Twenty six years on, the magic of it still thrills the spirit – especially in the memory of those privileged to have witnessed it personally. The closest, fastest, most exciting and most enthralling Isle of Man Senior TT ever run resulted in a long-awaited all-British victory for super-Scot Steve Hislop and the Norton rotary.

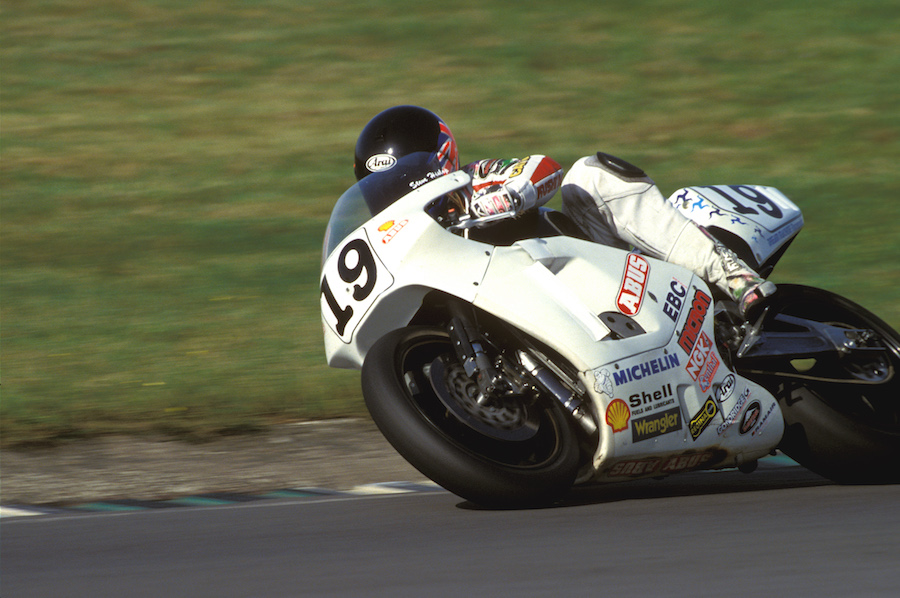

It was painted an unaccustomed white to reflect the support of Steve’s personal sponsor ABUS, rather than the usual black of Norton’s mainland cigarette sponsors, John Player Special. You can bet when they heard the result, JPS management must have kicked themselves for not finding the extra budget to support Norton’s quixotic, shoestring assault on Japanese supremacy in the world’s oldest and most famous road race.

To win the 1992 Senior TT, Hislop had to contend with not only the perennial Honda threat, led by factory-supported Honda Britain rider Phil McCallen and TT maestro Joey Dunlop, but with another graduate – like himself – of the Honda school of TT talent, future four-time World Superbike champion Carl Fogarty, who later that same year would clinch the 1992 World Endurance title. Only, like Hislop, Carl wasn’t riding a Honda this time either, but instead a tricked-out Yamaha.

And then there was his teammate, Joey’s kid brother Robert, riding a rotary racer he’d leased for the event – and running in JPS colours.

The pace was electrifying from the start, with the lead see-sawing between Fogarty and Hislop, who were never more than eight seconds apart on corrected time throughout the six-lap race.

The ABUS Norton rider lost time at his second fuel stop, with a filler cap that wouldn’t close, leaving him three seconds behind the Yamaha at Glen Helen on the penultimate lap. But a superhuman effort saw him retake the lead by six seconds starting the final 37.73-mile lap, in which both riders broke the outright lap record, Fogarty leaving it at 123.61mph. But it wasn’t enough; he was just 4.4sec away at the flag.

Norton had won its first IoM TT race since 1973, when Peter Williams took victory in the F750 race on the monocoque John Player Norton.

Compared to Ron Haslam’s short-circuit bike, which I also rode the same day at Snetterton in eastern England, the Hislop machine couldn’t be more different. Even running roughly the same settings he had used in the IoM, it was like the difference between a GP racer and a (very powerful!) roadbike. Haslam’s felt just like what it was – a Rotary racer set up like a 500GP bike for a rider who’d spent the past decade riding such machines on purpose-built circuits at World Championship level.

“To be honest, the first time I rode the Norton in TT practice, I thought I’d made a terrible mistake,” Hislop once told me ruefully. “The way Ron had it set up was completely unsuitable for the Island, and it was actually quite a battle to persuade the team that it had to be altered drastically to make it rideable at race-winning speeds there. But I got my way in the end – just as well, really!”

Too right. Basically, Steve needed a much softer set-up and a higher ride height, which I noticed immediately sitting on his Norton in the pits at Snetterton – it was measurably taller off the ground than Haslam’s and, with a 50mm-longer wheelbase, it was also much more stable through the fast sweepers.

On the other hand, the longer wheelbase meant it didn’t wheelie quite as easily out of turns, and traction was better out of slower turns under something approaching full power. Parliament Square, Ramsey Hairpin, Waterworks, the Gooseneck were all easy meat for the ABUS Norton in TT mode, especially with that lovely, linear power delivery from the twin-rotor engine.

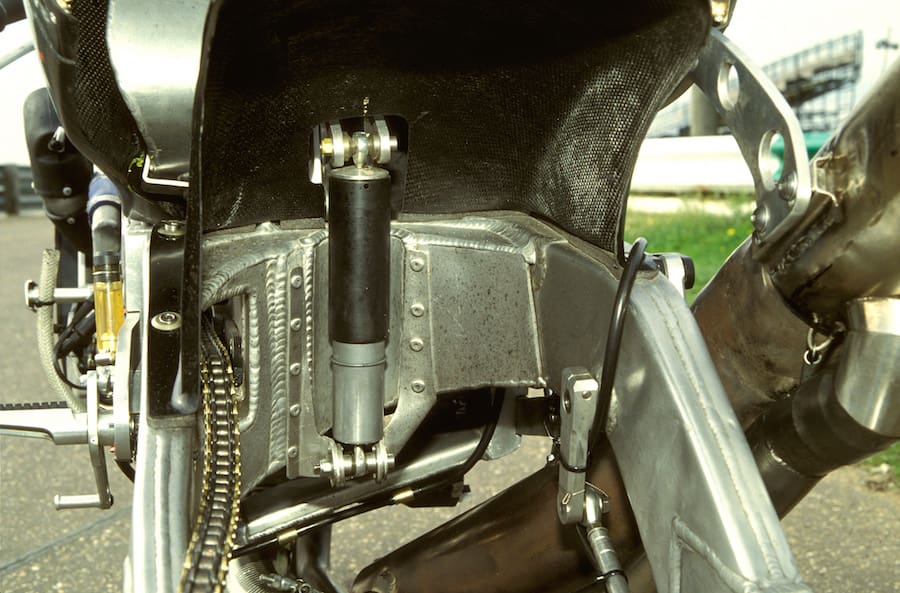

Another factor in the improved traction may well have been the auxiliary damper unit that Maxton’s Ron Williams had grafted onto the modified Koni rear shock for 1992.

“The problem was the inherent surge of the rotary engine running on a closed throttle,” Haslam explained. “When that happens the engine speed varies, which loads the gearbox and winds up the rear shock, then unloads it again. By using an additional damper unit that comes into play after about 40mm of travel on the main shock, we can control this unusual problem.

“On a bumpy circuit like the Isle of Man, the second damper comes in earlier to stop the rear end squatting too much, which improves traction, so there’s a double benefit.”

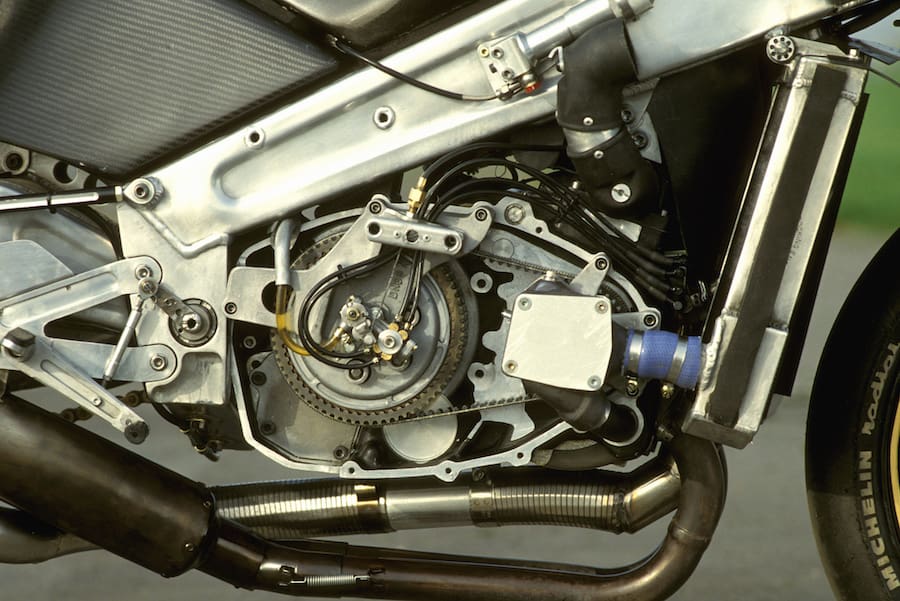

As different as the two set-ups were, both Nortons had one thing in common – the twin-rotor engine’s liquid-smooth power delivery and unbelievably meaty torque at almost any point in the rev range. It was surely one of the great motorcycle power units of its era in racing form.

The team refined the engine considerably during the 1992 season, fitting bigger 37mm Keihin flatslides, which gave a very immediate but still controllable response and helped unlock the waves of torque in the motor at almost any point between 6000rpm and the 11,500rpm rev-limiter.

The biggest difference, though, was the power delivery. Although power rose to 110kW (147hp) at 10,000rpm for 1992, it was actually more linear and progressive than on the ’91 bike, which was much peakier. Just twist the wrist, at almost any revs in almost any gear, and the Norton delivered. What a great Island engine.

Read the full story in AMCN issue Vol 67 No 23

TEST Alan Cathcart

PHOTOGRAPHY Kyoichi Nakamura