Sixty-three years ago, Keith Campbell won the 350 Dutch TT at Assen and the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps, iconic circuits that required riding precision. He became the first Australian to claim two world championship GPs in a calendar year, and captured the lead in a title race he would eventually win.

The Assen victory on 29 June 1957 was special on several counts for the then 25-year-old from the Melbourne suburb of Prahran. Two years earlier he had been part of a riders’ strike at the circuit over poor starting money and was suspended from GP racing for six months. This time the Netherlands would be remembered more happily.

It was also special because this was Campbell’s first world championship victory, head-to-head on a single-cylinder Moto Guzzi against dual Isle of Man TT winner Bob McIntyre on a four-cylinder Gilera.

On top of the 350cc wins, Campbell impressed in the Assen and Spa 500 races on the famed Guzzi V8 before mechanical trouble intervened.

The backstory to Guzzi’s newest works rider becoming its chief 1957 title hope begins in July 1956, when two standout rides on private Nortons in the non-championship Swedish GP at Hedemora earned Campbell a works trial. He signed with Guzzi.

Even before the championship had started, two major contenders were sidelined by crashes at the Imola Gold Cup meeting – defending 350 champion Bill Lomas (broken collarbone) and Gilera’s multiple 500 champion Geoff Duke (dislocated shoulder). Dickie Dale scored the Guzzi V8’s first major victory in the 500 race, with Campbell third on a 500 single.

The virtual speed bowl that was Hockenheim hosted the opening title round. Gilera’s home-grown star Libero Liberati claimed the 350 and 500 GPs, the latter at an average of some 200km/h. Campbell retired his 350 with gear-selection problems.

Round 2 was the IoM TT. Duke was not available and Liberati had not ridden at the Island, so McIntyre led the Gilera assault. On Duke’s recommendation he was backed by Australian Bob Brown – quite an endorsement given it was only Brown’s second TT and his first ride on four-cylinder racers. They were challenging machines to ride on bumpy circuits because the engine’s revs would skyrocket when the rear tyre left the ground.

It was McIntyre’s first chance to ride factory Italian machines in his favourite event and the Scot wasn’t about to waste it. There were no seedings for the faster riders; he rode with starting number 79 in the 350 and 78 in the 500 TT.

Guzzi’s 1955 350 winner Lomas was a non-starter. Collarbones were not plated in the 1950s, so Campbell, Dale and John Clark represented Guzzi.

Campbell had not raced at the Island since the 1952 Manx GP, the races for amateurs. He’d competed elsewhere in 1953 and 1955, missed 1954 after sustaining an injury during practice and been suspended in 1956. Nonetheless, Duke, in his 350 TT preview for Motor Cycling, said Campbell surprised him in Monday morning practice “considering his comparative lack of knowledge of the circuit. He seems quite sure of himself, being both fast and

safe, and he looks like going much better than I originally thought.”

Bob Mac was the undisputed star of the ’57 TT. He lapped at 97mph from a standing start and led the seven-lap 350 race throughout, winning by three and a half minutes from Campbell, with Brown third, then reigning 500 champion John Surtees (MV) and Australian private entrant Eric Hinton (Norton). There were five Australasian riders in the top 10.

Dale was the bad-luck story of the race, suffering a broken windscreen when he struck a bird and then crashing on spilt oil.

Campbell’s post-race comments were extensive for the reporting style of the day, saying he had several anxious moments. The first occurred when he passed a slower rider with only an inch to spare, due to the latter drifting out on a bend. He later encountered wet tar at the Mountain Box and had a slide in the closing stages of the race. Campbell said he missed a gear change by the grandstand at the end of the first lap and touched a valve (which usually meant race over on a Norton), losing 200rpm, which he mainly noticed on the Mountain climb. He missed another change on the fourth lap without serious consequence. He didn’t realise he was in the hunt for the podium until the third lap, but did not let the news excite him.

McIntyre wrapped up the week by beating the magic 100mph barrier four times in the eight-lap 500 TT, the longest world GP championship race ever. Surtees and Brown completed the podium, ahead of Dale on the Guzzi V8 (albeit running on seven cylinders) and Campbell on a Guzzi single after a minor fall on the last lap.

Three weeks later came Assen, a meeting that changed the course of two championships.

Lomas’s comeback was ruined when he fell during practice, sustaining head injuries and a fractured arm. By the time he’d recovered, Guzzi had withdrawn from racing and, unable to secure another factory ride, the Englishman retired.

Guzzi then lost another rider when Dale crashed out of the Assen 350 race, breaking his ankle.

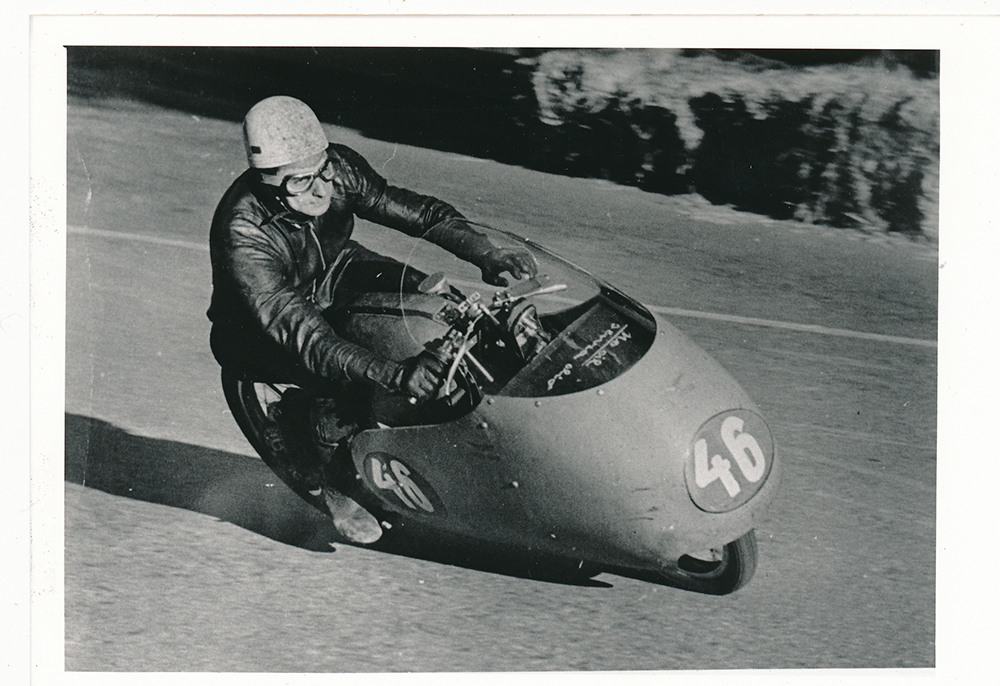

However, the real race action for the crowd of 100,000 was McIntyre versus Campbell, the Australian using the Guzzi single’s advantages of lighter weight and a lower centre of gravity to beat the more powerful Gilera four.

Vic Willoughby, technical writer for The Motor Cycle, was a great fan of McIntyre. But 30 years later he still tipped his hat to Campbell for this aggressive but thoughtful display, using his machine’s advantage to the full.

“Bob would gobble up Keith on the straights and clap on the anchors. Keith would brake 50 yards later, dive under his handlebar and just fling it into the corner,” Willoughby said.

Campbell won, easily bettering Lomas’s race record, with Liberati third and Australian private entrant Keith Bryen fifth on his Norton.

Guzzi designer Giulio Carcano gave Campbell the best V8 for the Dutch 500 TT. He had trouble starting, but was soon chasing Surtees’ leading MV and had closed to within 15 seconds when the clutch failed.

McIntyre meantime made a pit stop to check his suspension and then tore after Surtees, breaking the lap record before crashing out of second place. He was seemingly uninjured, but then suffered severe recurring headaches and missed the next GP in Belgium. Surtees recorded his only classic victory of the season.

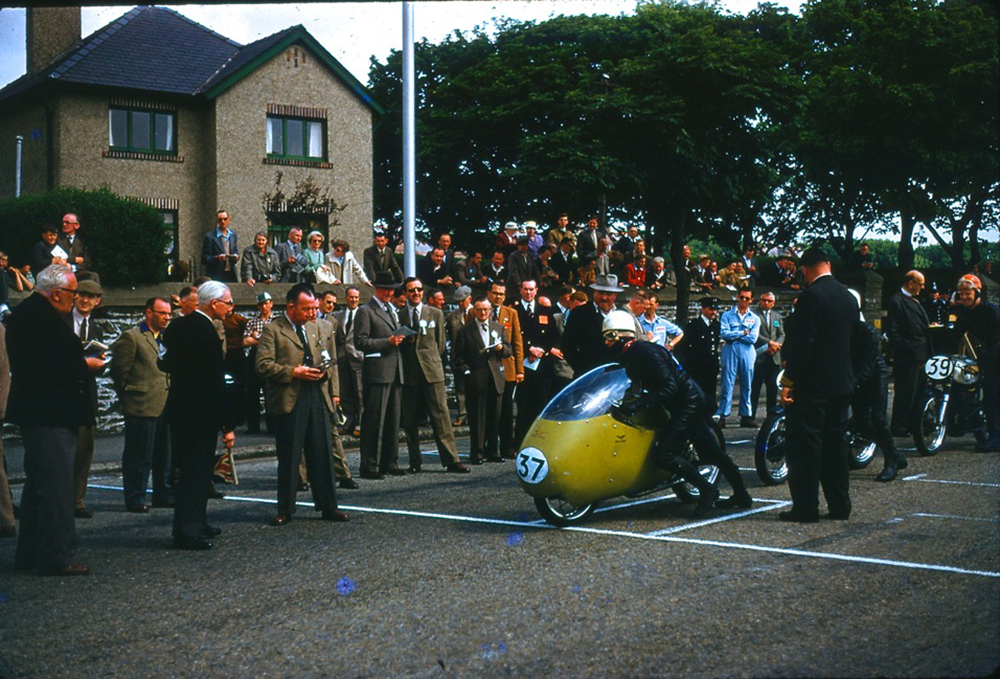

Campbell’s race average speed in the 350 event was quicker than Liberati’s ride to second place in the 500. Bryen had another impressive ride to sixth place and Guzzi management immediately recruited him to support Campbell at Spa-Francorchamps. Gilera also called in Brown for the 350 and 500 races on 7 July, so the Belgian 350 GP grid had three Australians on works Italian machines.

Two years earlier, Campbell had recorded his first GP podium at Spa. Riding a self-tuned Norton he finished behind works riders Lomas (Guzzi) and August Hobl (DKW) and beat three more works bikes. Factory managers of the day took notice of results on the Ardennes.

The late Bob Edmonds, Campbell’s helper in 1955, remembered something else – that fellow privateers thought Campbell had factory parts in his bikes. But Edmonds said the secret was something Campbell learned at the Velocette race shop on his first trip to Britain in 1951 – pay meticulous attention to setting the valve and ignition timing.

Campbell bolted from the green light in the 350 race (yes, a starting light is mentioned in reports).

New records were in the offing due to significant circuit upgrades, with the tarmac resurfaced and widened by a metre, La Source hairpin widened (reducing the circuit length by 20 metres to 14.1km) and trees around the daunting circuit cut back by three metres.

Campbell was four seconds ahead by the time he reached the famed bends at Burneville on the second lap, which was only 16km into the 155km race. He won the race by 12.3 seconds from Liberati, having averaged 183.9km/h, with Bryen third, Guzzi’s veteran tester Alano Montanari fourth and Brown fifth.

Bryen recalled being amazed by the sophistication of the Moto Guzzi 350 single and the team’s operation, saying he had to remind himself he was on a single: “Then I found a problem. The bike handled beautifully in one session, but in the other sessions it weaved on the straights. Keith Campbell said it was the streamlining; he just gritted his teeth and carried on. We tried different settings, but I put it down to the tyres, which they changed after the first practice session. Carcano told me on the Saturday night that the old tyres were in the rubbish bin behind the team hotel in Stavelot, so we took a chance and put those tyres back on.

“In the race, the bike handled like it was on rails. Keith Campbell won and I had a battle with Liberati for second, eventually deciding third place was better than taking a tumble in my first Guzzi ride.”

Campbell lined up on the Guzzi V8 for the 500 race at Spa, with Brown on a Gilera and Bryen on his private Norton, but inspired after his podium finish in the 350 GP.

What happened next was extraordinary.

There were troubles with Liberati’s engine while it was being warmed up, so the team manager commandeered Brown’s bike. This was in contravention of FIM rules and deeply upset Duke’s sense of fair play. Nevertheless, Liberati was allowed to continue in the race and won, ahead of Jack Brett (factory-assisted Norton) and Bryen.

Liberati was stripped of the victory, but months later was reinstated on appeal and is still in the record books as having won the race.

The controversy deflected attention away from Campbell, who had a brilliant ride while the Guzzi V8 lasted. He posted the fastest lap at 190.8km/h. And his 350 race average would have been good enough to finish second ahead of Brett.

Sadly, Australian private entrant Roger Barker, a double top-eight finisher at Assen, died at Schleiz in East Germany the same day. That was reported on radio and in print in Melbourne, but Campbell’s second GP victory was not.

Fresh from their Spa successes, Campbell and Bryen loaded two Guzzi singles into Bryen’s truck and headed north to Hedemora, where Campbell won the non-championship 350 and 500 GPs, the first in bucketing rain on the Saturday and the 500 in bright sunshine.

The Ulster GP was the next championship round. The 350 race started on a damp track and ended with a Campbell-Bryen one-two for Guzzi. Title secured. Liberati was an unhappy third, as clearly shown in the presentation photographs. Bryen used the word ungracious. He did, however, lead Duke and McIntyre to a Gilera trifecta in the 500 race.

Campbell missed the final GP of the season at Monza on 1 September, having crashed and broken his shoulder during testing. Handling problems with the V8 saw it withdrawn from the meeting.

McIntyre won the 350 race, but another severe headache ruled him out of the premier class, which Liberati won from Duke to claim the championship. In what proved the last hoorah for Italy’s golden era, four-cylinder Gileras and MVs took the first seven places for the home team.

In late September the sky fell in on the works careers of Campbell and Bryen when Moto Guzzi, along with Gilera and Mondial, withdrew from GP racing, officially citing falling bike sales in Italy. The Golden Era was over, with the press dubbing the next era from 1958 until the Japanese factories came to GP racing the Dark Ages.

Full fairings were banned in 1958 and racing in the top two classes was dominated by MV’s John Surtees, usually with a back-up rider and then a flock of private entrants on British singles.

Campbell, who had been a successful private entrant from 1953 to ’56, reverted to Nortons and also raced a Maserati 250F GP car. At Spa on 6 July he split the MV team of Surtees and John Hartle to finish second in the 1958 Belgian 500 GP.

A week later Campbell won an international 350 race at Cadours, near Toulouse in France. But leading the 500 race he hit an oil spill and went off the circuit. He was killed instantly. He was 26.

Words Don Cox Photography Gwen Bryen, EMAP, DRents Archive, Bob Edmonds, Per Hedstrom