We’ve already scooped the general design of the new bike, which adopts the engine from the hyper-expensive RC213V-S and slings it into an all-new cast aluminium chassis. It’s a move that’s intended to massively reduce production costs, bringing the bike below the €40,000 (AUD$62,000) price cap imposed on machines intended to be the basis of World Superbike racers. Allied to new rules that reduce the minimum production of entrants to 500, the result is a return to the now coveted HRC-made bikes that last brought Honda WSBK success – the RC30, RC45 and RC51.

And holding it back until the 2018 model year makes sense. At the end of this year Honda is expected to reveal its new inline four-cylinder Fireblade and it won’t want to draw the limelight away from that model during its introductory year. However, the 2017 Blade is believed to be developed with road use rather than racing in mind, avoiding some of the pitfalls of designing production bikes as track machines first, road models second.

According to our insiders, ideas for the bike that eventually became the RC213V-S roadbike veered in two directions within Honda’s R&D department. One camp was intent on creating the rawest machine possible – literally an RC213V MotoGP bike with the minimum of changes to make it road legal. And this group of engineers won the day. The rival idea was to create a bike that was based on the RC213V engine and technology but that would be a far more polished, stand-alone product featuring new technology above and beyond what’s already featured on the GP bike and offering a much more civilised riding experience.

While that second group of engineers lost out in the short term, it seems that in the longer run their concept is what’s being developed into the new RVF1000.

The coming of Honda’s 70th anniversary provides a useful hook for the launch of the new model, which will be a range topper but not so out of reach as the RC213V-S.

By Ben Purvis

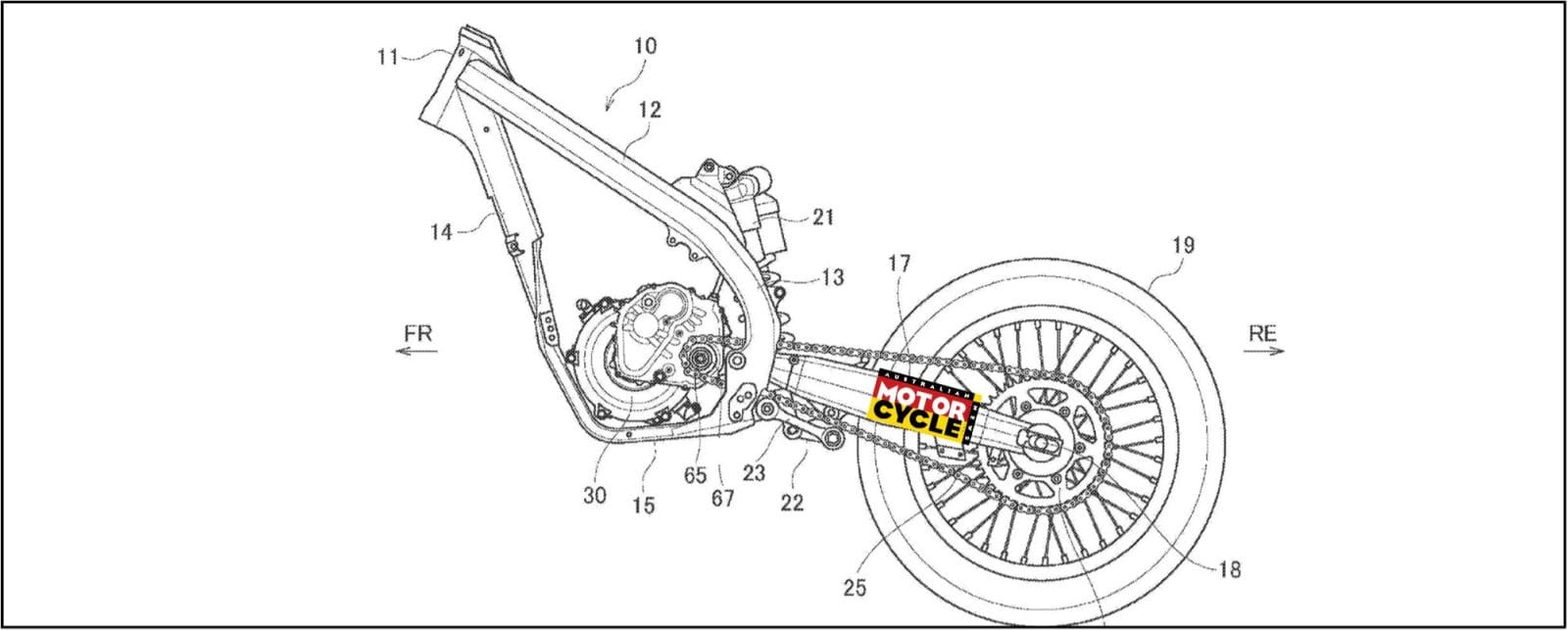

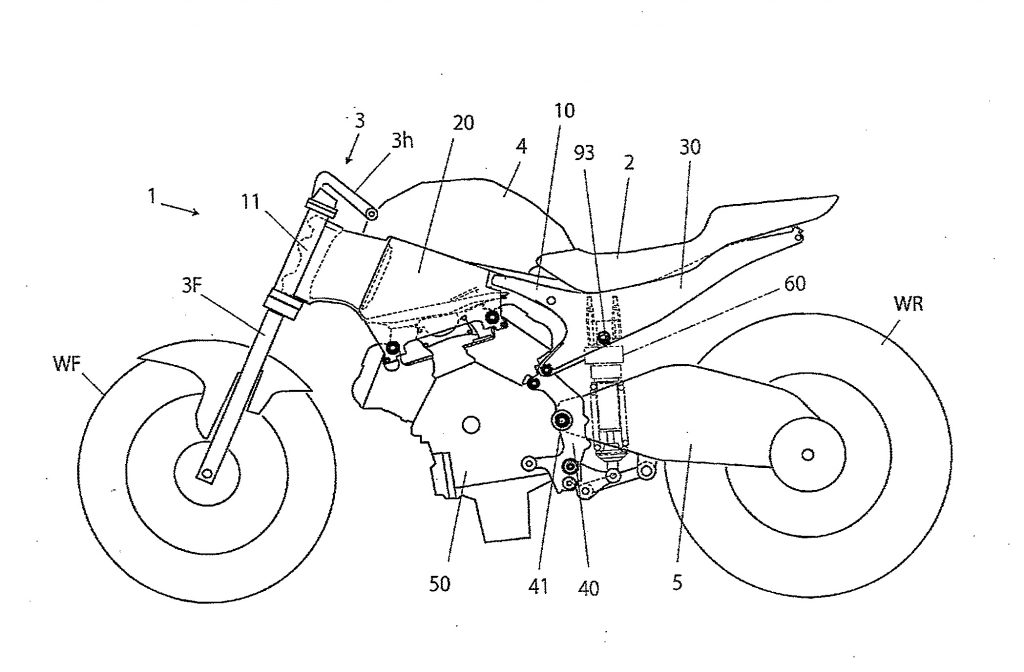

1. CHASSIS

The frame is a cast aluminium design made in three sections. Using cast aluminium means that it can be factory-made in relatively large numbers at fairly low cost

2. MONOCOQUE

Panigale-style front links the headstock to a monocoque that sits above the V of the engine and doubles as the airbox

3. SUBFRAME

Subframe mounts to the rear cylinder bank and the back of the monocoque section. It also incorporates the rear shock mount

4. PIVOT POINT

U-shaped casting braces the swingarm pivot area of the transmission

5. SWINGARM

The single-sided swingarm pays homage to the RC30 and RC45

Big RC shoes to fill

While Honda’s 2018 V4 is certain to carry the ‘RVF’ badge – the firm’s recent renewal of its trademark rights assure that – its illustrious predecessors were better known by their internal RC designations.

The RC letters were made famous by the VFR750R, launched in 1987. Of course, we all prefer to call it the RC30, since the internal code gives an appropriate distance from the run-of-the-mill VFR750F that was sold alongside it. And it really was different.

The RC30 was perhaps the first really serious example of a homologation special – a bike designed to meet racing regulations firstly, be a road machine second, with production simply a necessary hurdle to make the bike eligible for what would become the World Superbike Championship one year later in 1988.

Sure, other firms had made race-special versions of production bikes, but the RC30 really shared nothing with other machines in Honda’s range and was more closely related to the RVF endurance racer than the VFR750F. Gear driven cams, a 360-degree crank, titanium con-rods and a single-sided swingarm set it apart from normal production machines. And the idea worked, taking Fred Merkel to the 1988 WSB title and Honda to the 1988 constructor’s championship, and doing the same again the following year.

While Honda initially intended to make only enough RC30s to satisfy the rule books, the bike turned out to be surprisingly popular despite costing twice as much as other superbikes. By the time production stopped in 1990, more than 4000 had been sold.

How ’bout an RC moniker?

Probably not. But more accurately, maybe. You see, the problems experience by the RC45 when it came to winning superbike titles came down to one thing; Ducati. The rules which allowed 1000cc twins to battle against 750cc fours seemed to favour the Italians, and Honda eventually followed suit with the VTR1000SP1 and SP2.

Under Honda’s internal naming convention, the VTR couldn’t be called RC since its capacity was over 899cc, and road-going bikes in that class were given SC codes rather than the ‘RC’ numbers that appear on 750-class models. (Meanwhile NC related to 400cc bikes, PC to 500s and 600s and MC to 250s.)

So the VTR1000SP’s internal name was SC45, with 45 simply being a sequential number in the sequence; it’s purely chance that it matched the number of the RC45. To add more confusion, in America the VTR1000SP was called the RC51, even though that wasn’t its real internal designation.

In case you’re not baffled enough already, Honda has independently used RC codenames on prototype racing bikes for decades, completely separately from its roadbike naming protocol. Hence we have GP legends like the RC174, RC149 and, of course, the more recent RC211, RC212 and RC213 machines. And we can’t forget the RC213V-S roadbike, which really shouldn’t qualify for the name since it’s not a race-only machine…

So since the new RVF will be a road-going model, with a capacity of 1000cc, it shouldn’t be called RC. But Honda has flouted its own naming rules before, so it would be no surprise if it does it again…

RINGING BELLS?

The emergence of the RVF comes on the heels of a long-running wrangle within Honda after its then-president announced in 2012 the firm would build a road-going MotoGP bike. At the time, he said: “Since its market introduction in 1987, the RC30 super sportsbike has been loved by a large number of fans. With a goal to create a new history, passionate Honda engineers have got together and have begun development of a new super sportsbike to which new technologies from MotoGP machines will be applied.”

While a road-going MotoGP machine had been mooted for years, and development work on such a machine had started, and stopped again, as long ago as 2003 when a road-going V5 RC211V was considered, the president’s speech meant there’d be no turning back.

DID YOU KNOW?

Despite no longer being available, the RC30 remained Honda’s top-line production racer for another three years until the RC45 appeared in 1994