With six Isle of Man TT victories and 22 Grand Prix/TT wins in Europe, Scotland’s Jimmie Guthrie was one of Britain’s best racers. Four of his victories, including a 350/500 double at Berne’s Bremgarten circuit in 1937, were in events designated European Grand Prix – the one-meeting European title of the day.

At his peak in 1935-’37, Guthrie won 18 races from 27 starts, including three successive European 500 GPs at Clady (Belfast), Hohenstein-Ernstthal (later named the Sachsenring) and Berne. He’d have made more GP starts, but the Norton team did not contest the French and Italian classics.

He won a total of 74 races, including the North West 200 in Northern Ireland four times in a row, and in 1934-36 set numerous world speed records at France’s Linas-Montlhéry circuit, with a best speed on a Norton 500 of 117.44mph.

Guthrie was 90 seconds ahead just 2km from the finish in the 1937 German 500 GP at Sachsenring when he crashed, through no fault of his own. It would have been his third successive 500 GP victory at the circuit, third successive 500 GP victory in the summer of 1937 and fifth victory of the season.

The Scot struck a tree, sustaining multiple limb fractures and a fractured skull, and died a few hours later in a Chemnitz hospital. He was 40 years old and was said to be planning retirement at the end of the season.

Guthrie left a wife, Isabel, daughter Margaret and a son on the way. Jimmie Guthrie Jnr won the 1967 Manx 500 GP on a Norton. Isabel Guthrie lived into the 1990s and in her senior years would still drive her small car solo from Scotland to south-west England to visit her daughter.

No report on the cause of the crash was filed with the then governing body, the FICM, and various hypotheses have been advanced… a broken rear axle, failure of an axle-retaining lug or interference from another rider who was one lap behind. Two names have been advanced concerning that theory. A broken connecting rod was another idea put forward and it was even suggested he was shot!

Photographs of Guthrie’s crashed machine show it missing its rear wheel.

Guthrie is not forgotten, thanks to the imposing Guthrie Memorial on the IoM Mountain course. There is also a bronze statute in his home town of Hawick (pronounced ‘Hoik’) and a memorial stone on the former Sachsenring public-road circuit.

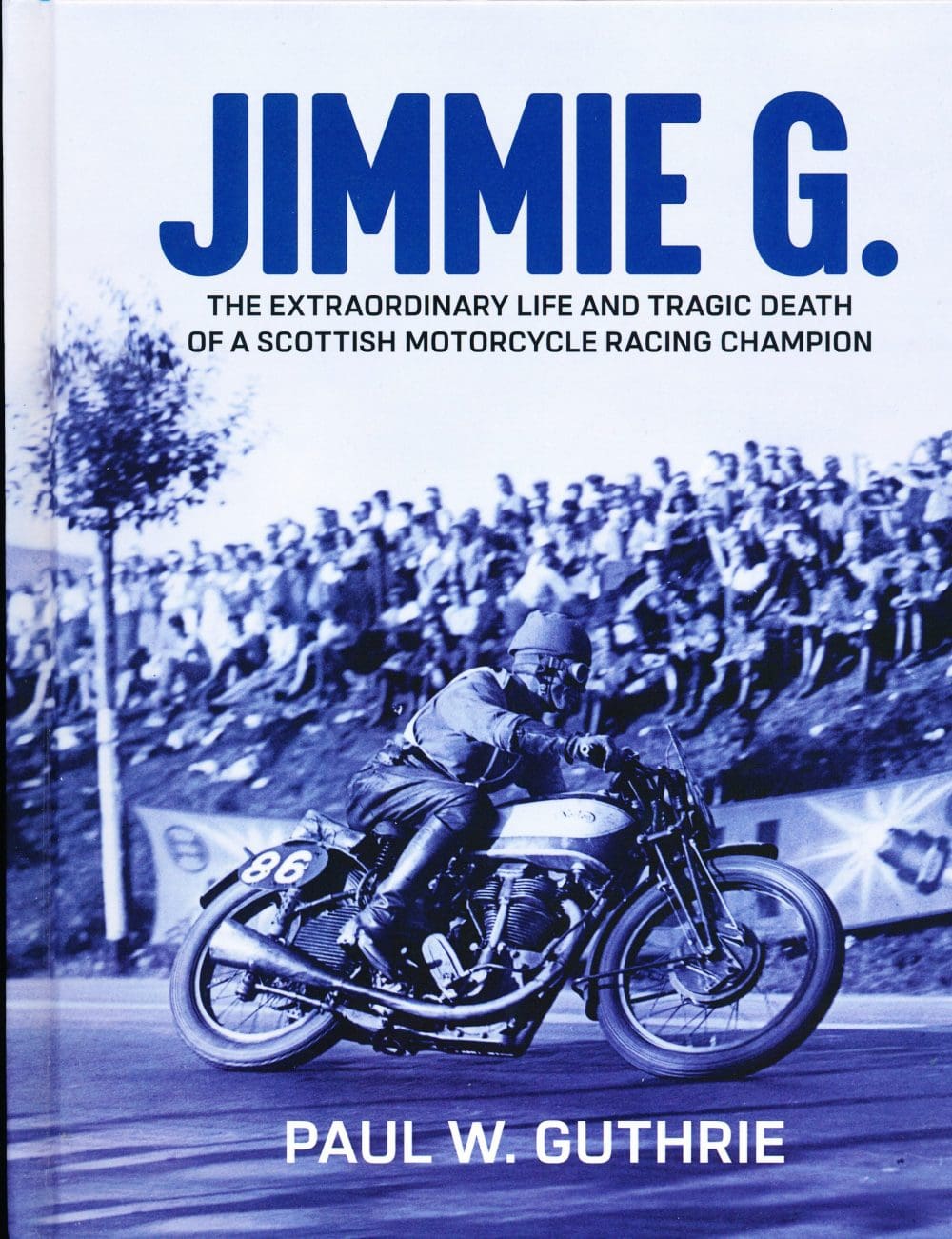

We now know much more about Guthrie thanks to a forensically researched new book Jimmie G, written and published by the unrelated Paul W Guthrie.

Paul Guthrie had his interest sparked when his father showed him magazine stories and the shared surname. He was a motorcycle mechanic in rural Australia, but switched to engineering and in 1999 moved to Germany, putting him within better reach of research opportunities in Germany and the UK. He also found a 1997 book published by the Hawick Archaeological Society, Jimmie Guthrie – Hawick’s Racing Legend, by Gordon Small.

Paul has used this access well, providing extensive background on Norton and its racing efforts, and 25 pages on how German motorsport was run from 1933 onwards under Adolph Hitler. These were dark times. It’s been revealed elsewhere, but several British Continental Circus racers, including Fergus Anderson and Ted Mellors, were listed in the so-called Gestapo Black Book of people who would be rounded up if Britain was invaded.

The sections on Norton and the German factory teams include some very candid assessments of the various team personalities, machine performance and the teams themselves.

Guthrie’s was an amazing story throughout, beginning his working life as an engineering apprentice. In 1915, while in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, he was at Gallipoli. The Borderers suffered catastrophic losses there, with only 200 men surviving from a battalion of nearly 1000.

He then served in Egypt, where he was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps. In 18 months he was involved in 13 battles and then, with the Royal Engineers, was a sapper in France and perhaps a dispatch rider.

Jimmie Guthrie made it home to Hawick in 1919, where with brother Archie he founded an automotive engineering business that doubled as an agent for AJS, Dunelt and Enfield motorcycles. He started competing in reliability trials and hillclimbs in 1921 and made his TT debut in 1923.

Remarkably, Guthrie did not enjoy high-profile success until he was 30, finishing second in the 1927 IoM 500 TT on a New Hudson. He rode for Norton in 1928 but missed much of the 1929 season after crashing during official IoM practice and sustaining some spinal injuries.

He joined AJS in 1930 and at age 33 recorded his first major victories in the IoM 250 TT and German 350 GP at the Nürburgring. He returned to Norton in 1931, but his career did not truly blossom until 1934, with a victory double at the Isle of Man and his second successive double in the Spanish TT at Bilbao.

So what really happened to Jimmie Guthrie? The author examines the evidence on mechanical breakage and rider interference theories in great detail, as well as discussing the delay in transporting Guthrie to hospital and the lack of an official report on the crash. His conclusion may well surprise readers.