This was not a ‘wink-wink, nudge-nudge, say-no-more’ moment. And invariably the response would be “I’ve had her over the ton”. Though in very few instances, was this actually true.

It wasn’t until 1934 that an official Australian record was set when Bill Thompson managed a two-way average of 112.5mph (181km/h) over the flying mile in his Type 37A Bugatti, a record that held for more than 20 years. In 1938, it was established that motorcycles could be just as fast as four wheelers when Bill Barker’s 998cc J.A.P.-powered Zenith covered the flying mile at 118.42mph (190.57km/h), which was only marginally eclipsed by Peter Whitehead’s E.R.A. Grand Prix monoposto at 118.8mph (191km/h) – before high tides on Melbourne’s 90 Mile Beach halted proceedings.

By this time, Sydney motorcyclist Art Senior had established his credentials in winning a 100-mile (160km) race at Phillip Island on his OHV Ariel 500 at an average speed 7mph (11km/h) faster than Bill Thompson’s Bugatti over the same distance. And, in 1936, Senior had already covered the flying quarter mile at a faster speed than either Barker or Whitehead. Unofficially Senior was the fastest Australian on wheels when, in August 1938, he set out to better his own record. On a straight, flat stretch of concrete pavement near Liverpool, NSW, Senior set a mark of 127.65mph (205.4km/h) over the mile.

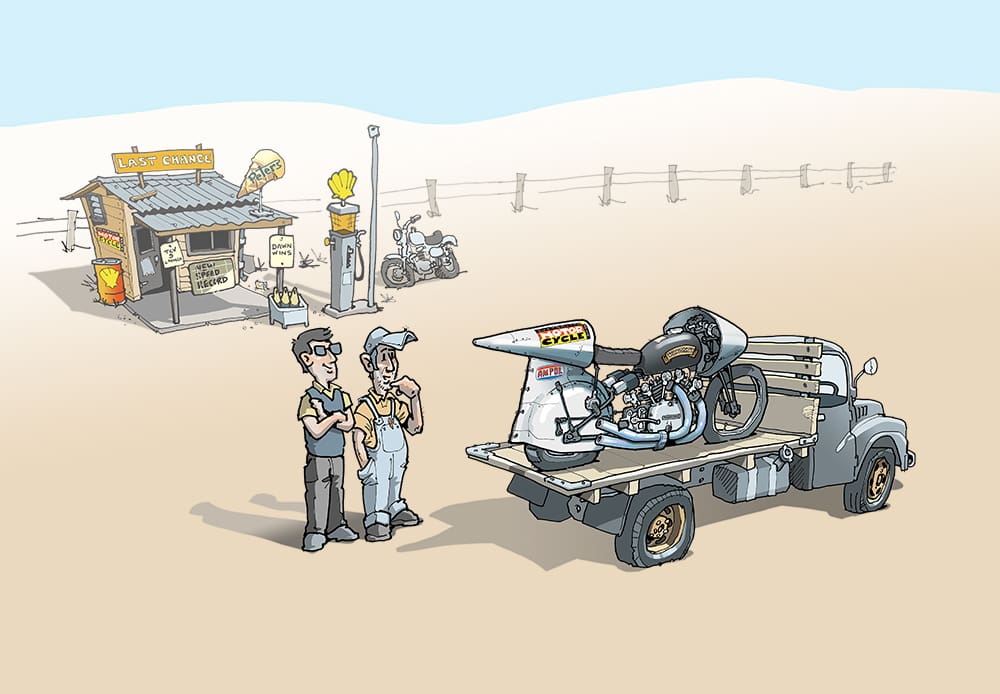

This record stood until well after World War II when Les Warton was quick to recognise the obvious attributes of the 1000cc Vincent Black Lightning; a machine built to special order as a racing and record breaking mount. In 1949 Warton took ownership of the first Black Lightning sold in Australia and in October that year, trailered the machine to a lonely stretch of the highway between Melbourne and Adelaide and established six records, both solo and sidecar, including the outright Australian Speed Record of 139.39mph (224.32km/h) over the flying mile.

Three years later, riding a Vincent Black Lightning, leading road racer Jack Ehret had easily hit a terminal velocity of 133mph (214km/h) at Castlereagh dragstrip west of Sydney, convincing Ehret that Warton’s record could be beaten. A stretch of road between Gunnedah and Tamworth was found to be suitable for the attempt but the authorities from Sydney were dead-set against the venture. Luckily the local Magistrate saw otherwise and allowed the attempt to take place in January 1953.

Despite problems with spark plugs and a dodgy gear selector, Ehret finally got the job done with a two-way average over the quarter mile of 141.509mph (227.73km/h). As far as the Auto Cycle Union and the public were concerned, this was good enough for the Australian record – if not the flying kilometre required for international recognition.

Only months later, West Australian Harry Gibson pushed the record even higher when, with advice from Phil Irving, he modified his Rapide beyond the Lightning specs. On the lonely Gingin-Muchea straight (now the Brand Highway), Harry managed to nudge the magic ‘ton and a half’ with a top speed run of 144.92mph (233.22km/h) over 400 metres (mere fractions more than a quarter mile).

Bettering 150mph (240km/h) was what Parramatta motorcycle dealer ‘Honest’ Col Crothers was focussed on when he entrusted his venerable B-series Rapide into the hands of home-grown engineering wizard Wal Hawtry. The bike was sorted but the problem was finding a venue.

After the not unexpected problems with the constabulary, the Court ruled that the Sturt Highway between Wagga Wagga and Narrandera could be closed for exactly one hour on March 28, 1954. Had the Police not raised such a brouhaha, only a few local residents may have learnt about the Australian Speed Record Attempts, but the Court Case resulted in a massive spectator turnout. Or at least as many cars, motorcycles, tractors and horses it took to clog a two-lane road through the isolated backblocks of NSW.

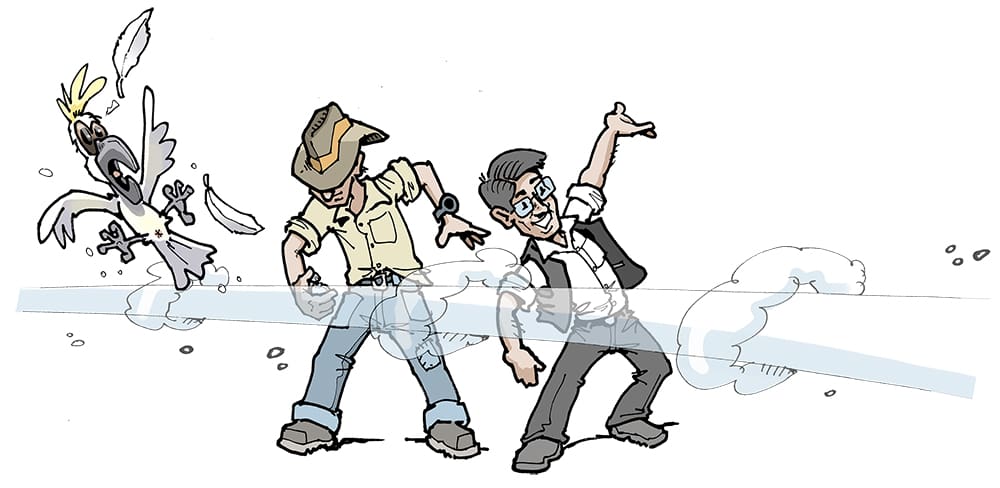

Despite the flocks of galahs that favoured the warm bitumen in the early morning sunlight, Crothers cruised through the traps at almost 150mph on his first run. That was as good as it got. The ACU’s timing equipment consisting of trip wires linked to a recorder failed completely, except when tripped by the unruly spectators.

Crothers and Hawtry remained enthusiastic and, whilst Crothers set about another legal application, Hawtry set about slipstreaming the Rapide. In an attempt to avoid the ACU’s antiquated timing system, Crothers organised an ‘Electric Eye’ timing device from J. Farren Price, Australia’s most respected timing mob at the time. Naturally the ACU stuck with manual stopwatches linked to an electronic timer (which failed repeatedly). Crother’s first run was at over 152mph (244km/h) but the timing equipment failed on the return run.

Finally, covered in feathers and birdshit, Crothers got the record he deserved. An average of 147.54mph (237.44km/h). This was more than 3mph faster than David McKay’s Aston Martin DB2/4 was able to achieve two years later. Thanks to Hawtry’s wizardry, Crother remained the fastest man in Australia. On two wheels or four.

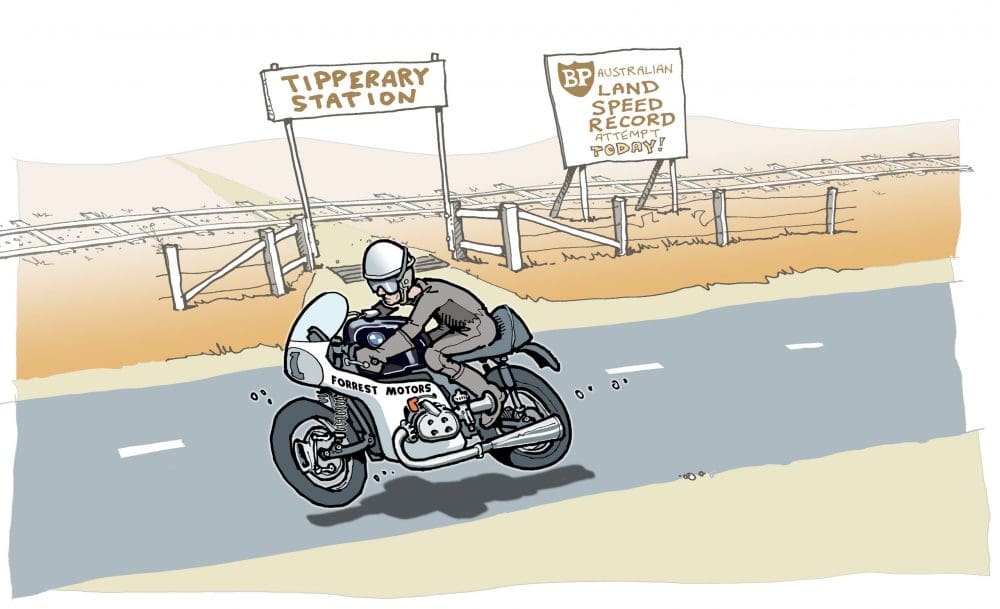

It wasn’t until early 1956 that Graham Hoinville, on behalf of British Petroleum (BP), began scouring the country for a satisfactory location to hold Australian Land Speed Record attempts. BP was willing to underwrite the exercise, however organising the venture was quite another problem. It took Hoinville over a year to eliminate all but one site; a dead-straight four-mile stretch of road beside the Coonabarabran to Baradine railway line in northwestern NSW. The road, which ran past the gates to Tipperary Station, came to be known as the Tipperary Flying Mile.

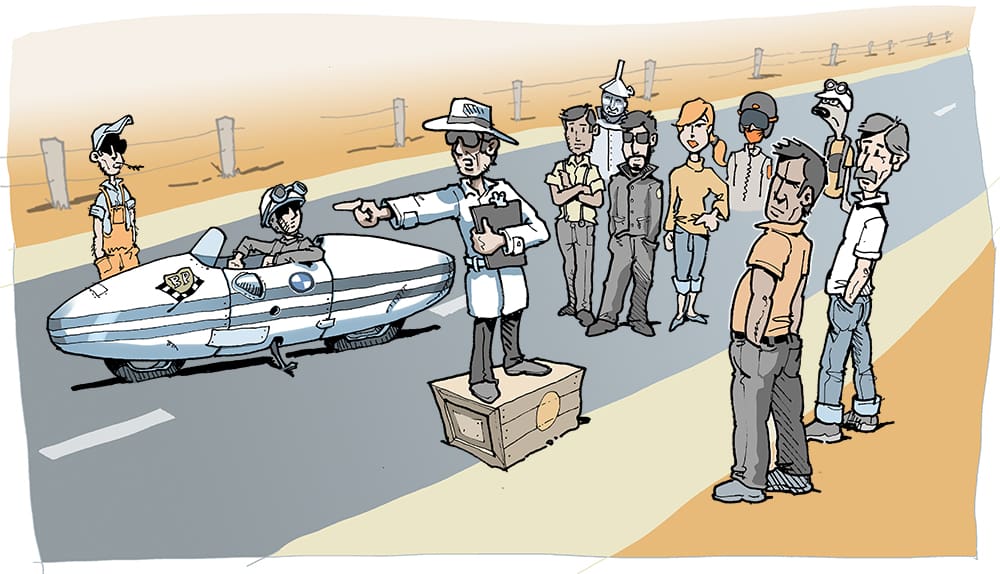

Organised by John Pryce, motor sport manager for BP, the Speed Tests were set for the last weekend in September, 1957. Unfortunately strong winds swept the district, the accompanying bushfires at one stage threatening postponement and – despite the Flying Mile appellation – in accordance with FIA rules the records were actually attempted over a flying kilometre. Although recently sealed, the road was only 18 feet wide with a distinctly high crown and narrow shoulders. Dirt tracks leading to properties joined the road at various points, and the incessant winds continually deposited loose gravel from these junctions onto the surface.

Primarily organised for automobiles, there was a last-minute decision to include motorcycles. Among those invited were Jack Forrest, with his ex-works 500cc BMW Rennsport and Trevor Pound who brought along the famous Eric Walsh 125cc BSA Bantam. Jack Ahearn had his 350 Manx Norton and a 250cc NSU Sportmax, whilst sidecars were represented by Frank Sinclair’s 1080cc Vincent and Bernie Mack’s 500 Norton.

With the Phil Irving-built 1080cc engine installed, and carrying 136 pounds (62kg) of ballast in lieu of a passenger, Frank Sinclair’s HRD outfit was first to hit the traps but the engine would not run much over 5000rpm. A pair of two inch exhaust pipes improved the revs – still 1000rpm short of potential – and the speed; giving Sinclair a new 1200cc sidecar record of 124.4mph (200.2km/h).

In an effort to raise the gearing of his BMW Rennsport, Jack Forrest and his mechanic Don Bain fitted a larger-section rear tyre. On the first practice run, the tyre grew so much due to the centrifugal force that it jammed against the swinging arm, melting the rubber, locking the rear wheel and depositing a skid mark that was still visible more than 12 months later. With no other rear tyre available, local garage owner Vane Mills vulcanised a patch on the area which had worn through to the canvas; hardly ideal for an attempt at the Australian Land Speed Record.

The bushfires continued to blaze but the wind had dropped by the time Forrest lined up for his shot at glory. With his patched-up rear tyre, Forrest blasted through the speed traps at 152mph (244km/h), but the BMW was wobbling almost uncontrollably.

Harry Hinton Senior, who was assisting Jack Ahearn, advised Forrest to hold third gear and use higher revs. On the return run, the wobble became so bad that Forrest was forced to shut the throttle completely, sailing silently over the line with a dead engine. The culprit was again the rear tyre; a huge bubble had appeared on the sidewall and it was a miracle it didn’t blow. Still, the average for the two runs, at 149.068mph (239.901km/h), was a new outright Australian Motorcycle record which was to stand for over 15 years.

For a few hours Jack Forrest also held the title as the fastest man in Australia. Then Ted Gray pushed his 283 cubic-inch V8 Corvette-powered ‘Tornado’ to an Australian Land Speed record of 157.7mph (253.7km/h).

Never again would motorcycles be able to match the outright speed of their four-wheeled brethren on Australian soil.