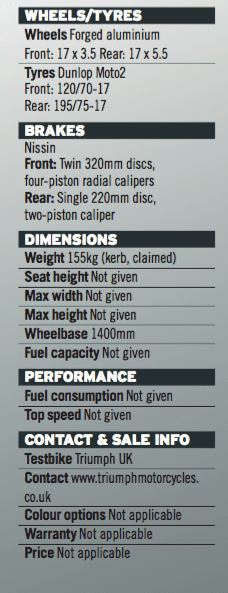

When news broke that Triumph was set to replace Honda as the control engine supplier for Moto2 with a specially tuned version of its then-new 765cc triple, eyebrows were raised around the world, followed by wide grins. It meant that from 2019 onwards the no-holds warfare that is Moto2 will play to a new soundtrack, with Honda’s high-revving four-cylinder 600cc screamers replaced by the glorious mellifluous howl of a herd of open-pipe three-cylinder racers. It’s a triple treat that hasn’t been heard on a racetrack for the best part of 50 years, ever since Giacomo Agostini scored successive GP worlds on the three-cylinder MV Agusta machinery in the early 1970s.

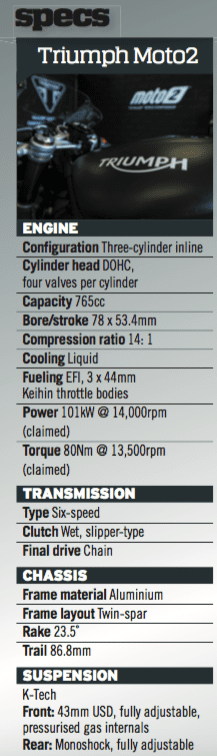

It’s the biggest shake up to the intermediate class since Moto2 replaced 250cc two-strokes in 2010. Not only will the larger-capacity engine be more powerful and offer a heap more torque than the outgoing Honda, but the class will run traction control and clutchless downshift autoblippers for the first time. The arrangement will see the British manufacturer provide around 200 engines annually for the class, similar to what Honda currently furnishes for a full grid of 32-34 riders, together with the supply of components to Dorna subsidiary ExternPro who refreshes each motor after every three rounds.

Headed by one-time HRC race engineer (and Nicky Hayden’s former crew chief) Trevor Morris, ExternPro took over Moto2 engine preparation at the end of the 2012 season, and will be responsible for supplying a new or reconditioned Triumph powerplant to each Moto2 rider. Currently, the engines are reconditioned with a new crankshaft, pistons and rods after three GPs before being re-allocated via a lottery system. All engines are numbered, with a detailed record available for each, and they’re each sealed. ExternPro’s contract allows a three percent variation in peak power of just under 130hp – but the company’s attention to detail has helped them reduce that difference to around one percent.

To be anointed as Dorna’s partner in taking the Moto2 category up a level in terms of performance and sophistication next season, Triumph had to overcome rival bids from several other manufacturers with established links to MotoGP – KTM, Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki are all believed to have tendered for the deal. But the British manufacturer clinched it, and Triumph’s R&D team has spent the past 18 months developing the engine, and evaluating the result on track mounted in a 2013 Daytona 675 test mule ridden by 2009 125cc world champ Julián Simón.

At Aragon in June this year, the engines finally matched for the first time on track with Magneti Marelli’s customisable control ECUs, and three key chassis manufacturers (Kalex, KTM and NTS) ran the Triumph engine for the first time in their 2019 frames. That left the Daytona test mule fitted with Triumph’s stock Keihin ECU surplus to requirements. And that’s where I came in. Let loose on Silverstone’s short 1.74km Stowe circuit to sample the fruits of Triumph chief engineer Stuart Wood and his R&D team’s efforts in producing a mechanical gamechanger for the Moto2 category from next year onwards.

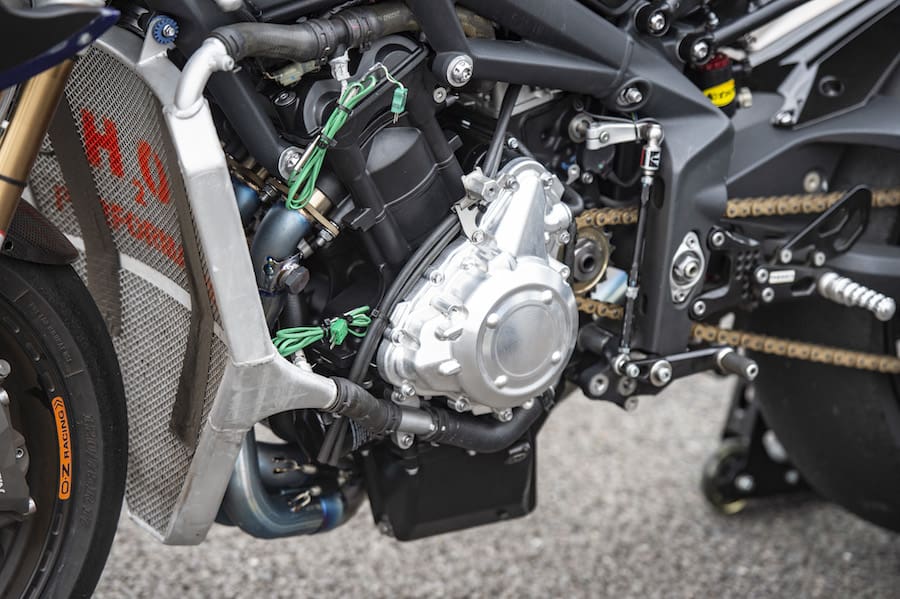

To do this, they’ve retained the stock 765 engine castings, including the Nikasil-lined cylinder block, and modified the internals – though surprisingly not as much as you might expect.

“We’d agreed with Dorna to use our new, larger-capacity 765 three-cylinder motor, and we knew what we wanted to do with it, which was to get more power and more torque out of the engine compared to the standard streetbike,” Triumph’s Chief Product Manager Steve Sargent said. “To do that, we needed to spin the engine up faster and reduce the inertia within it.” This meant removing superfluous items like the starter motor, then comprehensively re-porting and gas-flowing the cylinder head to allow the engine to breathe even better. They fitted lighter titanium valves which are the same size as in the street engine but with stiffer springs, and race camshafts with higher lift and greater duration on the valve timing.

The shape of the combustion chamber is essentially unchanged, but compression has been raised to 14:1 from 12.65:1 on the stock RS by skimming the head, and with a lighter, low-output race alternator which Sargent says makes a big difference in reducing inertia. There are revised engine covers to reduce the engine’s width, as well as a different cast-alloy engine sump to permit a more tucked in run for the 3-1 Arrow titanium exhaust’s headers.

The standard crankshaft, counterbalancer, conrods and cast three-ring pistons are all retained in unmodified form – so the crank hasn’t been lightened – but a close-ratio six-speed gearbox has been created by fitting a taller ratio first gear and a slightly shorter second gear, while the upper four ratios stay the same as the roadbike. It’s worth noting that Moto2 teams aren’t allowed to change the internal ratios of the gearbox, nor the primary drive, which is also standard, but the race-developed slipper clutch now fitted is tuneable. The stock offset chain drive to the cams has been retained, rather than gears, and the rev ceiling’s been raised from 12,650rpm on the road bike, to 14,000rpm – an impressive demonstration of the engine’s robustness.

The result delivers what Sargent confines himself to stating is “over 135 horsepower” at 14,000rpm versus the 765RS’s 123hp at 11,700rpm, with 80Nm of torque at 13,500rpm versus 77Nm at 10,800rpm on the RS. But whereas the 765RS figures are taken at the crankshaft, Sargent declares the Moto2 readings to be taken at the gearbox, or on a dyno.

But the improved performance is even greater than it appears on paper – and that was very quickly apparent during my squirt around Stowe where a true fourth gear is as best you’ll get.

Read the full story in AMCN Magazine Vol 68 No 09

TEST ALAN CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY KEL EDGE