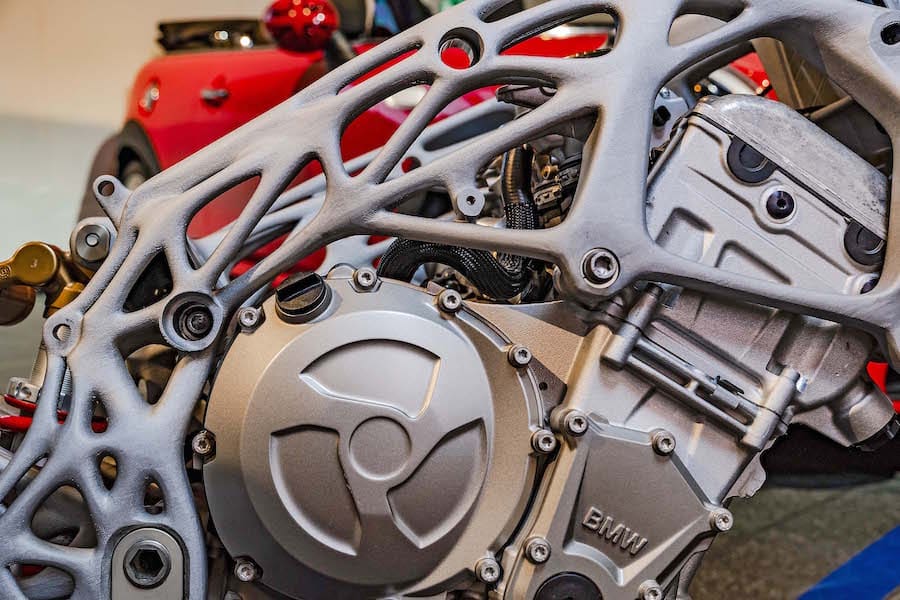

Its plan to fit 3D printers to its R1200GS range may have been an April Fool’s Day joke, but BMW isn’t kidding with its latest creation, a 3D-printed S1000RR frame and swingarm.

The firm unveiled the bike as part of its Group Digital Day, an event exploring the use of ‘digitalisation’ in personal mobility.

Rather than the term 3D printing, BMW calls the processes ‘additive manufacturing’.

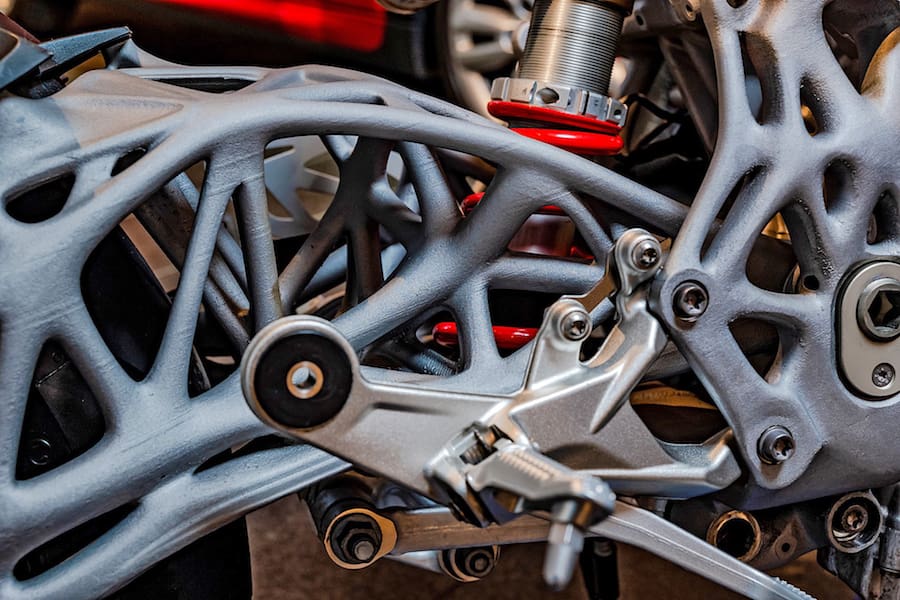

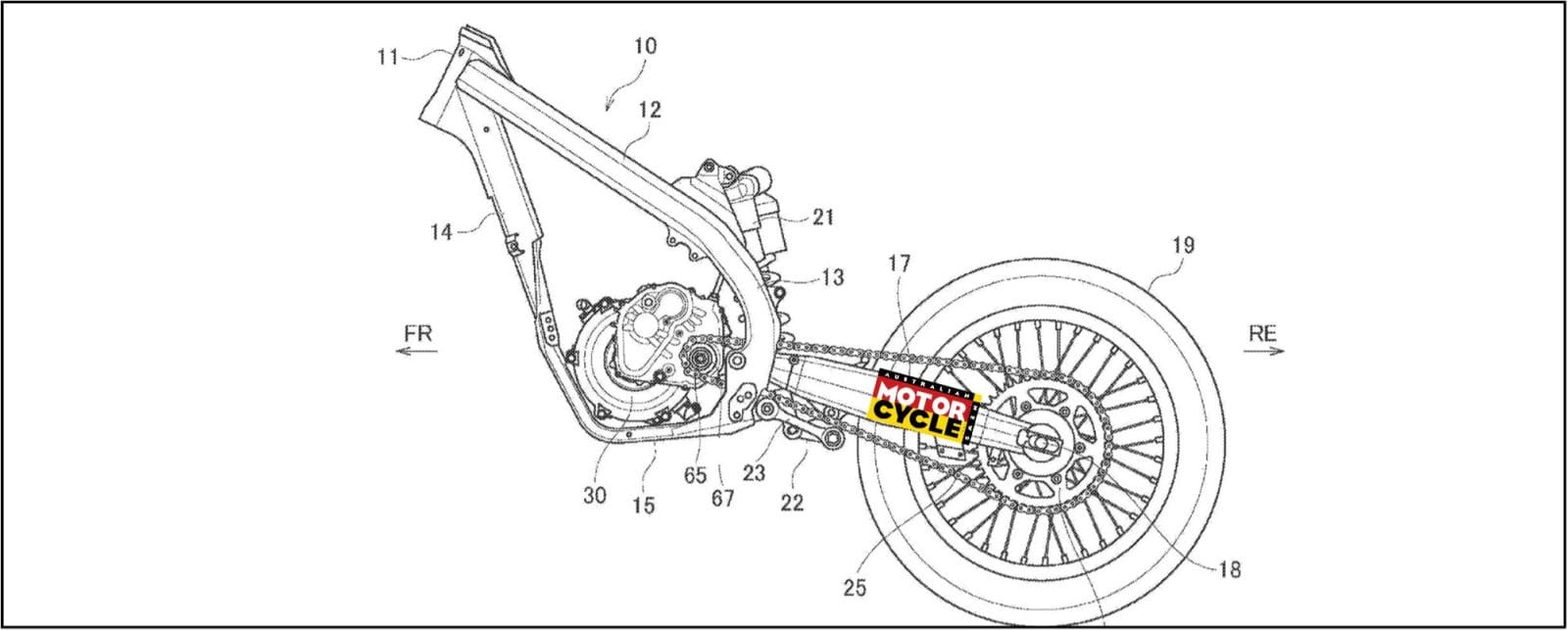

However, it means the same thing; building up structures from thin layers of molten material – metal or plastic – to create single-piece components. Often, these are shapes that couldn’t be cast, pressed, machined or moulded as a single part, and the S1000RR chassis illustrates precisely that.

Currently, 3D printing is particularly useful for prototyping parts that will later be mass-made using more traditional processes.

The system is fast and flexible, allowing one-off components to be made relatively quickly and cheaply, without labour-intensive machining or costly mould-making. In turn, that means it’s easier than ever before to tweak and change designs during the prototype stage, simply printing out a new part whenever an alteration is made.

Although a fully 3D-printed frame and swingarm isn’t likely to make sense for mass production, it’s easy to imagine one-off racers, like MotoGP bikes, using the tech. It would allow multiple variations of the same part to be made, with minor tweaks to the geometry or rigidity, without the hugely labour-intensive process of hand-making a new chassis.

It’s also quite possible that very small production runs of bikes – such as BMW’s carbon-framed HP4 Race – could in future be produced with a 3D-printed chassis.

By Ben Purvis