The middleweight soft-roader category of two- and three-cylinder-powered sporty roadbikes having some unsealed-road ability has become quite crowded. Established contenders from BMW, Suzuki, Triumph and Ducati had had to make room for the Kawasaki Versys 650, the BMW F 700 GS and Triumph’s junior dual-sports Tigers.

Yamaha’s unsung hero, the TDM900, had been plugging away manfully as a competent soft-roader since 2002, largely unnoticed by Australian buyers while performing strongly in overseas markets.

I put its lack of sales success here down to its looks. Australian buyers seem to expect bikes that can handle a bit of dirt and gravel to look a bit tough with it. While the TDM has the chassis and the underpinnings to do the hard yards – things like a torquey but predictable engine; robust suspension with extra travel; decent ground clearance – its slick styling, aimed at a European audience, seems to have been judged a bit too city-sleek for rugged-road touring in

our sunburnt country.

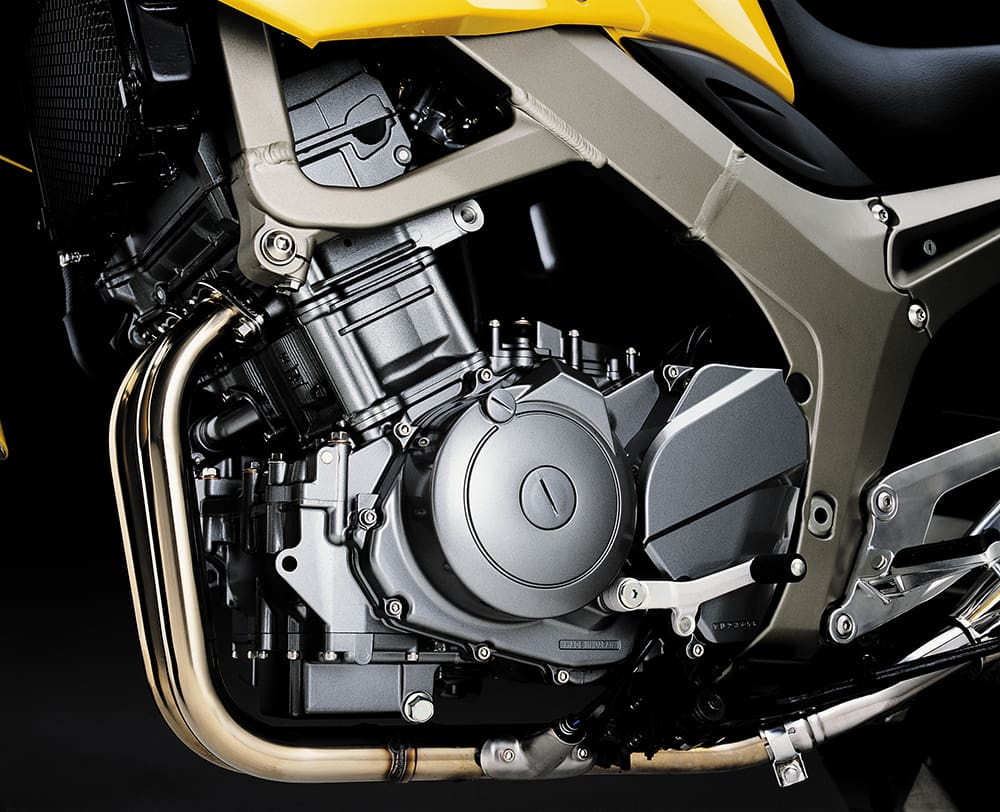

Its arrival in 2002 revealed a much revised and improved bike compared with its TDM850 predecessor. The 900’s new aluminium frame is much lighter and much stiffer. Its liquid-cooled parallel-twin engine, which incidentally is descended from the Paris-Dakar-winning XTZ750 engine, was heavily revised internally as well as copping a bigger bore. While its peak power of 63.4kW (86hp) at 7500rpm represented only a five-percent improvement over the 850, its max torque of 89.2Nm at 6000rpm represented an 11-percent gain. Perhaps more important for its intended duties was a significant lift in torque throughout the low to midrange area. Other changes included moving from a five-speed gearbox to a six-speeder and electronic fuel injection replacing carbs. The engine retained its quirky 270° crank for that loping V-twin flavour.

The TDM is a very comfortable bike that is very easy to ride. The ergonomics work well for a range of rider sizes with the upright riding position being ideal for commuting, while giving the rider great authority over the bike in fast winding-road work. There’s actually a bit of a supermoto feel to a TDM.

The clutch has a very light action and the gear selection is easy and accurate. The engine’s response to throttle inputs masks its generous torque by being linear and predictable, just right for wet conditions and unsealed roads. They can be a bit harsh on and off the throttle in low-speed log-jam traffic conditions, otherwise engine fuelling is spot-on. The engine is remarkably vibration free from idle until well past the midrange and is very quiet mechanically.

The R1-derived brakes offer a great combination of power and feel.

The wheelbase, steering geometry, and perhaps the 18-inch front wheel (the rear is 17-inch) contribute to the bike’s stability in fast bitumen sweepers as well as on the dirt. The downside is a slightly vague feel to the front end as you fling it into tight stuff – the long-travel suspension no doubt contributes as well. It’s a characteristic it shares with some other dual-sports bikes, and it’s a thing you soon get used to. TDMs used regularly on rough roads will benefit from aftermarket spring and valving work to reduce suspension harshness and bottoming in those conditions.

The TDM is very easy on fuel unless you’re flogging it. The 20-litre fuel tank is good for a safe highway-touring range of 380km or better.

If someone tells you TDM means tedium they either haven’t ridden one or if they did, they didn’t get stuck into it enough to reveal its charms. I’ve seen a TDM more than holding its own in the mountains in close combat with a 955 Triumph Tiger and a TL1000-powered Cagiva Navigator, all at full noise.

For me, the bike’s combination of versatility, rider-friendliness and fun-factor means that a TDM is a very fine UJM – a true Universal Japanese Motorcycle.