With the Great Depression looming in 1929, Jack Bowers saw nothing but tough times ahead and decided that the best way to beat the looming downturn was to head bush with close mate Frank Smith.

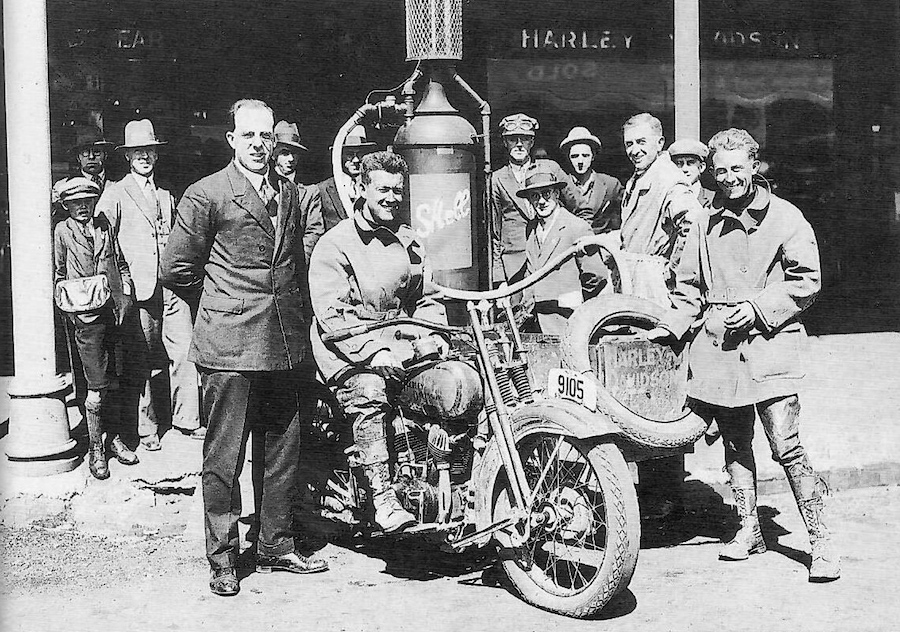

At 128 quid, a Harley-Davidson magneto model with sidecar chassis was no steal, but distributors Bennett & Wood threw in free pullovers for the intrepid lads and the deal was done.

Using hardwood, the boys constructed a coffin-like box, the bottom of which was a petrol tank from a Model T Ford. Spare tyres were secured on either end and mild steel brackets straddled the luggage rack over galvanised-iron water tanks. On top was their camping gear.

Catering was by means of a 12-gauge shotgun and a repeating Winchester mounted on the side of the coffin. And while the provisions included a Browning pistol, there’s no record of gelignite.

On a test run, the duo found the outfit considerably undersprung.

It was Independence Day in 1929 when, with a grand total of 60 quid in the money belt, Jack and Frank rolled north from Sydney to lap Australia. Day after day, from sun up to sundown, they battled on, and were well into western Queensland before suffering tyre problems. With what must have been close to half a tonne of iron and hardwood bearing down on the vulcanised Dunlops, it’s a wonder anything on the outfit was still serviceable.

Tyre troubles aside, they’d covered almost 3000km, with only 13,000km to go. The scenery was fantastic. Every meal a culinary delight, flapjacks made with plain flour and bi-carb of soda with treacle, and a cuppa shared with the ever-present flies.

The petrol ran out 15 kays from Camooweal, some time after the water had been depleted. Frank elected to walk to town. Figuring that anyone headed to where he’d left Jack would make the pub their last port of call, Frank settled in for a drink. Miffed at paying two bob for a beer, Frank returned alone, and some time passed before he sighted Jack’s campfire. As neither owned a watch, their guess was that Frank had taken about nine hours. And had returned without water.

“I had a beer in town before I left”, said Frank. “And I’m thirsty”.

“So am I!” replied Jack.

Days later, the pair were waylaid at The Coongan Hotel.

“The proprietor suggested we might have a drink with him,” Jack said later. “He later suggested we have a drink with his wife, and some time later we also had a drink with his boxing cat, as well as drinking with various other objects of less material value.

“Several hours later we steered an unsteady course for our machine and made an equally unsteady departure. This was indeed a most pleasant day and we sped on in happy spirit. We were almost to the point of breaking into song as the wind rushed pleasantly past our happy faces. Life was really worth living.”

However troubles lay ahead. The sidecar chassis was cracked and there was an ominous knocking from the motor. It’s not at all difficult to tell when a conrod is broken – particularly when you’ve got one half in your right hand and the other in your left.

The homesteads they’d passed had all been abandoned because of the drought, and they were still 480km from Adelaide. The next homestead, however, was occupied.

The owner was happy to supply food, lodgings and the use of his machinery shed. And wonder of wonders, the shed contained a derelict sidecar, the wheel of which, with some modification, fitted the Harley.

At last there was a semblance of a road and they finally wobbled through Adelaide and headed for Melbourne.

The local motorcycle agents, Milledge Bros, were now behind the duo’s efforts and offered support and encouragement, even springing for a hotel room in the Victorian capital.

Heading to Sydney, Frank remarked on the vast number of swaggies on the road, the numbers confirming the fears they’d had about the coming depression.

But Jack and Frank returned in triumph. With the stamping of their Auto Cycle Union card at Sydney GPO on 21 September 1929, they were not only the first to circumnavigate the continent on a motorcycle and sidecar, but set a new record for any motorised vehicle.

And, as Jack put it, “also dispelled all doubts those cautious potential sponsors had had about man not being able to live with man for long periods in isolation.

“We really felt as though we had achieved something.”

By Peter Whitaker