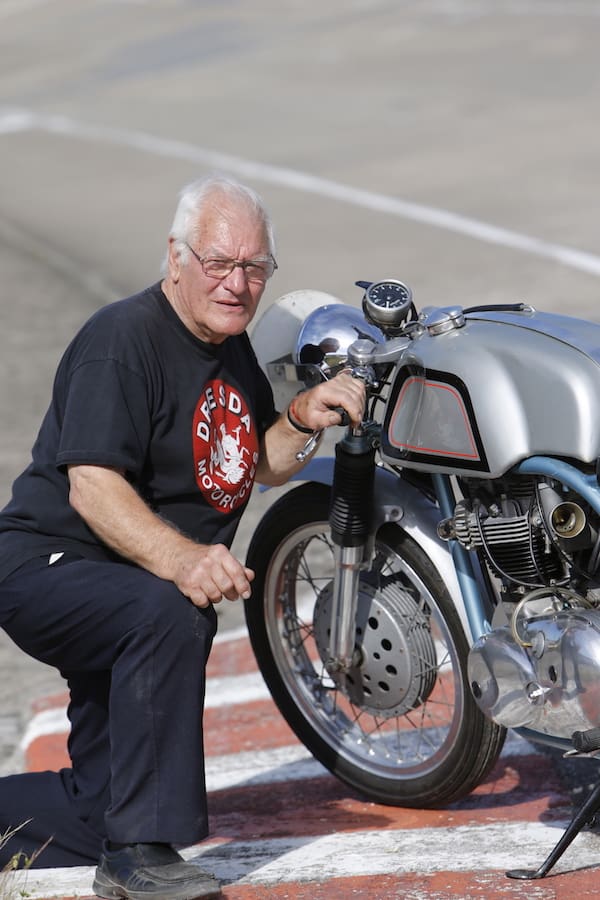

Dave Degens looks back at the pair of Dresda racers parked on the Montlhéry banking and says: “I never really liked riding here – I crashed in 1970 when I was blinded by the sun when I was right at the top. I hit the rail and came off. But Montjuïc Park, that was tight and twisty. The sort of track that was designed for a scratcher like me,” he grinned.

Only 3.78km long, Montjuïc Park was home to the Spanish Grand Prix. The anti-clockwise street circuit climbed the highest hill in Barcelona, and riders had to contend with a steep descent, numerous hairpins and a roundabout. It was also the home of the Barcelona 24-Hours race.

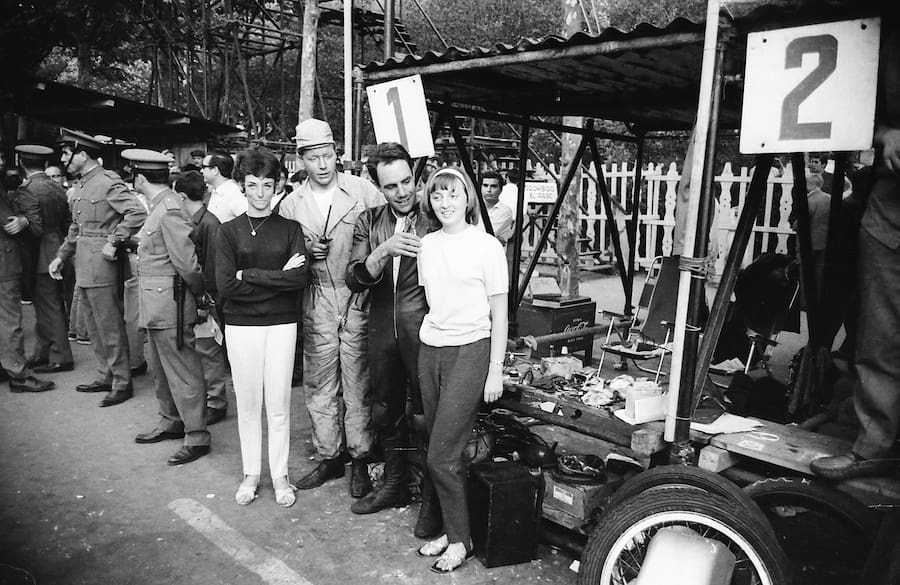

Degens had ridden an Earles-forked 600cc BMW R69S at Montjuïc Park in 1964. It was prepared by West London main agent MLG, one of whose riders dropped out of the 24-Hours just two weeks before the race. Degens received a call asking if he would partner Ginger Payne. He wondered why they wanted him, but Ginger told it straight – he recommended him because he was the toughest rider he had ever raced against.

During practice, Degens was much quicker in the night sessions, so volunteered to do the maximum of three hours followed by a 30-minute rest when it got dark. Payne was supposed to make up his hours after the sun rose.

“But he wasn’t much quicker in the daytime,” Degens laughs. “I was 24 and fit – I ended up riding for about 18 hours! There were plenty of Montesa, Ossa, Bultaco and Ducati bikes there – the track was ideal for nimble lightweights – but there were a few English teams as well. Velocettes were having the usual problems with clutches and primary chains, and of course there were Triumphs and Nortons.”

But there was no fairytale ending to Degens’s Montjuïc Park debut.

“It was disastrous! It was too easy to ground the heads on the long downhill left-hander, so I had to keep the bike upright and hang out to stop it dragging on the road. It was a bit of a plodder and a bit lollopy – it certainly wasn’t a short-circuit bike. The generator packed up, and towards the end I lost third gear.”

The race was almost over when the BMW stopped with a broken rocker – again.

“The rule was that you had to push it to the pits within three minutes. If I had broken down on the right side of the hill I could have glided home but the engine stopped before I got to the top and had to push it over. It took me five minutes.”

But sometimes from adversity comes ingenuity, and it gave him an idea.

“If I used a Manx Norton Featherbed chassis to give me the handling and a Triumph engine for performance and reliability, I could build a bike that could win this race.”

Degens returned to England firing with determination. And he had help from an unlikely source; the director of the endurance race was so impressed with Degens’ performance on the BMW that he invited him back for 1965.

“He offered me enough start money travel to Barcelona, do the race and still have enough left over for two weeks’ holiday in Spain!” he laughs.

Instead of choosing one of the new unit-construction Bonneville engines, Degens decided to build a pre-unit T120 from new parts.

He opened the inlet ports to 30mm and fitted Bonnie racing cams and followers, with standard valves but stronger springs. The timing gears were lightened, polished and balanced, and the idler pinion fitted with a needle roller bearing.

Triumph had changed over to Hepolite pistons, but Degens fitted Wellworthy units and instead of twin Amal GPs, he bought a pair of 13/16-inch Monobloc carbs. He had the crank assembly tuned to a factor of 85 per cent and, after he spoke of his project to the Lucas race rep, he was given a specially built magneto.

“When I was racing Manx Nortons I had to carry spare gears because they were always giving trouble, but I never had problems with a close-ratio Triumph ’box, so that’s what I used.”

A duplex chain primary drive came from a 1965 unit-construction engine while the gearbox was a 1962 component.

Generator failure was a common problem in the 24-Hours, but he still fitted a new concave Cibie Type 22 headlight unit with a 55-watt iodine vapour bulb that was supplied by the sales rep, along with the promise of a bonus if he won.

His father machined the rotor of the 80-watt, 12-volt Lucas alternator to give more clearance. This reduced performance – but also drag, which cut the losses in engine power – and was good enough to keep the batteries charged. And he had another trick up his sleeve: “I thought, instead of stopping and repairing a generator, I’d fit two batteries, one each side of the seat. And I’d have another four on charge in the pit. We could change them over when we swapped riders.”

Degens bought the frame, but the Barcelona Triton never had its own wheels or petrol tank: “I borrowed them from my co-rider, Rex Butcher, who pulled them off his Manx. I wanted Rex with me because he was a good friend… and I’d never seen him fall off!”

The rear stopper was standard Manx, but the front brake was a twin leading shoe Oldani. “All the top racers including Hailwood and Minter liked the Oldani because it was a bigger diameter and had wider shoes.”

Both the petrol and oil tanks were pure Manx, but the silencer was from a BSA Gold Star. “It was the most efficient silencer you could buy. It was designed to perform like a racing megaphone. Even when Triumph produced the Thruxton race version of the Bonnie they used a silencer based on the Goldie’s.”

To speed up wheel changes, Degens thinned down the spindle nuts and welded on tommy bars. “I could change the back wheel in less than two minutes, although the front wheel took a little longer,” he recalls.

There was no name on the Norton tank, but the Dresda was instantly recognisable by the handsome metallic light-blue paint on the frame.During practice the engine started pinging.

“We had to use petrol supplied by the organisers.

It was quite a low octane rating – fine for the Spanish strokers, but not much good to me. I had to fit two cylinder-head gaskets to lower the compression.”

His father had worked out that if he lapped consistently at 2m10sec they would be fast enough to win. “But that was too slow for safety. We needed to go a bit faster to stay focused.”

A Bonneville campaigned by Mike Chatterton and George Collis led for the first six laps before the Dresda Triton moved in front for half an hour. But the pace was too hot for Mike’s unit-construction Bonnie, which holed a piston when he tried to take the lead again.

After six hours’ racing, the Dresda Triton pitted for lights – Dave didn’t fit a switch because it was one less component that could fail. “That’s when the Sirera brothers’ Montesa moved in front,” says Dave. “We were happy to stay in third or fourth place for a while. I wasn’t going to risk a blow-up.”

Dave and Rex would swap places every two hours, although neither would get much sleep in their rest period. About half-way through, the Dresda pitted with a rear puncture, but Jorge Sirera came off when his front tyre punctured. Dave and Rex had honed their race skills on England’s short circuits, learning how and when to overtake, and how to take advantage of the weaknesses in another rider’s style. They might have had fast bikes, but the Brits were hustling them.

“We liked to make them think that we were going quicker than we were, so that they went quicker than they wanted to,” says Dave. “The Dresda would get airborne just before a tight hairpin – there are six on the downhill stretch before the fountain,” explains Dave. “Rex and I could brake after we landed and make it around, but it looked scary and nobody else could do it. It freaked the Spanish out!” Eventually, the Spanish leaders blew a crankcase seal.

“But we always kept 500rpm in hand.”

The Ducati factory had put up a cash prize for anyone who broke the record it had set the previous year, but it wasn’t ready for the Dresda, which looked like it was going to take the money.

“Then the tube at the end of my silencer broke off,” says Dave. “Ducati protested I was running with a racing megaphone and the scrutineers called me into the pits. I was in the clear because it was a two-into-one and the volume was smaller than the maximum allowed. But they still made us swap it for a straight-through pipe. That protest cost me five or six laps!”

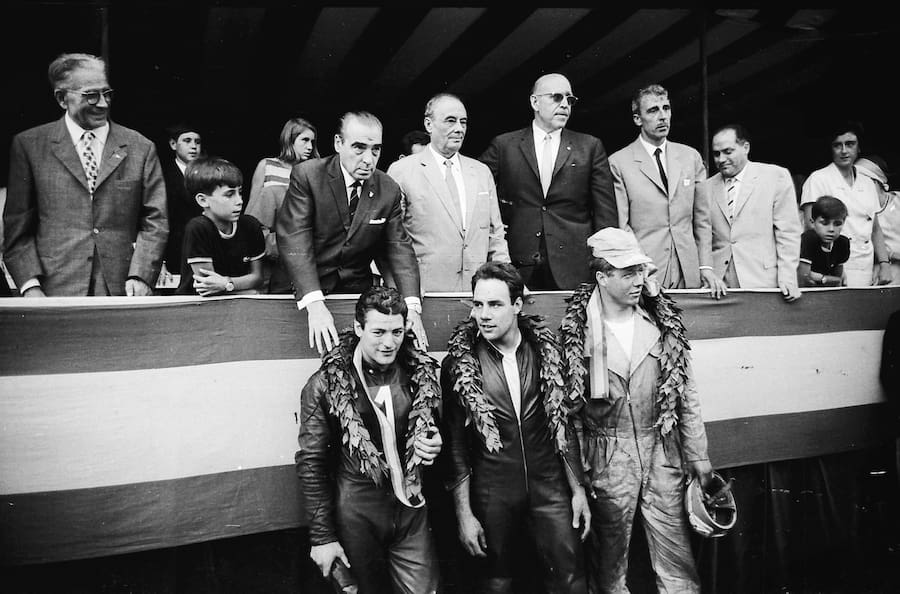

With six hours to go and seven laps in hand the Dresda came in for a quick oil change and chain tension. “The Velocette was running like a train in second place for ages until the clutch let them down,” recalls Dave. At the end of the 24-Hours, the Dresda team had covered 2386.41km during 631 laps, three more than the best works Montesa and six more than the Velocette. Spanish two-strokes filled the following five places.

“The chain was so worn out that it was almost dragging on the road,” remembers Dave. “We fitted a new one at half-time, but that was knackered by the end as well.” And the brake shoes wore through to the rivets. “For the last hour or so I could feel the brake grinding, but we were so far in front that I didn’t have to ride that quickly.”

Dave was back in Barcelona for the 1970 24-Hours – but this time it would be on a bike with his own chassis. “I used to race a 500cc Daytona engine in a Norton chassis for Allen Dudley Ward. It was a good engine but the frame was too heavy. I needed something lighter,” he says. Dave had set the 350cc lap record at Brands Hatch on an Aermacchi, and his father timed him on different sections. “Dad said I was a second quicker around the hairpin and up to Clearways than I was on any other bike – even the Dresda Triton and the

Domiracer. So, I made my own duplex frame using the Aermacchi dimensions.”

First time out, at Snetterton, he was dicing for the lead with Percy Tait on the factory Triumph.

“My bike accelerated quicker out of corners because it was lighter, but he was a shade faster, so he would slipstream me on the straights then nip in front. Percy just beat me, but at my next outing at the Scarborough International I won the prestigious Gold Cup.”

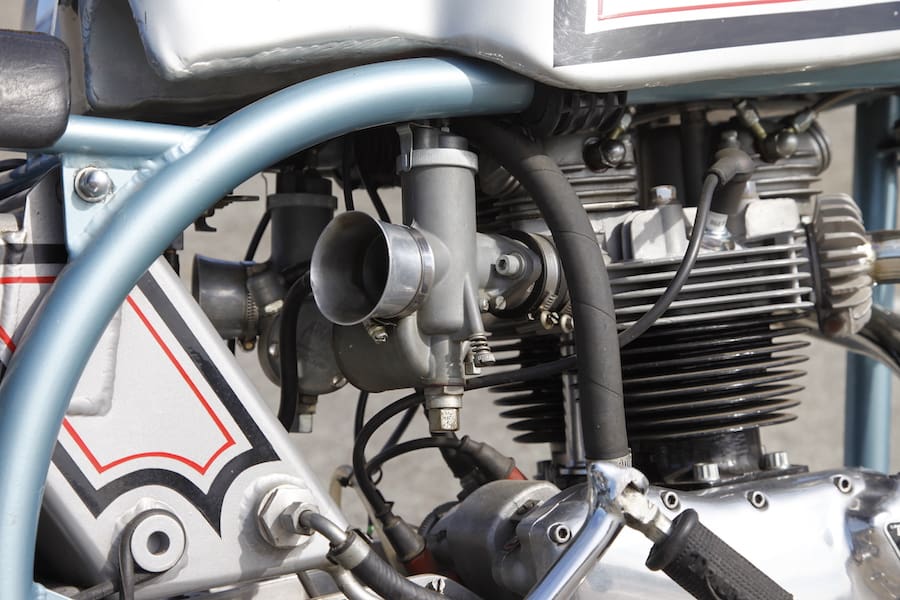

He soon realised he could squeeze a 650cc engine into his Dresda frame and decided to build a bike that could win the 24-Hours again. The crankshaft and conrods were polished, he lightened the camshaft and timing pinions and carefully matched the pistons and rings. The cams were nitrided to make them tougher, a set of Dresda off-set rockers increased the lift while maintaining stock timing, and the inlet ports were opened out to match the 32mm Amal Concentrics. He also fitted central spark plugs.

“With a high-domed piston and a spark plug on the side, the explosion pushes the piston away as well as down,” says Dave. “It can cost you 200rpm.”

He designed his own fork, with the fork-leg lower acting as a bush for the chrome-plated stanchion, and also designed the front brake with John Cerhan, a Hungarian refugee who worked at Dresda.

“We tried a 12-leading shoe in an eight-inch drum first, but it got too hot! We settled on an eight-leading shoe brake in a much bigger drum.” Although the petrol tank looks like the one fitted to his short-circuit bikes the capacity is substantially more and the fairing and straight-through exhausts were rubber mounted.

“The front end would lift coming out of the hairpin at Mallory so I lengthened the swingarm by an inch,” says Dave. The last thing to do was to again fit a second head gasket to reduce the compression. That still gave him 56hp at 6700rpm, with another 500rpm in hand.

“We were up against a lot of good teams,” recalls Dave. “The Kuhn bikes had Seeley frames, with Barry Sheene and Pat Mahoney pairing on one and Tom Dickie and Ron Wittich on the other. We thought they would be the ones to beat.”

Wittich took the lead for the first hour before being told to slow down. He and Tom were still leading four hours later when the exhaust pipe fractured soon after dawn, digging into the track and dumping Dickie on the deck. This left Bob Heath/Nigel Rollason in front on a BSA 500cc single, one lap ahead of Sheene/Mahoney. Rollason crashed twice before the Beesa was sidelined by ignition trouble after nine hours.

“Barry was a good friend but I still pushed him into thinking that he had to ride faster than he needed to,” says Dave. After 15 hours, the second Kuhn Norton’s gearbox broke. “When I spoke to Barry in the pits he was physically exhausted,” Dave recalls. “He said he couldn’t have lasted for 24 hours and was glad that the bike had packed up.”

Degens and Goddard moved to the front after 18 hours. “The engine ran faultlessly!”

While the Honda 750s ate brake pads the eight-shoe stopper only needed adjusting three times. And while some competitors were tensioning and changing drive chains, the Dresda’s swingarm geometry meant that the chain needed adjusting only once. Ridden hard, the Triumph engine was averaging over 40mpg (5.8L/100km) but towards the end of the race, with a comfortable lead and

the revs dropped to 6000rpm, they got over 50mpg (4.7L/100km).

Team Dresda won handsomely, covering 656 laps in the 24 hours. A Bonnie claimed second place 11 laps down, while the best Honda CB750 was 14 laps adrift. There were 25 finishers from 50 starters. Not bad for a bike designed and built in a small shop in Putney.

Words Phillip Tooth Photography Xavier Roca& PT