Some motorcycles look like style icons. Some motorcycles look like they’re doing 100 kay an hour when they’re standing still. But the Böhmerland just looks like a barrel of laughs. Seeing Ernesto Mela’s Czech-built sidecar rig in action never fails to bring a huge grin to anyone’s face.

It was the same when a factory tester was about to demonstrate the power of Albin Liebisch’s long and low motorcycle by riding it to the top of Ještěd, the highest mountain peak in northern Czechoslovakia which stands 1012m high.

“If you make it to the top you’ll have to stay there – you won’t be able to turn around to come down!” shouted a spectator, much to the amusement of the crowd. Of course, the 600cc single romped up… and sailed back down again. It was another success in a series of climbs that Liebisch had devised to promote his new creation – although it is doubtful that he was impressed when people started calling it a motorised dachshund.

Sold under the Čechie trademark in Czechoslovakia and as the Böhmerland in Germany (both meaning Bohemia), they were the longest production motorcycles ever to roll out of a factory. Measuring 3180mm from front wheel to rear luggage box these were never going to be nimble machines that would set a racetrack alight, and that must have been a surprise to anyone who knew the man who provided the capital for Liebisch to set up shop.

Wealthy textile manufacturer Alfred Hielle was a Polish-born petrol head who had known Ettore Bugatti since 1903 and even helped finance his car factory in Mosheim in the Alsace region of what is now France. Hielle also raced Bugattis and imported them to Czechoslovakia where he fitted his own bodies. And he rode motorcycles with flair.

The textile industry was never going to be enough for Hielle and in 1923 he founded his own automobile company in Krásná Lípa, a small town 100km north of Prague and 5km from the German border – it was known as Schönlinde in Germany. Besides importing Bugattis, Hielle began manufacturing trucks. Liebisch saw an opportunity to improve his prospects and joined the new company. When Hielle went on a promotional tour of Europe, Liebisch joined him to share the driving and the two became good friends and it was probably on this trip that they came up with the idea of a motorcycle that would be cheaper than a car, but still capable of carrying three people in style – without a sidecar.

Most new motorcycle manufacturers outsourced engines, but Liebisch had other ideas and he got straight to work. He designed a 600cc overhead-valve engine with a bore and stroke of 79.8 x 120mm, dimensions remarkably close to the Model 19 Norton that had performed so well in the 1923 Isle of Man Sidecar TT. Like the Norton, the rockers used inverted cups to locate the pushrods. It was a strange idea because the lubricating grease always ran out when the engine got hot. At least Liebisch fitted nickel plated caps to keep the oil that lubricated the caged needle rollers inside the rocker arms. A hemispherical cylinder head was used along with an alloy piston, while to reduce the weight seven holes were bored through the H-section connecting rod. Power output was 16hp at 3000rpm, with impressive torque.

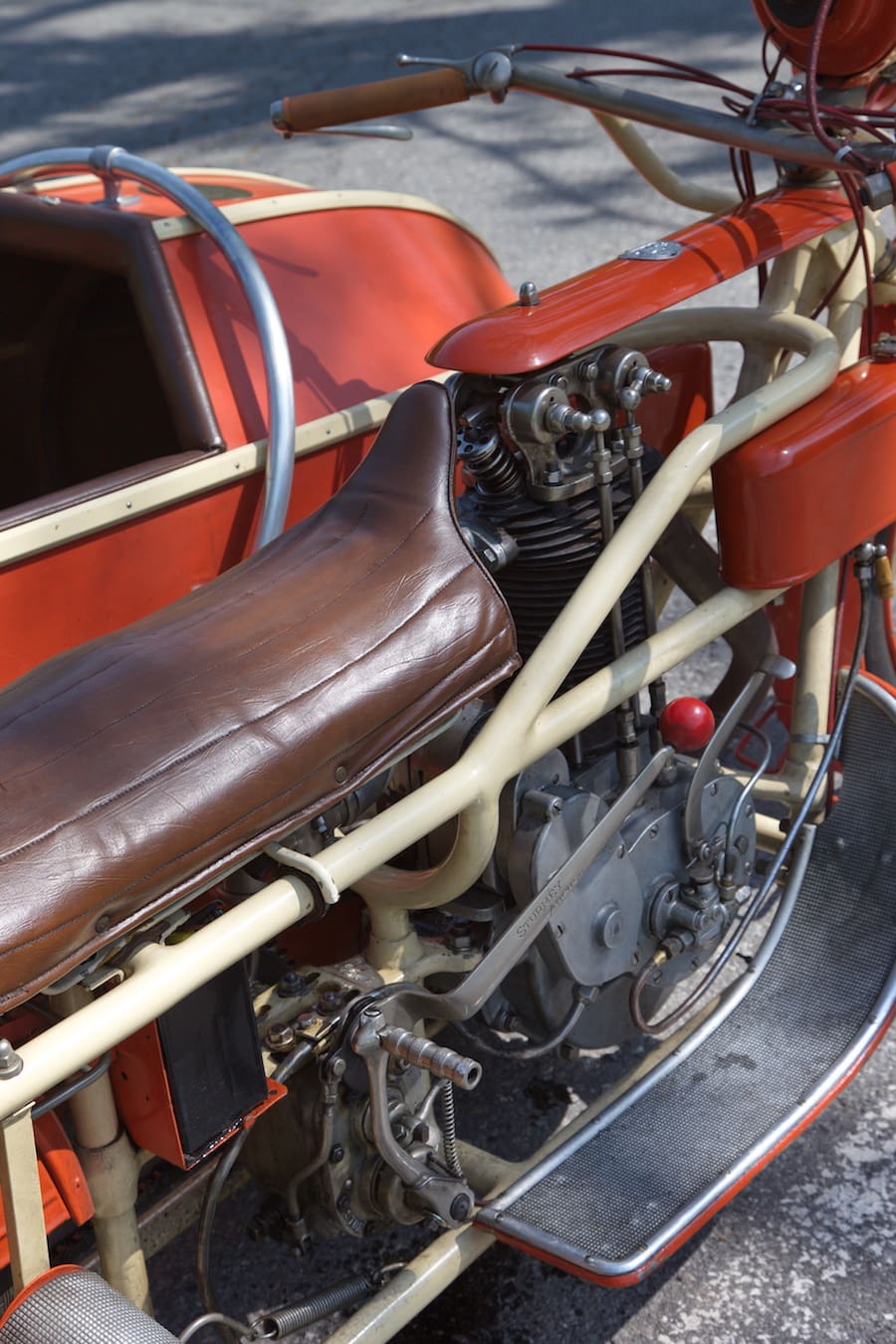

While the British bike used a chain to drive a forward-mounted magneto, Liebisch’s engine featured a gear-driven Bosch Type FF1 mounted behind the cylinder barrel. A Michalk oil pump that was clearly based on a Best and Lloyd was screwed to the timing chest and driven from the inlet cam, while the AMAC carburettor was mounted on a steeply updraft inlet stub. Liebisch also shopped in England for a heavyweight three-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox, although the German-made Hurth gearbox would later be an option.

In the early 1920s most motorcycles used a frame that hadn’t progressed much beyond the bicycle, but not the Böhmerland. Liebisch designed a full-loop twin-tube cradle chassis, with a forging for the headstock and welding for the rest of the joints that was so neat it would have impressed legendary frame builder Ken Sprayson. A centrestand with a return spring was standard fitment.

The leading-link fork, with adjustable damping and two long springs under tension instead of the more common compression, was also designed by Liebisch. Fuel was carried in twin cigar-shaped tanks mounted either side of the rear wheel, each holding five litres. The oil tank, mounted at the front of the frame on the right side, held 2.5 litres. A matching toolbox was on the left, with a large pressed steel luggage box suspended from the back of the frame, behind the wheel. Because there was no conventional petrol tank, there was a strong probability that the rider’s lap would be splattered with oil and so the long, dual seat tipped up at the nose to create a splash guard. A third seat was mounted over the rear wheel. And what wheels!

Liebisch also pioneered the use of lightweight alloy wheels on a motorcycle. Aluminium wheels had been premiered by Ettore Bugatti on his Type 35 racer in 1924. These eight-spoke wheels featured a detachable rim, secured by 24 screws. Besides being lighter than a wire-spoked wheel they also looked elegant. There is little doubt where Liebisch got the idea for alloy wheels from, but he used a much stronger one-piece casting with strengthening webs. There were six holes in the disc to make them lighter, and they incorporated a ribbed cast iron brake drum. Like the chassis and steel pressings, the wheels were finished in Duco-Du-Pont, a quick-drying enamel favoured by American automobile manufacturers. The prototype Böhmerland was ready for the road in 1925 and production versions went on sale a year later. All motorcycles would be hand built to order, with only very minor differences throughout the production run. Most would be finished in a combination of green or red for the mudguards and tanks, with cream or yellow for the frame and wheels. Of course, with many motorcycles being built to order, other colour options were available.

In 1927 Liebisch started manufacturing sidecars but he must have been hooked on the ‘solo motorcycle people carrier’ because that year he offered an even longer version of the 600cc single. The Extra Long Model featured an extended frame and a bench seat for three, with the solo saddle on the rear carrier meaning that four adults could be transported in some style – although negotiating tight corners would have proved interesting. A third petrol tank was fitted above the engine. The Extra Long even came with a second Sturmey-Archer gearbox mounted directly behind the first, to make six gears available. An ultra-low ratio could be selected for hillclimbing and slow-speed manoeuvrability. One gearbox lever was positioned in front of the rider and one behind him, so he risked becoming over-familiar with his nearest passenger if he wasn’t careful. Records show that only three Extra Long Models were built, and one of these is still regularly ridden in Czechoslovakia.

When Hielle decided to sell his estate in Krásná Lípa he didn’t desert his friend. In 1931 Hielle helped Liebisch buy a small factory in Kunratice, near Šluknov, where production continued until 1939. Estimates vary, but between 800 and 1500 Čechie and Böhmerland were built and about 70 are known to survive, only 40 of which are on the road. And that makes Ernesto Mela’s Böhmerland rather special.

When his sidecar outfit rolled out of the Schönlinde factory in 1928 it came with the optional Bosch 100-watt Magdynamo, 30-watt headlight and an electric horn. A narrow pressed steel guard over the cylinder head was also fitted to keep most of the oil off the rider’s crotch. After tickling the AMAC and setting the ignition advance with the lever on the left side of the handlebar, he depresses the long pedal on the timing chest. This lifts the exhaust valve so that he can spin the long-stroke engine over quickly when he kickstarts the beast. With the throttle levers set just-so, a single kick has the Böhmerland chuffing into life. And then he’s off, changing up at about 25 and 40km/h before snicking into top.

“Loaded with four adults acting like big kids it will do about 88km/h if I push it,” says Ernesto. “But 65km/h is plenty. At that speed the brakes will still keep you out of trouble.”

The long wheelbase isn’t really a problem on a sidecar outfit, but it might be on a solo and he sympathises with the factory rider who rode to the top of the mountain. “You need a lot of space to turn around in a narrow road,” explains Ernesto. “I usually have passengers who can help me by pushing the outfit backwards…”

It might not be the fastest bike in the world, and it isn’t the easiest to manoeuvre. But there are advantages. “It’s easy to make friends when you have a Böhmerland,” says Ernesto. “Everyone wants a ride!”

Words Phillip Tooth Photography PT & Städtische Museen Zittau