Words & pics: Ben Purvis

Between 1986 and 1991, the Japanese economy went through an unprecedented boom and the motorcycles created in the era reflected its buoyant mood and ready cash-flow with an immense rate of technological development.

It was a period that saw the development of spectacular two-stroke 250 race replicas, jewel-like 250cc and 400cc four-stroke fours and legendary machines like the Honda RC30, Fireblade and VFR750, not to mention the oval-pistoned NR750.

That era peaked 30 years ago in 1989 and by 1991 Japan’s economy was crashing, bringing the most fertile time we’ve ever seen in motorcycle development to a sudden halt, as the country slumped into a period of economic stagnation that would last 20 years. But what might have happened if there had been a few different decisions from the economic policymakers and the Japanese boom had continued a few more years?

We can actually get a glimpse at what might have been thanks to the way the internet now opens the doors to the world’s patent offices, allowing anyone to rummage through documents that would have been tucked away in IP libraries back when they were new. By searching through the documents filed by Japan’s motorcycle firms – and most notably the leading pair of Honda and Yamaha – during the 1986-1991 bubble, it’s possible to see some of the ambitious projects that were ditched once the money stopped flowing so freely.

While these are by no means the only motorcycle projects that were under development during Japan’s economic bubble, the ones we’ve picked here show the sheer scope and imagination that was being encouraged at the time. We’ll never know whether any of them would have been Fireblade-like successes or NR750-style deadends, but it would have been fascinating to find out…

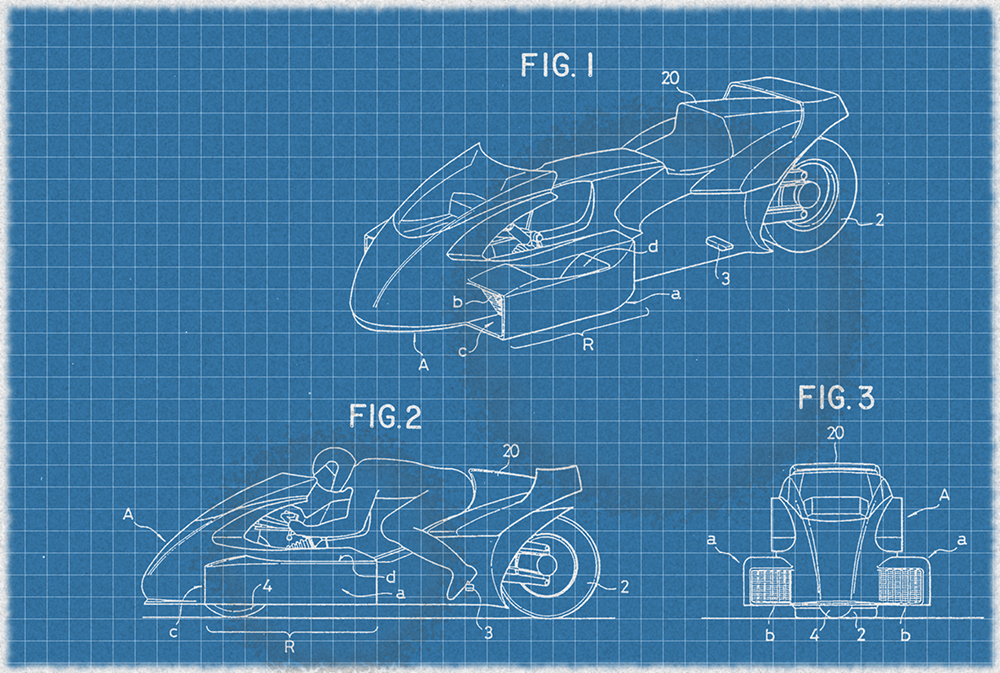

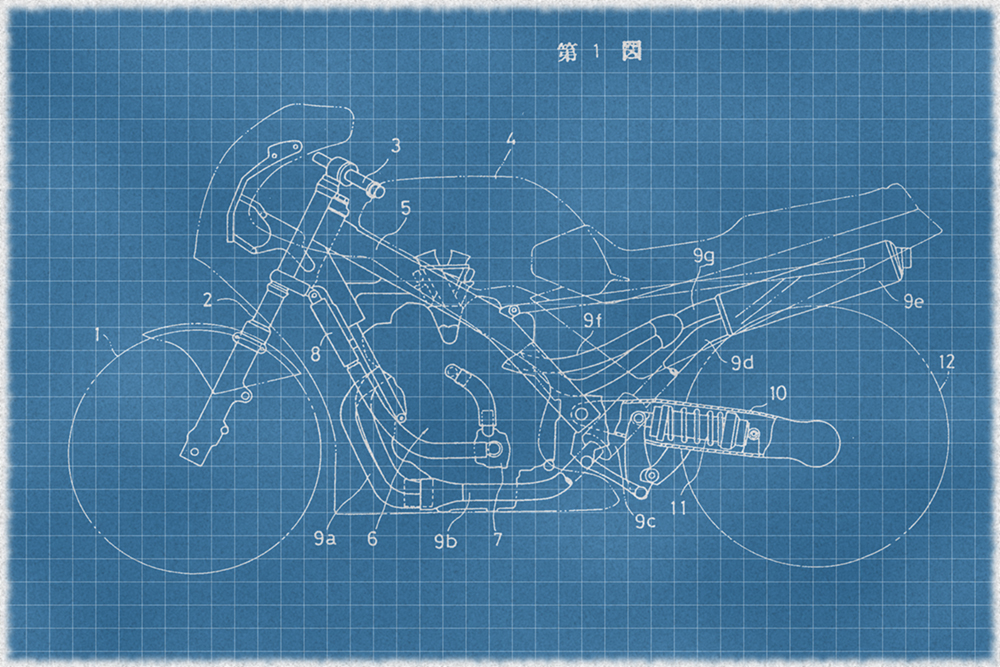

Honda’s ground-effects bike

Winglets have been the subject of a development war in MotoGP for the last few years and are a defining theme of several new 2020 road bikes – not least Honda’s CBR1000RR-R Fireblade. But more than 30 years ago, the firm had much more ambitious plans to add downforce to its bikes.

This 1987 project came from the pen of Satoru Horiike, who’d later design the 1999 CBR600F and go on to run HRC during the dominant era of the RC211V. While conventional bikes struggle to make downforce as they lean around corners, this idea revolves around keeping a large proportion of the bike parallel to the road at all times. The bodywork, rear wheel and engine all remain upright, along with components like the radiators that are mounted in the car-style side-pods, while a pivot in the middle of the chassis means the rider, fuel tank, front wheel and bars all lean into corners.

The design not only means that bike’s aerodynamics can be used to create significant downforce, using the phenomenon of ground-effects thanks to venturis under the side-pods, but the rear tyre can be a wide, car-style design with squared-off shoulders and a much larger contact patch than any motorcycle rubber could hope for. A separate rear wing helps push it down onto the ground.

While racing rules around all-enveloping fairings would make this design illegal in MotoGP, we can only speculate as to how fast it might have been able to take corners.

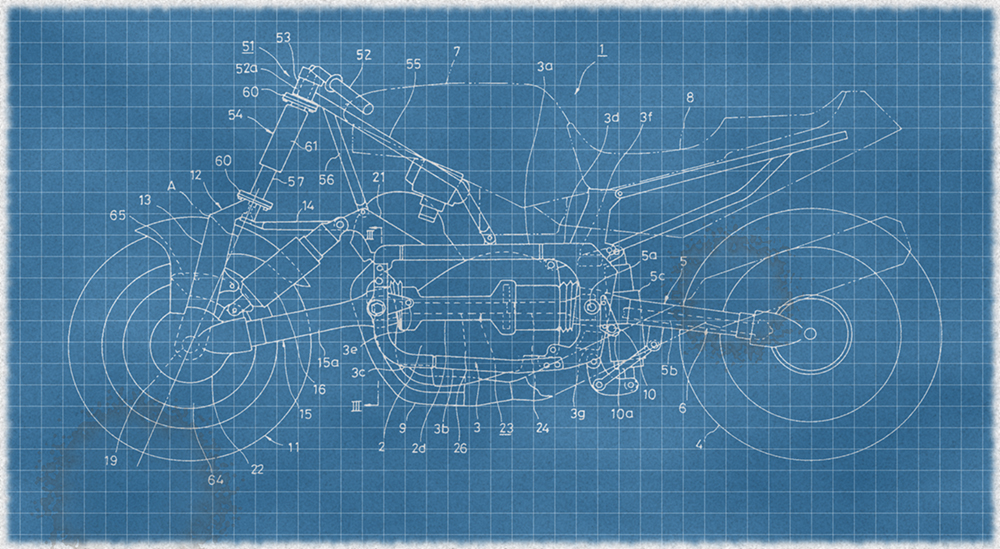

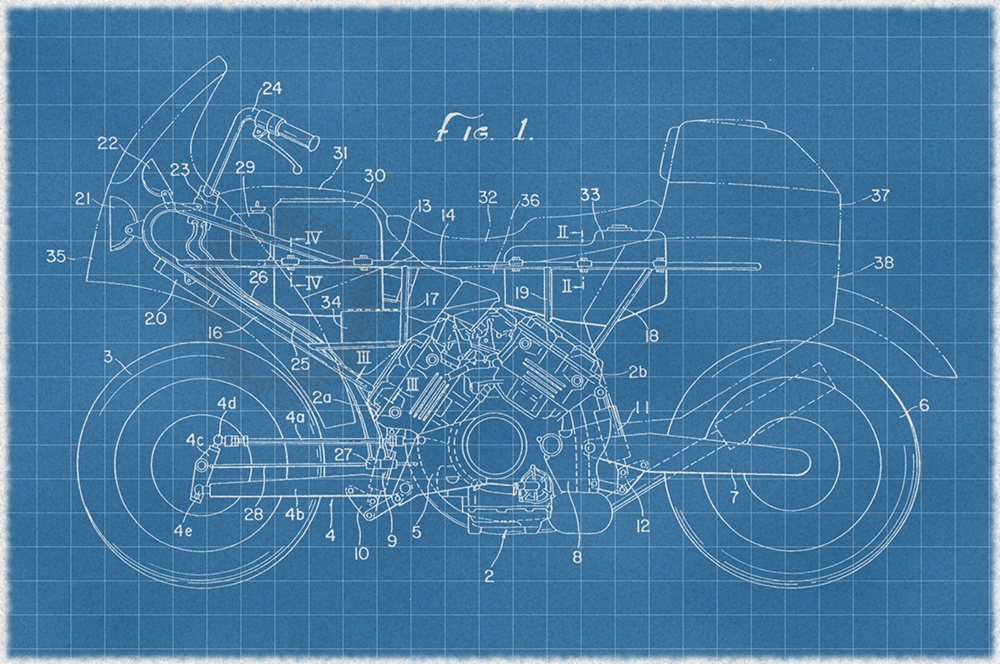

Two-wheel-drive Yamaha GTS1000

Yamaha’s GTS1000 might not have hit the market until 1993 but the project for a hub-centre-steered sportsbike had already been underway for years. Back in 1989 the Morpho concept bike previewed the idea of a single-sided front swingarm and the company had been working on a derivative of James Parker’s RADD design for several years even then. But this patent shows the hidden advantage of the layout that would never be seen in a production model – the ease of converting the design to two-wheel-drive.

Normally, two-wheel-drive bikes stumble at the same problem; how to drive the front wheel without limiting suspension or steering movement. But a front swingarm largely solves the issue, as it’s able to act as a shaft carrier. On this design both the front and rear wheels are shaft-driven from the same output on the side of the transmission, with one shaft running forwards, the other to the rear wheel.

Like the real GTS1000, the bike uses a transverse four-cylinder engine and Parker-style front suspension. The front wheel is deeply dished to allow a universal joint to be fitted in its centre, with the pivots right on the steering axis, taking drive from the bevel gears that turn the front shaft’s output 90 degrees.

This design came at a time when Yamaha was starting to focus quite hard on two-wheel-drive, an ambition it would pursue through the 90s and well into the 2000s, albeit later turning to conventional suspension and an Öhlins-developed fluid-drive system to take power to the front wheel.

More recently electronic traction control technology has pushed the idea of two-wheel-drive to one side, although it may yet have a revival once electric bikes are more commonplace.

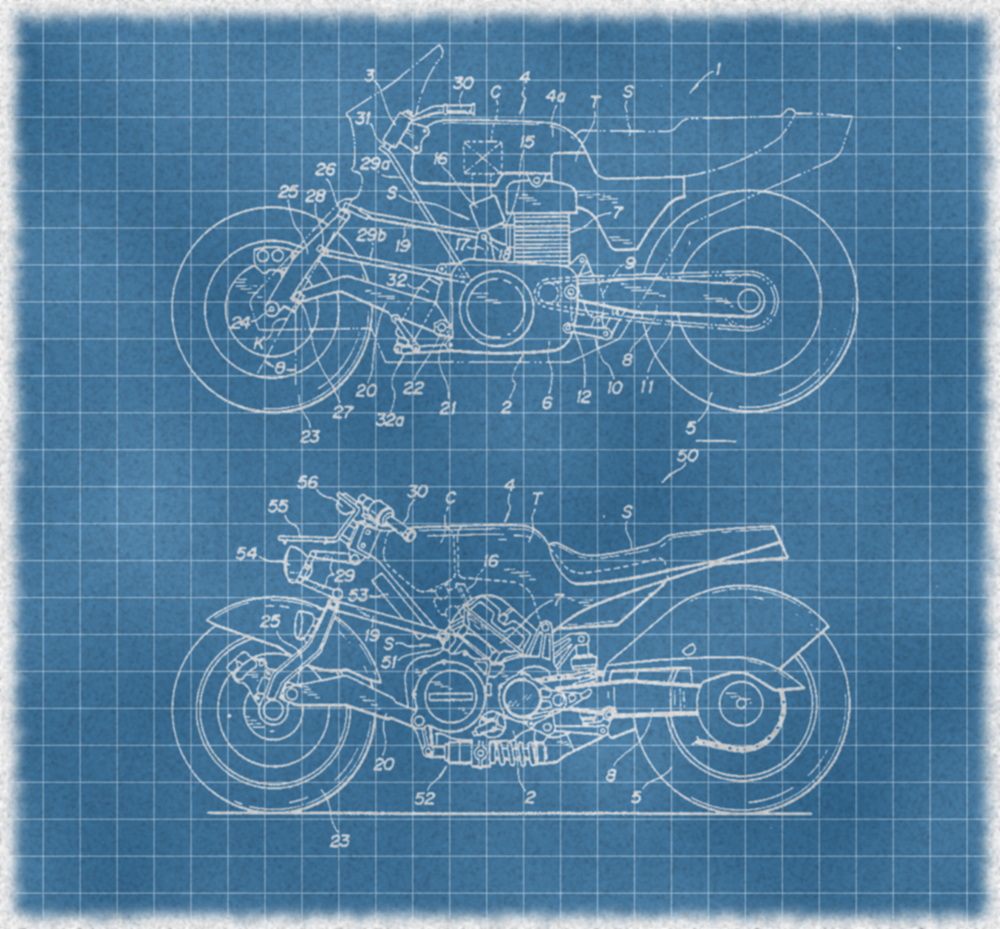

Front-wheel-drive, rear-wheel-steer Honda

Satoru Horiike was at the forefront of Honda’s wild ideas in the bubble era and this 1988 design again shows how prepared he was to throw out all preconceptions in an attempt to create a better motorcycle.

If your brain is screaming that this bike looks ‘wrong’, that’s understandable. Everything familiar has been flipped around, with drive going to the front wheel and steering to the rear. Just to throw another curveball into the mix, Horiike has again employed the mid-chassis pivot that he suggested in his previous patent. As a result the engine and front wheel don’t lean in corners, while the rest of the frame including the bodywork, bars and rider’s seat all tilt like a conventional bike.

That means the design can feature a steamroller-style front wheel fitted with a wide, square-shouldered, car-style front wheel, since it doesn’t have to lean. And with no steering on the front wheel there’s no complexity in its drive system or suspension – a perfectly normal swingarm and chain is all it takes. Of course, there is a bit more of a struggle at the back when it comes to getting steering and suspension on the rear wheel.

The solution is something that looks a lot like a normal steering head, but with shopping trolley-style trail and a trailing-link suspension system.

The steering itself is a hydraulic system, with hydraulic cylinders translating movement at the bars to movement at the rear wheel, although a second version of the design features a mechanical setup using rods and switches the angled steering head for a vertical one.

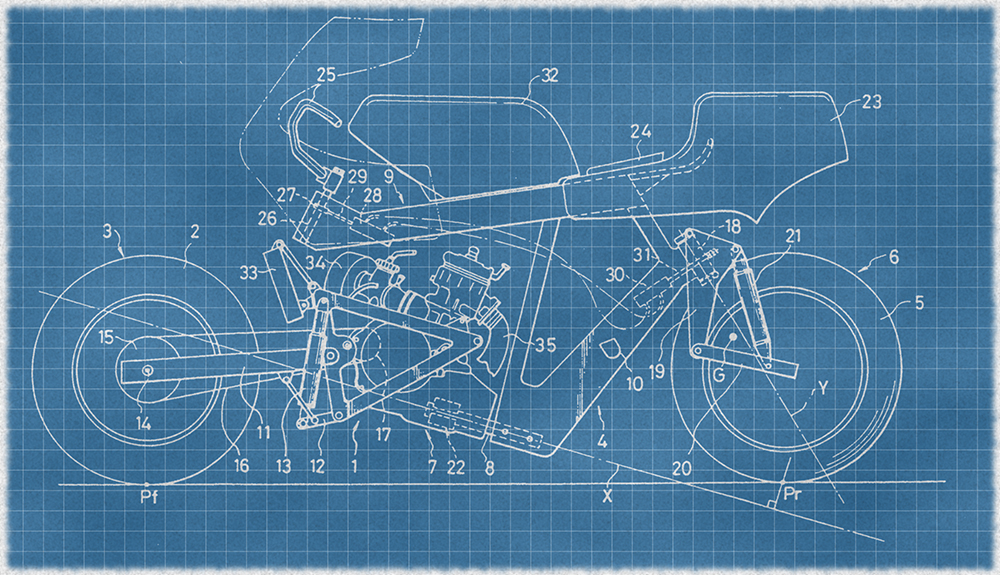

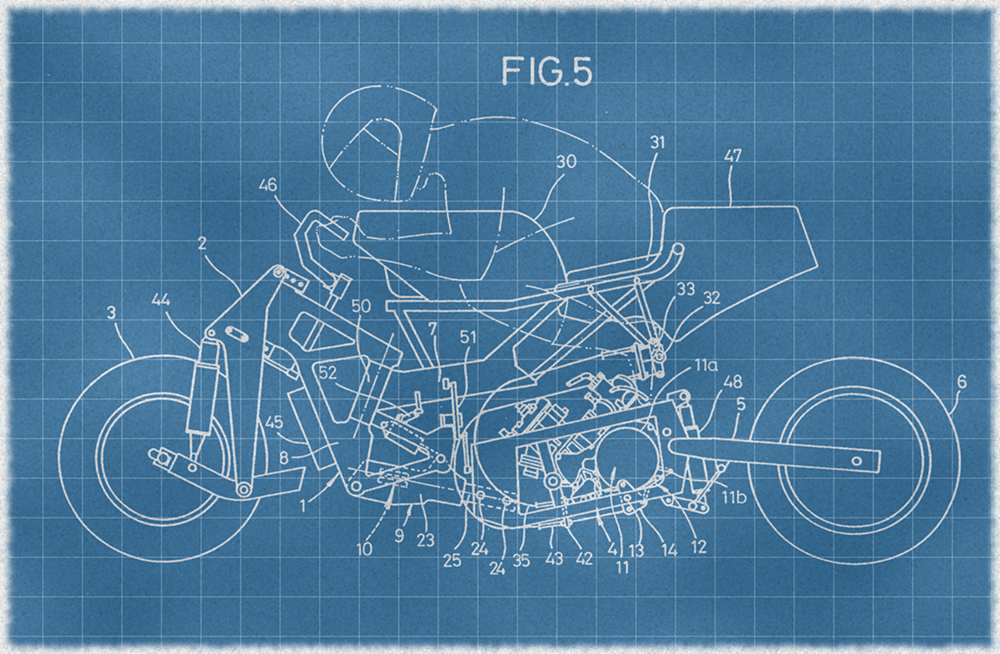

Honda’s V6 superbike

Dating back to the tail end of the bubble era, Honda’s 1990 patent for a V6-powered superbike shows what might have replaced the RC30 as the firm’s WSBK weapon if the 1980s development arc had continued unfettered.

Unlike a lot of the bikes here, this one doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel, but it does show one significant departure in the form of its V6 engine. Featuring a narrow angle between the cylinders, it’s a relatively compact design with a layout that looks surprisingly similar to the 990cc V5 that would appear more than a decade later in the dominant RC211V MotoGP bike. Some sources claim that the RC211V’s engine was derived from an earlier WSBK-aimed V6 prototype; if that’s true, then this is likely to be that bike.

Engine aside, the patent shows an intriguing solution to the ever-present problem that V-shaped engines pose – how to package the rear cylinders’ exhaust pipes without impinging on the space needed for the rear shock and its upper mounting point.

To get around the issue, Honda has put the spring and damper inside the swingarm, with a rising-rate linkage to compress it when the rear wheel moves upwards.

In fact, the V6 bike’s suspension is very similar to the Unit Pro-Link design that eventually debuted on the RC211V early in the current millennium. While the GP bike’s shock is mounted vertically rather than horizontally, it also had the upper shock mount on the swingarm itself rather than the frame, and a very similar linkage arrangement.

Of course, when the Japanese economy collapsed shortly after this patent was penned, any chance of the V6 design reaching production disappeared with it. And given how Honda struggled to sell the oval-pistoned NR750 a couple of years later, it’s clear that while the V6 would be a classic now if it had reached production, it would probably have flopped when new.

Hub-steered Honda V4s

It wasn’t just Yamaha that was obsessed with alternative suspension and steering systems in the bubble era – Honda might not have ever made a production hub-steered model but it was a field that it explored extensively at that time.

This machine comes from a patent that was published in 1987 but penned two years earlier in 1985, just as the Japanese economic boom was getting underway. It’s one of at least three concurrent designs from the same period that Honda was working on, all with their own variations of hub-centre steering and the firm’s signature V4 engine layout.

At this stage, it’s clear that Honda was intrigued by the packaging options that a hub-centre steering system provided. Having accepted that any such design means using an indirect linkage between the bars and the front wheel, Honda realised that it was no longer limited as to where the bars were fitted. That meant it was free to try radically shifting the position of the rider and thus the bike’s weight distribution.

In the bike shown here, the weight is moved far forward compared to a conventional design, centralising the rider’s mass directly above that of the engine. In terms of proportions, the result was far from beautiful, with a bluff front fairing parallel to the leading edge of the front tyre. Other variations on the theme saw the masses moved similarly far backwards, but it seems that during this period there was a strong faction within Honda that was convinced that the telescopic fork’s day was over and the future lay in the adaptability that hub-centre-steering offered.

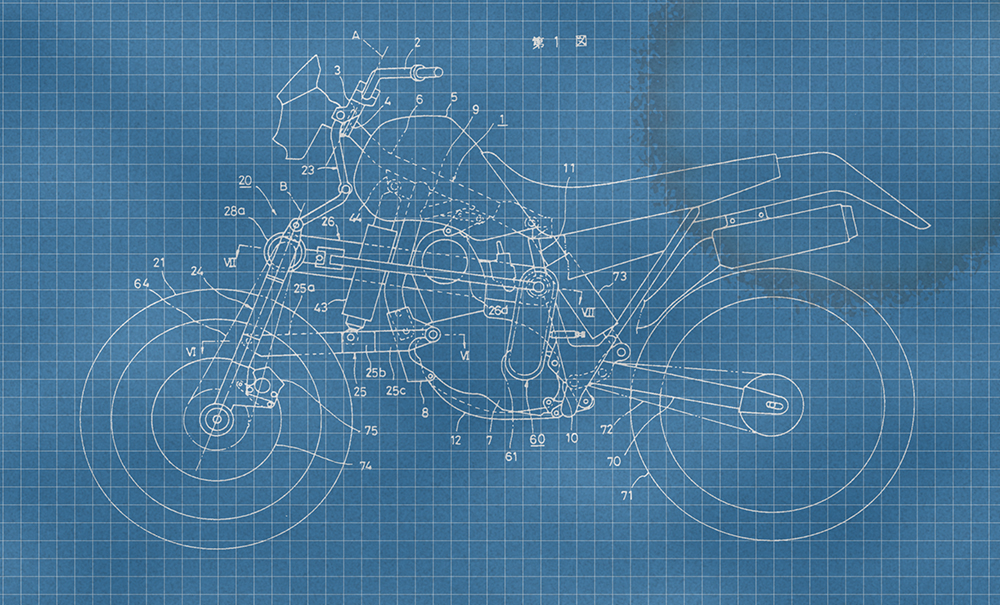

Hinged-framed Honda

The ideal combination of frame flexibility and rigidity is one of the motorcycle designer’s holy grails, but this idea – yet again from the pen of HRC boss-to-be Satoru Horiike – adds a mind-boggling combination of hinges and pivots into a sports bike’s chassis as part of his late-80s efforts to reinvent the motorcycle.

Shown in a patent dating from 1988, this is a variation of some of the ideas he pondered in the ground-effect and front-wheel-drive ideas that he was working on at the same time.

The design has two key elements that set it aside from anything we’d normally see on a superbike. First, the frame pivots in its centre so the rear section – including the engine, swingarm and rear wheel – remains upright at all times. As on Horiike’s front-drive proposal, that means the rear wheel can be a wide, car-style design with a massive contact patch.

Up front there’s a leading-link suspension system that’s unusual in itself, mounted on a half-frame that does lean into corners, along with the bike’s bodywork, the bars and the rider.

But the strangest element of all is that the rider’s seat section, including the fuel tank and tail, is mounted on another hinge. That means when the bike’s front end leans over, the tank, seat, tail and rider swing inwards, towards the corner, to shift the weight distribution sideways. In effect, the bike’s design means there’s no need to hang off on the inside when cornering as the weight swings that way on its own.

Whether such a design could ever feel natural to ride remains a moot point, since there’s no evidence that it went any further than these drawings, but it seems a shame that nobody today appears to be trying such radical methods to make huge leaps forward in bike design.

Reverse-engined Hondas

Another bubble-era design that shows the out-of-the-box thinking that Honda’s designers were being encouraged to adopt at the time, this design shows elements that actually have come to fruition since then.

Although part the firm’s brief effort to move to hub-centre steering and front swingarms instead of forks, the resulting layout includes an idea that’s used today on the firm’s Moto3 racebikes.

The front suspension system seen here is remarkably similar to James Parker’s RADD layout from the same era, which eventually led to Yamaha’s GTS1000. However, the GTS made an essential error in making the upper front suspension link shorter than the lower one – something that Parker’s own earlier designs avoided, and which he blames for the Yamaha’s heavy, dead steering.

Although this 1986 patent is far earlier than the Yamaha GTS, it seems Honda reached the same conclusion as Parker, that the upper front suspension link needed to be long. But to achieve that, the firm took the radical step of rethinking its engine layout to accommodate that long upper front suspension link.

Two takes on the idea are shown in the patent. One takes a conventional engine (a parallel twin in this case) and tilts the cylinders backwards while reversing the cylinder head so the intake is at the front and the exhaust at the rear. Honda’s current Moto3 bike’s single-cylinder engine does exactly the same thing, as does BMW’s G 310 and Yamaha’s WR motors.

The second, more radical solution proposed in Honda’s patent is to reverse the engine entirely while keeping the cylinders vertical. That means it puts the transmission in front of the cylinders to clear space ahead of the motor and make room for the front suspension linkage.

Yamaha hub-centre-steered, Two-wheel-drive off-roader

It’s clear that during the mid-to-late 1980s, there was an absolute conviction among bike designers that hub-centre-steering was the future and conventional forks were an anachronism – virtually every one of the wild designs that emerged during that period included some form of front swingarm. Bear in mind that such designs were even being used in GP racing at the time, notably by Elf, and it’s easy to see how that conclusion was reached.

On this Yamaha design from 1990 the firm has made the move to hub-centre steering so it could adopt a chain and shaft-driven front-wheel-drive system on an off-road style machine.

You can clearly see that the engine and rear end of the bike are perfectly conventional, but the design strays far from anything normal at the front.

A second drive chain runs up from the front sprocket to a bevel gear that converts the drive to a shaft that goes to the front of the bike. That shaft doubles as an upper front suspension linkage, and features another bevel gear to drive a chain that runs down the left hand ‘fork’ leg to power the front wheel. Steering is via a linkage that connects the bars to the right hand fork.

On another variation shown in the patent, there’s a third chain instead of the shaft taking power to the front, eliminating the need for bevel gears.

It’s understandable that such a convoluted method of getting two wheel drive didn’t reach production, but it’s worth noting that Suzuki’s 1991 XF5 concept bike used a vaguely similar arrangement, albeit with a shaft running down the forks rather than hub-steering, and the XF4 ‘Ugly Duck’ concept shown at the same time had an even more complicated arrangement of multiple chains and leading-link suspension to achieve front wheel drive.