Massimo Tamburini was the progettista (designer) par excellence. He led the pack that defined the motorcycles we ride today. Those who followed his lead in shaping the evolution of two-wheeled design – and have continued to do so since he left us on

6 April 2014, at the age of 70 – include Miguel Angel Galluzzi, Pierre Terblanche, Gerald Kiska, Adrian Morton, John Mockett and Tim Prentice. There are many others – a younger generation following Tamburini’s tyre-tracks.

In creating the likes of the Bimota SB2, Ducati 916 and MV Agusta F4, he established the benchmarks by which later designs were to be measured.

In addition, these models delivered performance that lived up to the expectations aroused by their looks. Massimo Tamburini was a genius: I’m proud to say he was also my friend. Born 50km inland from the Adriatic coast resort in November 1943, he was passionate about motorcycles from an early age – the need for mobility in a war-ravaged country made bikes king in Italy until 1955’s Fiat Nuova 500. He’d hoped to go to university to study mechanical engineering but his farming parents couldn’t afford it, so he ended up at the local technical college where, among other things, he learned how to weld and the fundamentals of design.

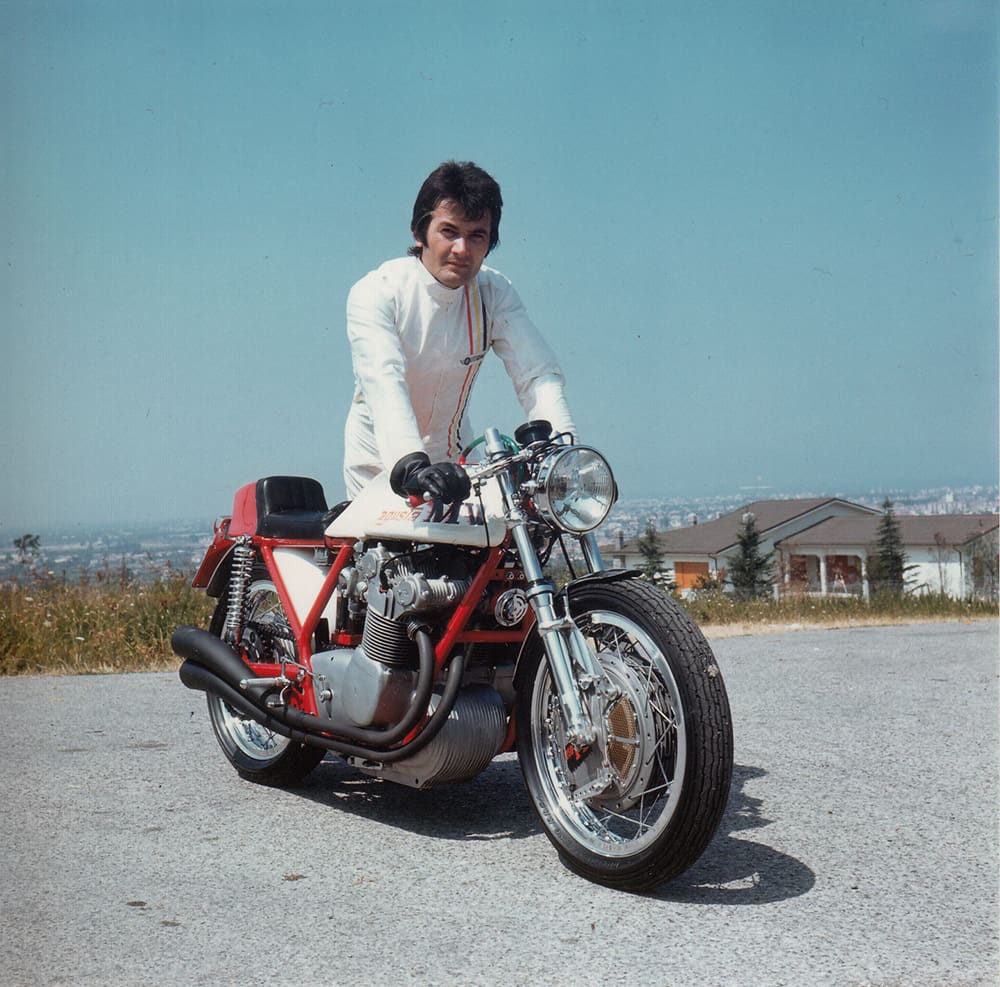

He then teamed up with two other young locals in 1965 to start a business manufacturing ducts for the air-conditioning systems being installed all over Italy as part of the post-war economic boom. Reflecting the first two letters of its founders’ surnames – Bianchi, Morri and Tamburini – they named the company Bimota. Massimo was a big fan of the 250cc four-cylinder GP racers built by Benelli and dreamed of such a bike for himself – but Benelli didn’t make fours to sell to customers. So in 1970 he bought a crashed example of the only four-cylinder Italian motorcycle then available – MV Agusta’s plug-ugly 600cc shaft-drive sports tourer.

He stripped the engine and converted it to 750cc, fitted chain final drive, then built a conventional but good-looking chassis to house it, working after hours by himself in a corner of the Bimota workshop. Fitted with cutting-edge Italian hardware of the era, such as Ceriani forks and massive Fontana drum brakes, it was the first Tamburini-built motorcycle, the start of an era.

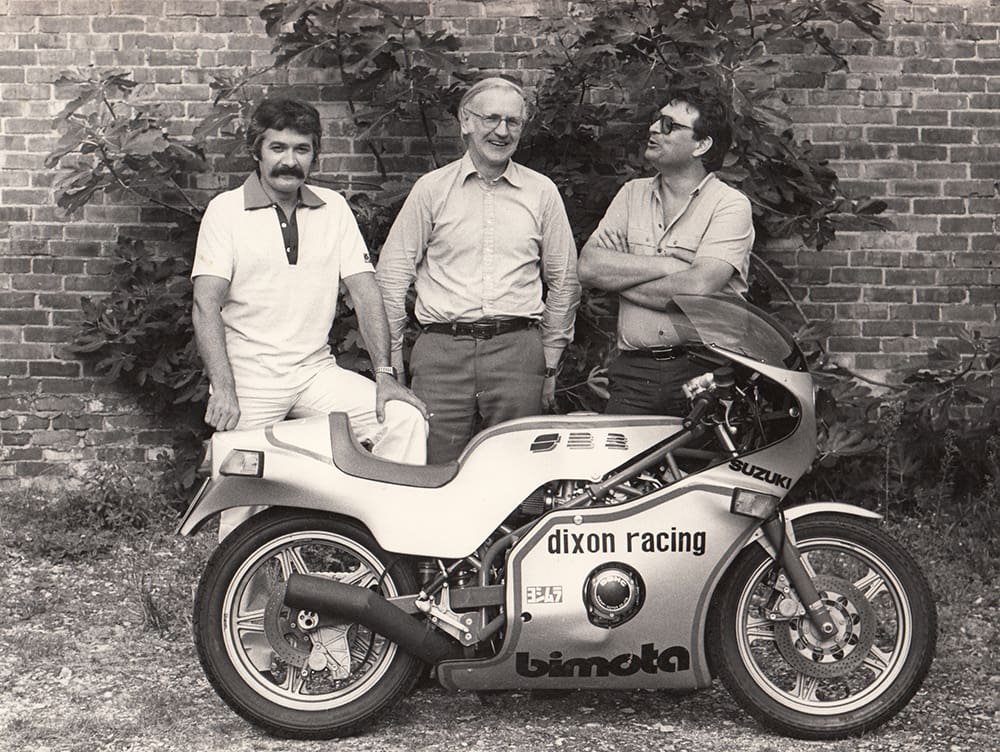

Fired by favourable comments aroused by his MV’s improved handling, Massimo became intent on building a Honda CB750-engined racer that would be the genesis of a company building such bikes for customer sale. Equally bike-mad, Giuseppe Morri was eager to run the bike business while Massimo built the products, so the two split from Valerio Bianchi in 1973 but retained the Bimota name in new career constructing

specialist motorcycle frames.

To begin with, the duo focused on constructing race chassis for engines as diverse as the four-stroke 500 Paton twin (the first GP Bimota, raced by Roberto Gallina in the 1974 season), the V4 Paton two-stroke, the 250 Morbidelli twin that went on to win the world title in 1977, and – most successfully – the TZ250/350 Yamahas. But although Tamburini and Morri had the satisfaction of knowing their Bimota frames had earned half a dozen world championships, that wasn’t the same as doing so under Bimota’s own name.

So they registered the company as a manufacturer with the FIM and were rewarded with Bimota’s first official world title in 1980, after South African privateer Jon Ekerold defeated the factory Kawasaki team to win the 350cc crown on his Yamaha-powered Bimota YB3, with its sweet-handling Tamburini-designed chassis.

Tamburini’s Bimota-era trademark was a tubular steel frame with the swingarm pivot mounted coaxially with the gearbox sprocket. This ensured constant chain tension at a time when chain technology was struggling to keep pace with engine torque outputs, and he improved traction via longer swingarms. Tamburini also pioneered the use of monoshock rear suspension: it was on the 1976 HDB1 500cc twin-cylinder GP racer, and in 1977 made it to the street model 750cc SB2 – the HB1, like the MV, had been a twin-shocker. He also helped create the Ducati-powered DB1, which debuted in 1985 with similar integrated styling.

Tamburini then went on to join Cagiva, a thriving company (owned by two wealthy road-racing tifosi, Claudio and Gianfranco Castiglioni) which purchased the ailing Ducati firm in 1985. Tamburini ended up spending 25 years with the company.

First up for the design genius was the Ducati Paso 750 desmo V-twin sportsbike. It debuted at the Milan Show in November 1985 and took the bike world by storm with its integrated bodywork enveloping the mechanical package.

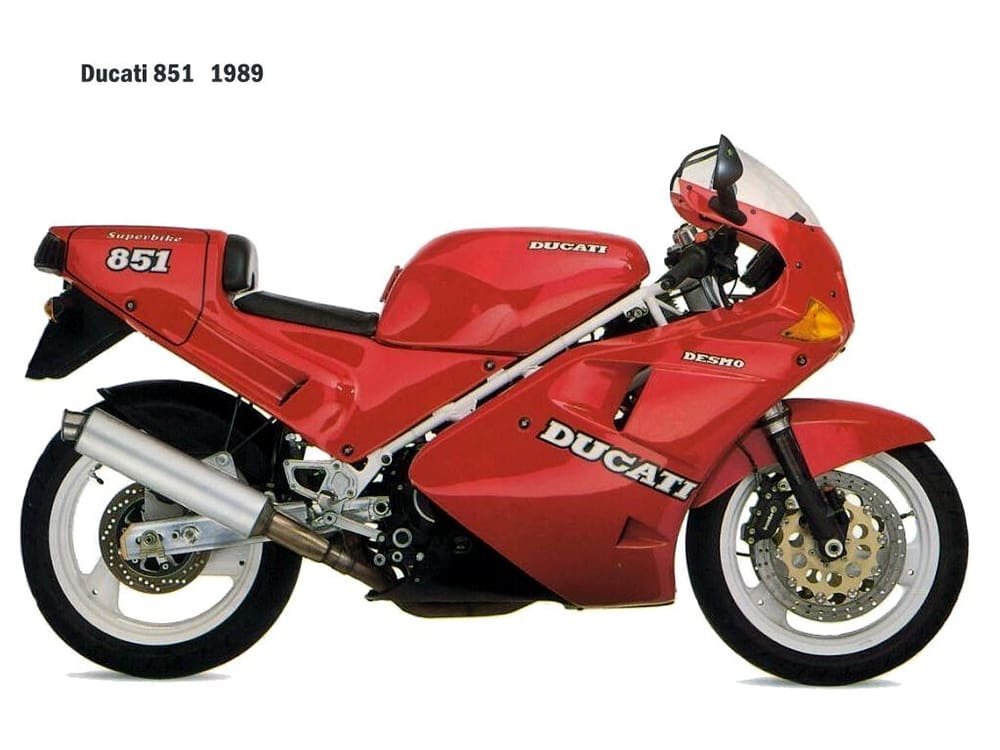

The performance limitations of the Paso’s air-cooled desmodue two-valve engine led the Castiglionis to approve Bordi’s plans to develop a modern fuel-injected, liquid-cooled multi-valve Ducati superbike engine.

The prototype desmoquattro debuted in 750cc guise in September, 1986. From here came the 851 the following year, and in due course the 888 – all designed by Tamburini, who was also responsible for the new, and far more effective, generation of Cagiva 500cc GP racers that appeared in 1989.

These included the mouth-watering carbon-framed 1990 version, and eventually the V593 that John Kocinski took to a third place in the 1994 500GP world championship.

But Massimo’s talents weren’t confined to high-performance products. He was responsible for the Mito 125, which made its debut in 1989 and was a small-scale replica of the factory Cagiva 500GP racer – which Massimo also designed. This teen idol two-stroke was every kid’s dream. Valentino Rossi won his first road race title – the 1994 Italian 125cc Sport Production crown – on a Mito and its timeless appeal kept it in production for 23 years, until emissions finally killed it off in 2012.

In 1990, Ducati achieved the Castiglionis’ aim of winning the World Superbike Championship, with French rider Raymond Roche aboard an 851 desmoquattro. It would be the first of seven world titles won by Tamburini-designed Ducatis.

But the best was yet to come from the Michelangelo of motorcycles as Massimo had by now been dubbed. In 1989 he began work on what would become the 916. It had low-set headlights, single-sided swingarm, exhausts beneath the seat and shrink-wrapped bodywork little wider than a 125 Mito. Carl Fogarty’s victory in the 1994 World Superbike series in the bike’s debut season confirmed it went as well as it looked.

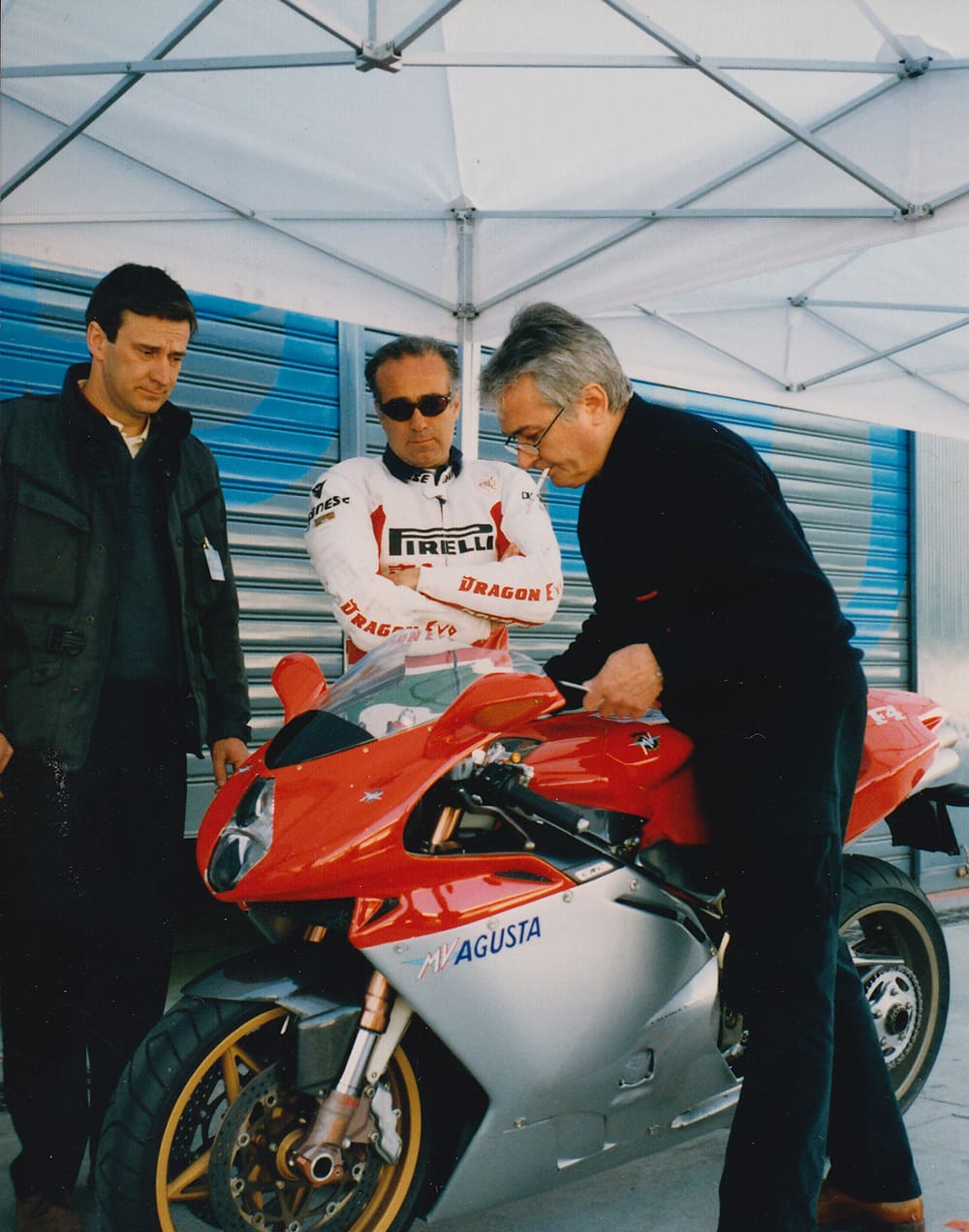

The 916 he went on to develop was a landmark motorcycle, with 72,696 sold, but that wasn’t enough to prop up the crumbling Cagiva empire and American financiers TPG purchased Ducati in 1996. Tamburini opted to stay with Cagiva and the result was the MV Agusta F4 750, unveiled to huge acclaim at the 1997 Milan Show. But deep in debt, the company was bought by Malaysian car manufacturer Proton in December 2004. A year later it sold MV Agusta to Italian finance company GEVI. As part of the restructure, Massimo was granted a two-percent shareholding in the relaunched company, so when Harley-Davidson acquired MV in August 2008 for $109 million, he was finally able to enjoy the fruits of four decades of hard work – and resume work on a project he regarded as unfinished business, the Husqvarna STR 650 CRC prototype. Launched in 2006, it was Massimo’s first attempt at an off-road machine, combining street practicality with supermoto performance. Sadly, it never reached production.

When early meetings with Harley-Davidson management revealed he’d no longer have the freedom to see a project through from initiation to production but would be expected to create prototypes and hand them over to others for final development, Massimo took voluntary retirement. He signed a no-compete clause that prevented him from designing any new bikes for three years. “But on January first, 2012, I will be back in the workshop building my next motorcycle, after three years spent refining every detail!” he promised me then.

The project was a MotoGP bike built for the EVO class, using a BMW S1000RR engine and incorporating numerous technical innovations. It never came to fruition after lung cancer claimed the life of his friend and patron Claudio Castiglioni. It was tragically coincidental that Massimo should contract the same disease. And for the same reason – he was an inveterate smoker for most of his life.

Massimo rarely appeared in public, a reluctance that brought accusations of arrogance or reclusiveness. The fact is, he was shy and entirely focused on the job in hand.

Time meant little to him. I’ve been at the CRC design studio after 10pm with a nearly full team of modellers and engineers there for whom this was clearly a regular occurrence. He was a hard taskmaster, but his passion was infectious and he led by example, though he was impatient with those who failed to live up to expectations. I never witnessed his apparently frequent phone-smashing stunts after failing to get a supplier to meet a promised delivery date or quality mark but I know CRC manager Paolo Bianchi kept a bulk supply of receivers on hand for the inevitable need to replace one.

But most of all Massimo had a depth of vision and an intense attention to detail that resulted in the most wonderful motorcycles, which remain as a memorial to the talents of the progettista par excellence. Massimo Tamburini is gone, but the bikes he built over 40 years ensure he

won’t be forgotten.

Story & photography Alan Cathcart