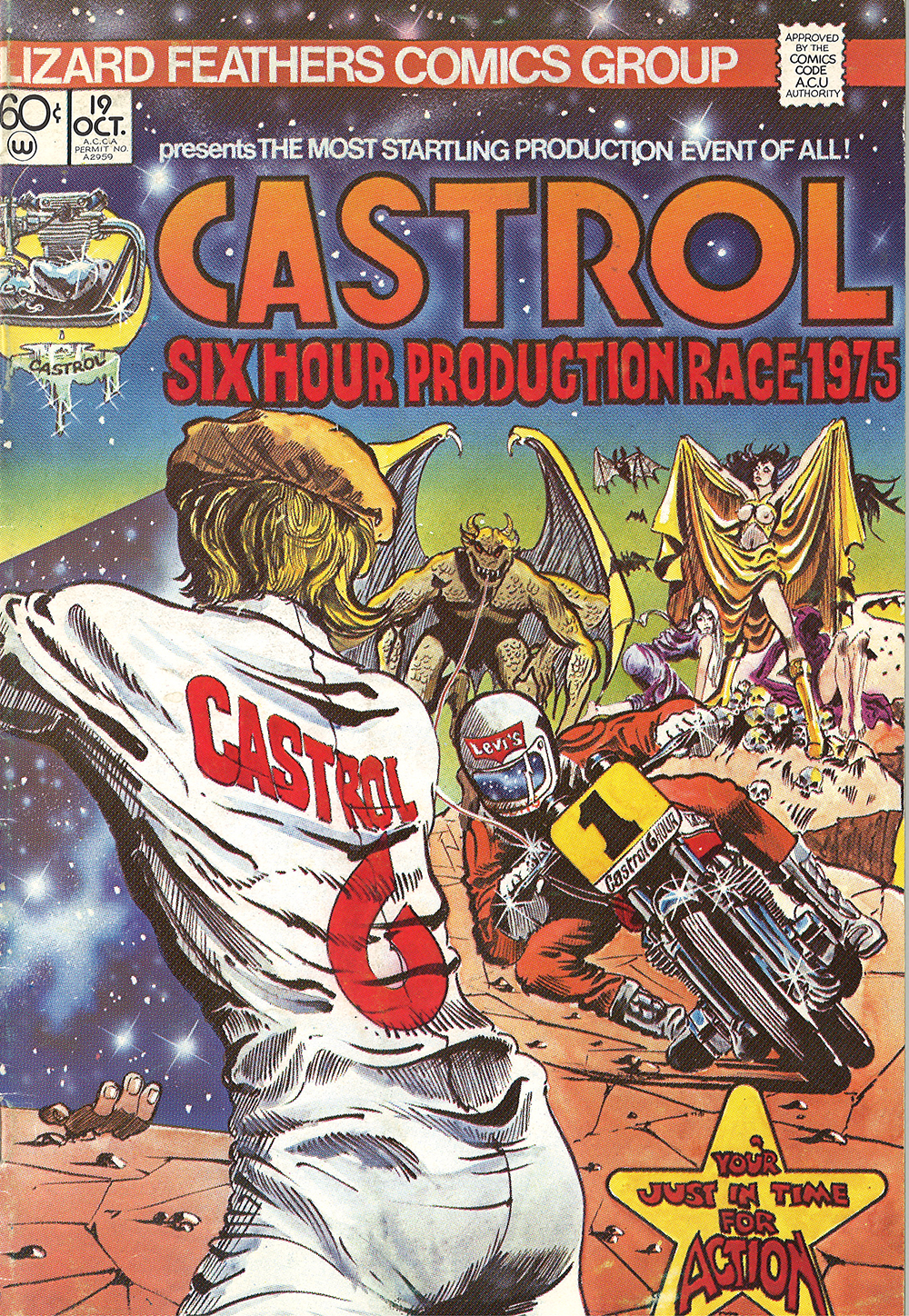

Kawasaki’s 900 played a huge role in the race. Murray Sayle and Gregg Hansford shared the 1975 win…

Kawasaki’s 900 played a huge role in the race. Murray Sayle and Gregg Hansford shared the 1975 win…

Six years later, new motorcycle sales were in free-fall largely due to insurance costs and the popularity of the Castrol Six Hour diminished substantially. Negotiations between the WDMCC and Amaroo Park’s owners broke down and the race was moved from the congenial amphitheatre of Amaroo to the windswept paddocks of Narellan’s Oran Park. And even though the crowd that turned up at Oran was undoubtedly the largest ever for an Australian motorcycle road-race, the atmosphere was never quite the same as the amphitheatre of Amaroo.

… and Roger Heyes/Jim Budd rode to the win in 1976

… and Roger Heyes/Jim Budd rode to the win in 1976

In 1984, the ABC committed to a live telecast of the final three hours of the race, with the proviso that the race presentation finished by 4pm in order to televise the PGA golfing tournament, which meant the coverage of the race was scheduled to finish the moment the leader crossed the line after the clock struck 4pm. This caused disappointment and confusion.

In the final pit stops, the only real contenders – the Richard Scott/Michael Dowson Yamaha RZ500 and the Wayne Gardner/John Pace Honda VF1000R – refuelled and took on new rubber. With a full tank and 90 minutes to the finish, fuel consumption shouldn’t have been an issue. That was until both riders started posting qualifying-like lap times. Pace, having pitted two laps later than Scott potentially had more fuel, but Scott held track position with three laps to run when, at precisely 3:57pm and 10 seconds, he was given the chequered flag on orders from the ABC program director. Scott was most relieved when he spluttered out of fuel on the cool down lap. A bottle of champers was thrust into Scott’s hands as, together with Michael Dowson, he was hauled onto the rostrum… right before the ABC cut to the golf.

The commentators Evan Green and John Smailes were lost for an answer, but briefly filled the airwaves with ‘provisional chatter’. The Honda crew were ropable but sensed a protest was senseless – particularly as the Pace/Gardner machine may not have had the fuel to run past 4pm either. The spectators rode home unaware of the kerfuffle and the TV viewers switched to Wide World of Sport. The love affair had begun to wane.

For almost two decades the WDMCC had controlled the uncontrollable; negotiating TV rights with Channel 7 then the ABC; moving venues from Amaroo to Oran Park; limiting engine capacity when the expensive Suzuki Katana1100 and Honda CB1100R dominated; and tightened licencing requirements, so Sunday riders didn’t bring down the likes of Wayne Gardner, Kevin Magee or Mick Doohan.

In February 1988 the WDMCC called it quits. And Castrol’s press release said it all.

“The Six Hour was born in an era when bikes sold over the counter were, in many instances, suspect. So what better than a long-distance race in which they could prove their worth.”

What Castrol didn’t say was that motorcycle sales had again hit an annual low of less than 19,000, forcing the closure of many motorcycle shops. Or that World Superbike racing was booming – and was here to stay. True Production Bike racing would be limited to the smaller capacities which still thrive as economical feeder series for our homegrown ASBK championship.