It was the mid-1980s and things were looking up for Harley-Davidson. It was finally relieved from the grip of AMF ownership and enjoying huge success with its new range of Evolution engined motorcycles. Harleys were more reliable than ever before, thanks to Porsche’s input in the design and development of the Evo engine.

Hugely active in flat track racing, Harley had learned that participation and success in motorsports pays off handsomely when it comes to goodwill and good PR. Fans rode their Harleys to races, cheered for their idols and felt good about themselves when they won, which they did a lot.

About the same time Superbike racing became extremely popular, especially in the States, where the racing class had emerged and flourished a decade earlier. Twins were allowed a 33 percent higher engine capacity than the four-cylinder superbikes, which were limited to 750cc. Ducati especially benefited from this, finding the perfect arena to use its new 851 prototype desmoquattro racers and had no issues signing up former Grand Prix riders to race them.

Ducati’s 851 made its racing debut at Daytona in March 1987, before the production version was unveiled to an adoring public a few months later, which created an immediate stir. Harley watched on and, combined with the rapidly rising popularity of the Superbikes, made a decision to begin development on an all-new, American-made superbike contender.

It was 1987 and, remarkably, it was the first time in H-D’s long and storied history that it had developed a racer from scratch. Up until then, all H-D factory racers were based on existing production models that were heavily adapted for the circuit. But there was another reason why this decision stands out. Harley needed to build 50 homologation copies.

Just like today, there was a clause in American Superbike regulations that prescribed that Superbike racers had to be based on production machines, so Harley not only had to build one Superbike, it needed 50 homologation models, too.

Harley’s vice president of development Mark Tuttle was put in charge of the project. He received support from known H-D tuner Jerry Branch and Dick O’Brien, the former head of Harley’s race department. The firm’s development engineer Mark Miller received the task to establish the engine concept and make the first design drawings. In order to concentrate as much mass as possible in the engine and gearbox, the decision was made to develop a 60-degree V-twin. This also gave more options for its frame design and geometry, thus creating better handling possibilities.

Harley chose fuel injection as a starting point. Since it was a completely new technology for the American brand at the time, it decided to team up with Roush Racing. Harley simply did not have enough in-house knowledge on how to unleash serious engine power from cylinder head design with their complicated thermodynamics, flow, inlet and exhaust design, and making this all work with fuel injection technology and engine management systems.

But thanks to its work in NASCAR, Trans-Am and Drag racing tuning, Roush Racing had the experience H-D needed. Steve Scheibe, a young engineer at Roush and in his free time an amateur road racer, was assigned to the Harley project. This led to Scheibe’s appointment to Harley-Davidson in 1991, where he’d lead the five-headed team that would develop Milwaukee’s Superbike even further. As well as the superbike, or indeed because of it, Scheibe was also tasked with developing more modern engine techniques for future road-going models. This eventually came to light in 2001, 10 years after Scheibe joined Harley.

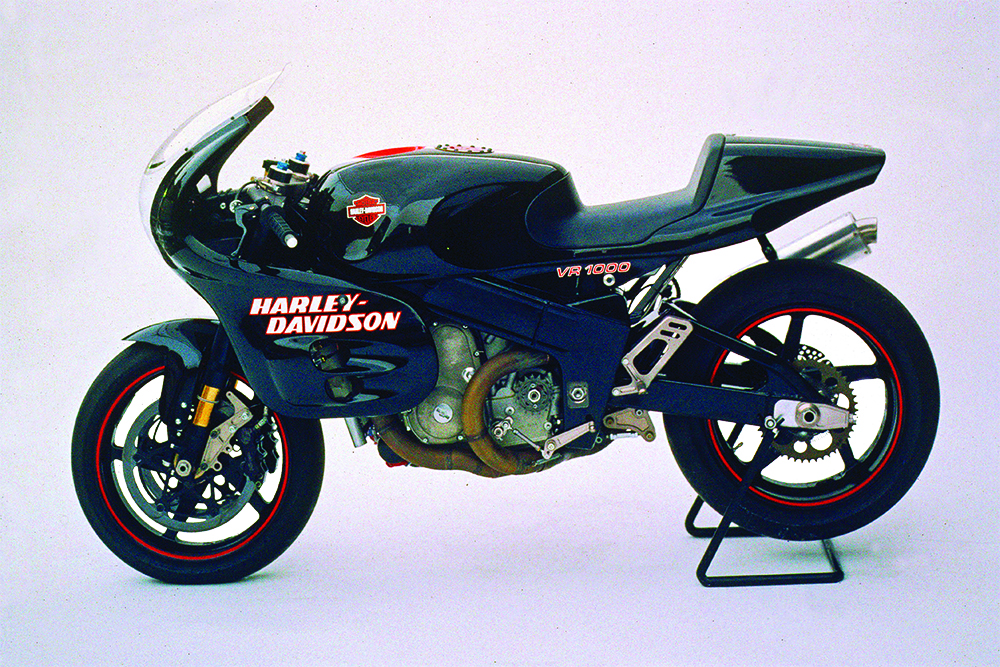

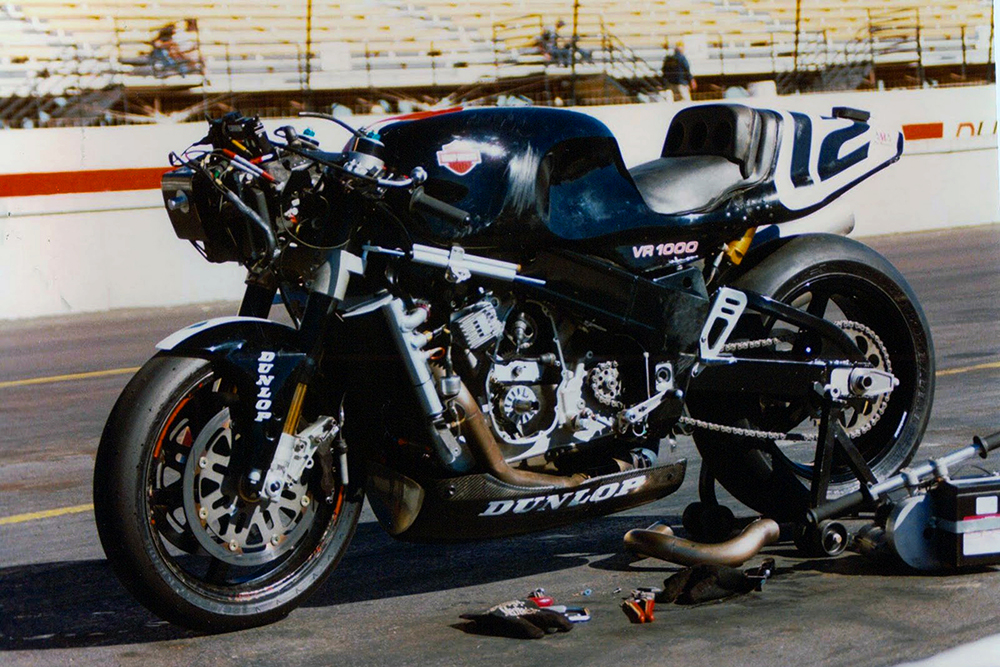

Tuttle and Scheibe started their assignment in 1987 and developed an advanced eight-valve DOHC liquid-cooled V-twin engine. It was the first Harley-Davidson engine that featured double-overhead camshafts. A bore and stroke of 98 x 66mm gave a capacity of 996cc. Sound familiar? Indeed, the same figures as the Ducati 996 factory Superbike with which Aussie Troy Corser won the 1996 World Superbike Championship! The crankshaft ran on plain bearings to reduce friction and titanium Carillo conrods connected the large-diameter crankpin with the forged Wiseco three-ring slipper pistons. The aluminium cylinders were chrome plated, the compression ratio was 12:1, and the rev limit was initially set at 10,800rpm – quite a bit lower than Corser’s desmodromic Ducati!

The design team also employed a counterbalancer which weighed 800 grams and was directly driven by the crankshaft. The goal was to minimise vibrations, as vibrations cost power and can cause reliability issues through not only damage to the engine, but also the bike’s other parts. The camshafts were driven by chains.

Each cylinder had four valves, the titanium inlet valves had a diameter of 39mm, the exhaust valves measured 33mm and the included angle was set at 32°. Each combustion chamber was fed by a single Weber-Marelli injector which was mounted in a 54mm diameter throttle body. The Magneti-Marelli ECU used at the time was capable of firing only one injector at a time and was the same unit used in some Fiat cars.

Rather special was the fact that both cylinders did not receive the same mapping. This was done to enhance midrange (4000-7000rpm) performance without sacrificing top-end power. In fact, Ducati would introduce this technology on its 1993 World Superbike contender.

A primary chain ran the dry, multi-plate (nine metal and eight fibre plates) slipper clutch and five-speed gearbox. The big-bore exhaust system was tapered and halfway along the collector pipe a SuperTrapp silencer was mounted. The passing of noise tests could be fine-tuned by adding more baffle plates in the system.

Eventually a rolling chassis was designed by Mike Eatough, after Erik Buell designed a series of prototype frames, some of them doubling as fuel tanks. Eatough joined Harley-Davidson after the Motor Company took over British motorcycle manufacturer Armstrong. He also had developed a number of road-race frames for Armstrong, including the very first GP racer with a full carbon fibre frame, the Armstrong CF250.

Eatough developed an aluminium twin-spar frame – with a steering-head angle of 67º and with 96.5mm of trail – with an adjustable pivot for the aluminium swingarm. He then gave both Erik Buell and Harris Performance from England the assignment to build it. Eventually he chose Harris to fabricate the last of the prototype frames, before American firm Alcoa took over frame building – Harley wanted the new bike to be as American as possible.

Scheibe asked Alcoa to fabricate two types of frames; the geometry was identical, the racer’s however had the two frame halves bolted together, the later production bike frame had the sections welded together. A fully adjustable Penske monoshock with 135mm travel looked after rear suspension duties, while a fully adjustable 46mm Öhlins fork with 119mm of travel looked after the front.

By May 1993 a prototype was taken to Michigan’s Grattan Raceway for secret tests. It delivered a power output of 147hp at 10,800rpm at the crankshaft – crucially 5hp more than the 926cc Ducati 888 that was raced in the American AMA championship the same year. It was heavy though, the VR1000 weighed in at 172kg race ready – substantially more than the 162kg Superbike weight limit at the time.

The development of the VR1000 had taken seven years, which was way too long. Financially, Harley was doing very well but not particularly eager to spend too much on the Superbike projects. In the years that followed this situation did not change, which delayed its development.

Harley was still required to build a homologation series of 50 machines and get them approved. In the USA, homologating a roadbike isn’t easy, especially when it comes to environmental emissions and sound. Harley had decided to develop a pure racer, not a streetbike that took the road-legal requirements into consideration.

However, the rules did not specify where homologation had to take place. Harley made an analysis of homologation rules in other Western countries and discovered that Poland – not yet a part of the EU – had an extremely liberal vehicle law. Not many changes were needed to convert the circuit VR1000 into a street legal machine.

The required changes led to a lower output of 125hp at 10,000rpm which, at the time, was a beastly high amount of power for a twin-cylinder roadbike. It made the VR1000 by far the most powerful, street legal twin available to the general public. It also was the first production motorcycle that was factory equipped with a slipper clutch.

But what made the VR1000 really special was the fact that it was a pure Superbike racer licensed for the road. It was specifically designed as a racer and on top of that, one that could be easily developed and tuned further.

The Harley design guru, Willie. G Davidson, designed the carbon-fibre bodywork and painted it in the firm’s traditional black-and-orange racing colours, but in an unconventional application; one side of the VR was black, the other side orange. Maybe that justified its steep selling price of US$49,950, which was roughly twice as much as the most exclusive sports models from Italy and Japan at the time. A total of 50 VR1000s were built; eight were reserved for H-D’s works racing team and the rest were sold.

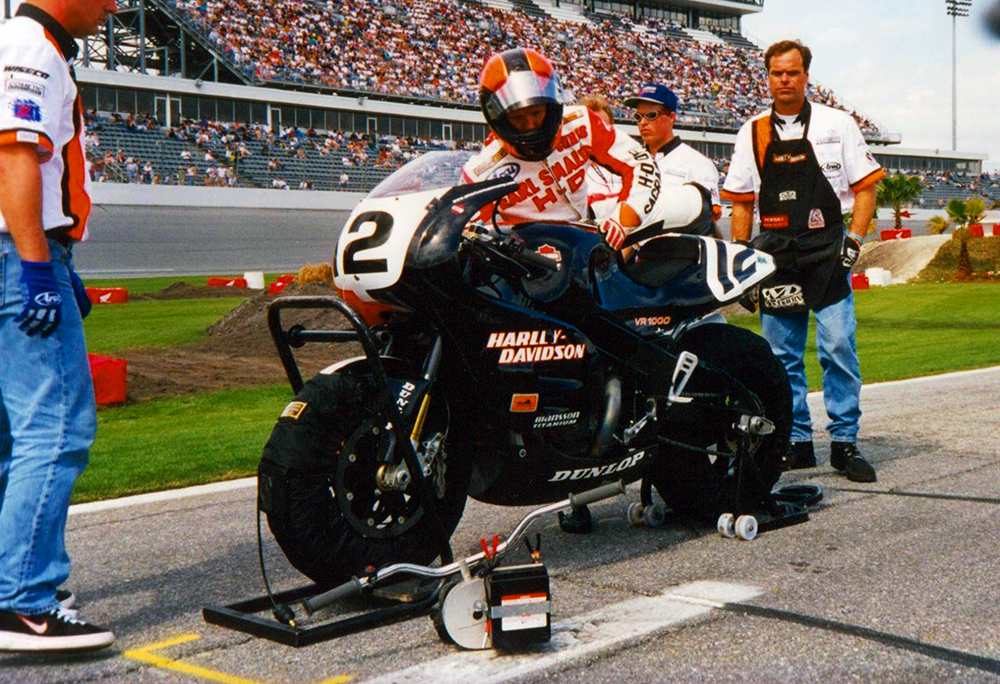

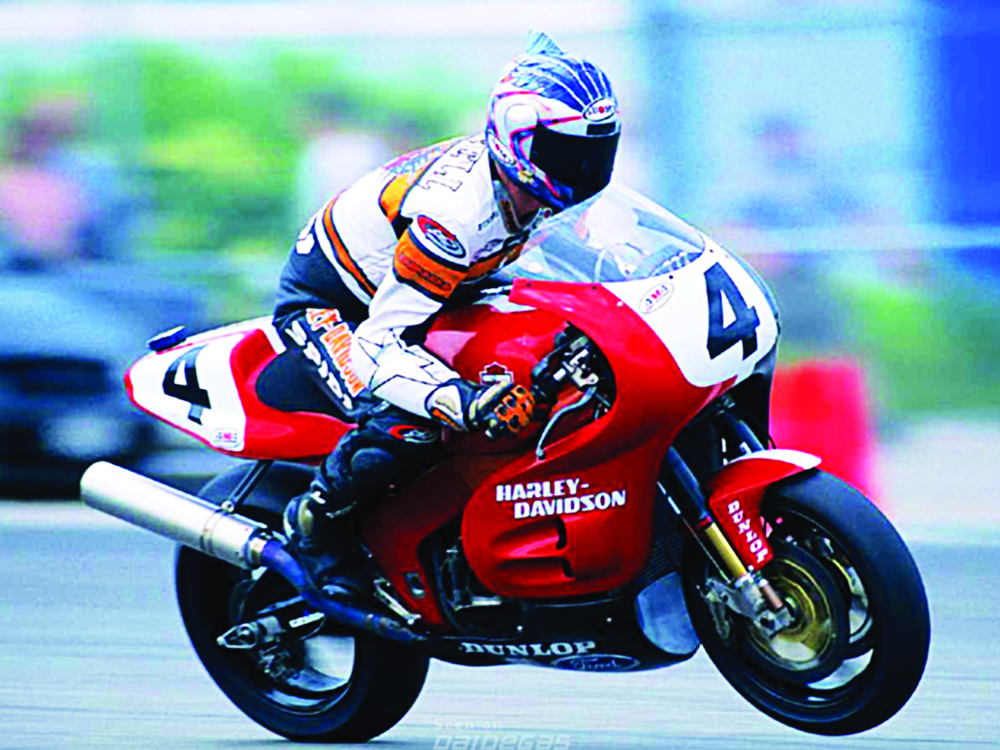

Canadian Miguel DuHamel gave the VR1000 its racing debut at the famous Daytona 200 race of 1994. It wasn’t successful. The VR got swamped at the start and eventually retired due to mechanical problems. The rest of the season was marred by mechanical DNFs, even though DuHamel led the field on several occasions.

In 1995 Chris Carr captured pole position during the American Superbike race at the circuit of Ponoma. In the years that followed the VR1000 captured several second and third places in some major races and came at times close to a win. But its engine power rose too slowly to keep up with its competitors and reliability and handling also kept being an issue.

Harley’s competitors invested vast sums year after year developing their Superbike racers and raking in world titles. Harley wasn’t motivated to do the same and, as time went on, the negative effects of this strategy became more and more a disadvantage, and the VR1000 was steadily outpaced by its competitors.

Harley, however, did give the VR a major development injection in 1999 when former World Superbike champion Scott Russell was signed to race the VR1000. It received a second injector for each cylinder and a new engine management system. The hard work on the engine paid off; power rose to 170hp at 11,300rpm, which was the same power output Ducati claimed for its 996 World Superbike racer with which Carl Fogarty won the 1999 WorldSBK Championship.

But once again, the effort wasn’t rewarded by success. It was an era when the rate of development was exponential and Harley’s competitors were not only better at it, but more motivated by world-title silverware. In 2000 the VR1000 struggled to finish in the top 10, and at the end of the season Scheibe and Russell left the Harley-Davidson works racing team. The VR’s time on the circuits was quickly running out.

Just before the end of the 2001 season Harley decided to kill the VR1000 Superbike project. To continue did not make sense to them anymore, the goodwill and good PR no longer justified the cost. The novelty had worn off and for every small step Harley made with the VR, the Italians and Japanese factories took a leap. The VR1000’s racing days were over.

Words Ivar de Gier

Photography Archives A. Herl & Steve Scheibe