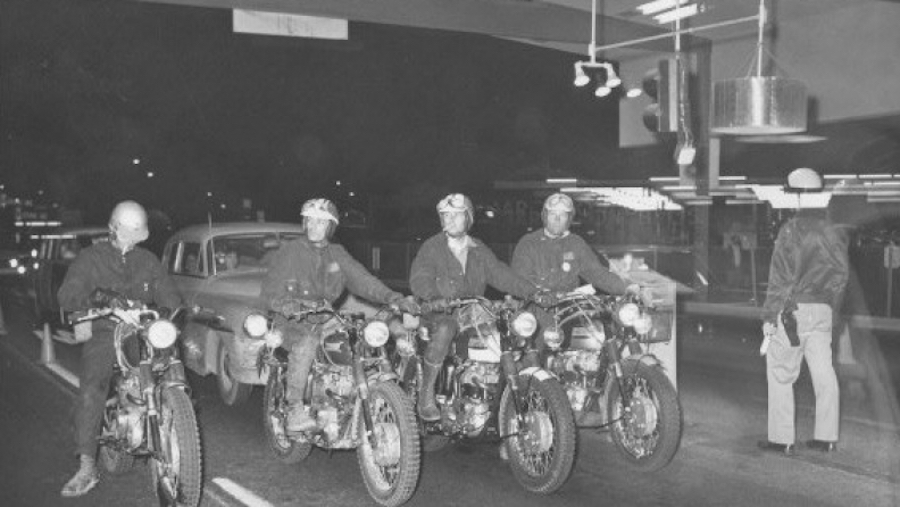

The granddaddy of all desert races is a perfect description of the Baja 1000. It’s the gruelling off-road race which just turned 50, half a century, reaching its golden jubilee. And to celebrate, the 2017 Baja 1000 retraced the wheel tracks of the first official running of the event back in 1967. Starting in Ensenada on Mexico’s north-west coast. On the stroke of midnight, 405 competitors launched their quest to conquer the Baja Desert and race 1134.4 miles (1825.6km) flat-out down the Baja California Peninsula to the finish line in La Paz. In order to be an official finisher, you (or you and your team) are required to complete the course within the imposed 48-hour time limit – one second over and you go down in history as a DNF. And although there is only one so-called ‘rider of record’ on the coveted finisher’s list, most teams comprise of somewhere between four and six riders, many of whom specialise in racing through the desert scrub at night.

The 50th Anniversary of this world-renowned event not only attracted the toughest off-road racers from 44 different American states, but a total of 27 countries were represented on the 2017 entry list.

The Baja is open to all comers, and the vast array of competitors, bikes and budgets is nothing short of a true spectacle and highlights the grit, courage and will to win that’s evident across all genres of motorcycle racing. Some riders are just there with a few mates in a bid to tick it off their bucket list, while the big-budget teams are there to win – and at any cost.

Most of the factory teams up the pointy end of the field will hire helicopters to ferry their riders and mechanics to check points, spare parts are flown from one spot to another rather than driven, and team photographers get dropped in the thick of the action for those all-important shots that the sponsors love. Baja is big business in the ’States.

Last year’s race favourites were American Honda’s A team, dubbed 1x, who lead out on their factory-prepared CRF450R, followed by the 45x Honda privateer squad. American Honda’s B team started third on their 3x machine, with the rest of the field left following in the three Hondas’ dust.

Leaving at midnight gives the night specialists six hours to prove their worth, and eke out a lead before the Mexican sunrise signals it’s time for the first rider change of the two-day event. By this stage, they are on the east side of the peninsula, south of San Felipe, and if the first rider thought the cover of darkness was harsh, the second rider is met with the race’s notoriously difficult sandy whoops section.

Unlike the sand whoops traversed in Australia’s annual Finke Desert Race, these are made up of coarse sand, hiding large round rocks, all waiting to deflect a wheel in any direction but where it’s pointing and, for the 250 continuous miles of relentless sand whoops, staying on course is paramount.

Absolutely everything has nasty thorns in this part of the world, and numb hands from barbs embedded under the skin are something every rider suffers during the race.

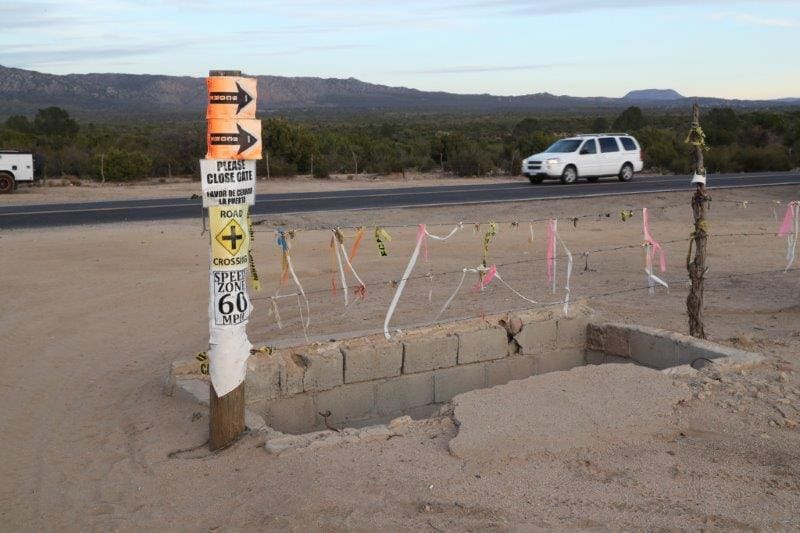

In a bid to complete the 1825km course, the teams need to set up around 21 pit stops along the way. There are some third-party companies (such as Baja Pits) who will fuel and service any bike whose rider purchases its services. It’s a necessary cost for the Ironman category riders such as Aussie Chris Warwick (see breakout) who lob into Mexico on their Pat Malone, chasing Baja glory as a solo rider, much like Dakar’s Malle Moto class.

Pit stops can be a hectic affair, especially when the 300x machine enters the wrong pit, realises, quickly changes direction, gets tangled in some bunting before cartwheeling as a result in the next set of whoops!

A broken collarbone put an end to that particular rider’s quest, but after losing two hours the bike was repaired and a back-up rider drafted in to continue the 300x squad’s plight. Surprisingly and amazingly, the team made up time during the next 10 hours, they regained the lead and went on to win their Over 30s class – that’s gutsy.

The race passes San Ignacio around the half-way mark, its palm trees and flowing river an enormously welcome oasis in the hot desert, and a stark contrast to the dry river beds and hard rocky ground surrounding it. It’s an opportunity to mentally prepare before hitting the course’s infamous silt beds further south.

These huge sections of track are like riding through three-feet deep cement powder, deep layers of super-fine dust which hides ruts, rocks, sticks and logs from the all-too-aware riders. It’s like Australian bulldust but finer, and the silt beds go on for miles. It chokes air filters, goggle foam and the riders’ lungs as they negotiate the energy-sapping sections.

Unlike previous years, the 2017 finish line was in the city of La Paz, a nod to the inaugural running of the event five decades earlier. At around 9pm, 21 hours after the first bike left the start line, the American Honda 1x team looked set for their second outright win.

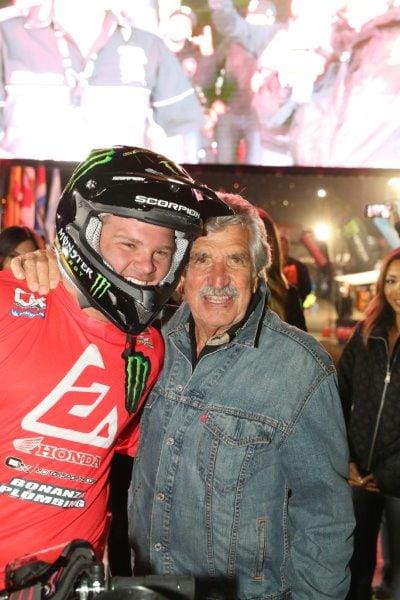

It was a tired and relieved Ian Young who wheelied the last few metres to victory, only to misjudge it and clip the podium ramp. He lost control of the bike, and it sent the assembled media and officials scampering for safety.

The team was slapped with a controversial and costly 30-minute penalty, which elevated the 45x privateer Honda of Francisco Arredondo to the top step of the 2017 Baja 1000 podium. One hour and 30 minutes later, the Honda B team crossed the line to take third outright on their 3x CRF450R.

The race ended how it started, with an all-Honda podium, which could suggest it came easy to the riders and their crews.

But if you think the Baja looks easy, ask the 42 percent of the field who were beaten by the relentless Baja Desert.