THERE is an aura about the Moto Guzzi 500 V8 that defies the fact that it raced for only two years (1956-57) and somehow never won a World Championship GP. Created exactly 60 years ago in a small workshop on the shores of Lake Como by a team of just 12 men, including the three engineers who conceived it, this bike is truly the stuff of legend.

With its improbable specification of eight cylinders, sixteen valves, eight carburettors and four camshafts, this remarkable 500cc motorcycle revved to 16,000 rpm safely, was measured at 286km/h along the Masta Straight at Spa-Francorchamps in its final race and produced 79bhp at 12,500rpm in its ultimate guise. Not even Honda’s 250/297 six or oval-piston NR500 can dethrone Moto Guzzi’s V8 from its throne as the Ultimate Racer.

The V8 came from the fertile mind of Guzzi chief engineer Giulio Cesare Carcano, who created its ultra-lightweight 250/350 singles that scooped eight world titles in nine years (1949-57), including five successive 350cc crowns. Having struggled for 500 success, Carcano briefly considered a V6 before opting for a V8. It had the potential to be no wider than the Gilera in-line four then dominating 500GP racing, with the advantage that it could rev much higher while a 90-degree cylinder angle would give the desired primary balance.

Amazingly, the whole bike was conceived, designed and assembled in the space of just five months. The first prototype ran on the dyno on April 10, 1955 – from the outset it delivered a promising 62bhp at 11,500 rpm – and four days later Australian works rider Ken Kavanagh rode it up and down the road outside the Guzzi factory, to the excitement of the assembled crowd. “It sings so beautifully, we should take it to La Scala!” an evidently impressed Guzzi executive is reported to have exclaimed.

When the test team assembled at Monza, Guzzi’s reigning 350cc world champion Fergus Anderson, who had been appointed team manager, turned up unexpectedly and demanded to ride it first, rather than the waiting Kavanagh who was to race it the following month. The 46-year-old Anderson then proceeded to crash on his very first lap, destroying the engine. This expensive mistake set the project back some weeks, delaying its public debut until practice for the Belgian GP at Spa. However, a broken small-end bearing and difficulty selecting fifth gear prevented Kavanagh from racing the V8. In fact, mechanical problems kept it from racing at all that year.

After major mechanical changes ahead of the 1956 season – replacing the 180-degree flatplane crank with a 90-degree crossplane crank, and the six-speed gearbox with a four-speeder – the V8 finally made its race debut in the Imola Coppa d’Oro on April 25, where in pouring rain Kavanagh sensationally took the lead on lap 3. The Aussie pulled away from the champion Gilera fours, as well as his teammates Bill Lomas and eventual winner Dicky Dale on Guzzi 500 singles that were theoretically better suited to the conditions. But after leading for 10 laps Kavanagh pitted for fresh goggles, then rejoined to set the fastest lap before retiring with mechanical trouble.

The revised bike continued to show promise, and prove troublesome. Kavanagh also found the V8’s wayward handling around Spa’s ultra-fast curves too frightening to continue riding it, and pulled into the pits to retire, which displeased Carcano and resulted in the Aussie eventually leaving Moto Guzzi.

Lomas took over the V8, which gained modified steering geometry aimed at curing the high-speed instability. In the German GP at Solitude in July, in front of a massive 160,000 crowd, the Brit had a titanic battle with Gilera’s reigning triple world champion Geoff Duke, which ended when both were forced to retire, the Guzzi with a split water hose after setting a new lap record.

“This was the first time I realised we might have trouble on our hands with the Guzzi V8,” Duke told me many years later. “It was obviously very fast, and Bill Lomas was just the right chap for them to give it to. I felt quite apprehensive about its potential, once they’d sorted out the usual growing-up problems of a completely new design, especially one as complicated as this.”

Another Aussie, Keith Campbell, joined the Guzzi team but the V8 continued to suffer mechanical problems – though this didn’t prevent Dicky Dale setting a series of speed records at what is now Brescia Airport with his first ride on the V8.

For 1957, while still trying to resolve the issue of vibration caused by crankshaft flex, Carcano developed a 350cc version of the V8, employing the same major castings but with a 39mm bore and 36.6mm stroke. The engine delivered 54bhp on the testbed – more than the heavier GP-winning MV Agusta 350 four then delivering 48bhp – but in testing at Monza it was unable to come within nine seconds of the single and the project was terminated.

Instead, after extensive winter testing, the revised 500cc V8 notched another set of FIM world records before finally scoring a win, by Giuseppe Colnago in the first round of the 1957 Italian championship in March. Five weeks later, Dale made it back-to-back victories with a dominant win in the Coppa d’Oro at Imola. This was unquestionably the V8’s finest hour as Dale scythed through the field after a slow start to defeat the hordes of Gilera and MV fours. Lomas was absent after crashing in the earlier 350 race and breaking his collarbone, but would return at Assen, only to crash the 350 again, this time sadly ending his career.

Campbell put his V8 on pole for the non-championship race on the ultra-fast Mettet street circuit in Belgium, only to retire from the race complaining that the dustbin-faired bike was unmanageable in the windy conditions. For the Isle of Man in June, Dale ran so-called ‘partial streamlining’ – a dolphin fairing developed in readiness for the banning of dustbin fairings in 1958 – and finished fourth in the Senior TT.

Dale’s season ended later that month when he crashed in the Dutch TT at Assen, but Aussie teammate Campbell climbed through the field to second behind eventual winner John Surtees’ MV Agusta after getting away slowly – he still had problems firing up the V8 engine at a push-start – before retiring with clutch problems. There had been no fewer than four V8 Moto Guzzis in the Assen pits, but nobody to ride three of them…

A week later, on July 7 at Spa, Campbell was again the lone V8 Guzzi rider, and he surged into the lead ahead of Surtees, but after smashing the lap record and seemingly headed for certain victory, the Aussie was stopped by a broken battery lead.

Nobody knew at the time, but this turned out to be the Moto Guzzi V8’s last race. For the next two GPs Campbell (who would soon clinch the 350 title) and rode a 500 single better suited to the twisty circuits, and in pre-race testing before the Italian GP at Monza the Aussie crashed and broke his pelvis. With all its riders sidelined, Moto Guzzi arranged for Surtees to secretly test the V8 with a view to joining the team for 1958. But the test never happened. Instead, the road racing world was dumbfounded by the announcement that, in conjunction with fellow 1957 world champions Mondial (125 & 250) and Gilera (500), Moto Guzzi (350) was withdrawing from racing.

The most exotic Grand Prix motorcycle ever made would never race again.

Simply the best

Bill Lomas, who died in 2007, was the rider perhaps most closely associated with the Guzzi V8. After being reunited with the machine in 1981, he described it as “the greatest machine ever made!”

“It was years ahead of its time, and it was so bloody fast – faster than anything else around back then! But it needed to be set up carefully for each rider.

“People used to say it didn’t handle very well, but that’s not true, as I proved when I had that battle with Geoff [Duke] at Solitude. You needed to pay a lot of attention to setting up the leading link forks for the rider’s weight, and how you sat on the bike, but the engine was just out of this world – there was no power curve as such, it just went all the way from low down in a straight line to 16,000 revs if you wanted to, though we kept it down to 12,500 just to be on the safe side.

“If Moto Guzzi had kept going after 1957, things would have been very different, I promise you. In the 1960s Honda would have had to build something better than their four, and the MV triple would have struggled against the V8, no question.

“Carcano was a genius, and the V8 was just the ultimate example of his intelligence. It was a real lost opportunity.”

ENGINE ARCHITECTURE

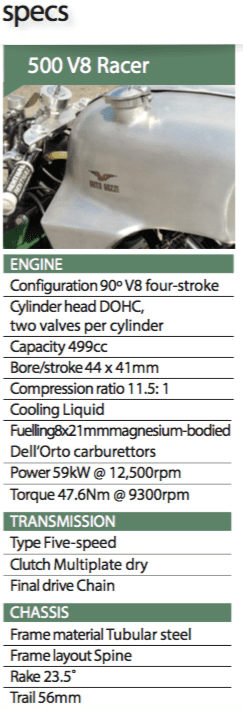

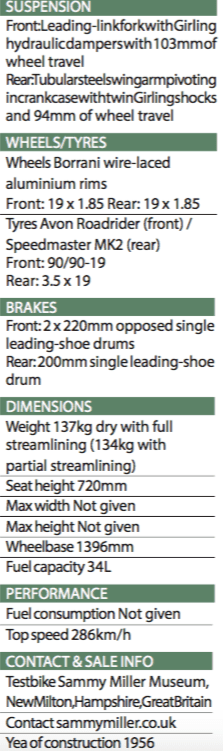

The dry-sump V8 measured 44 x 41mm for a capacity of 499cc (interestingly, Honda adopted the same dimensions for its 250 four a decade later). The two banks of cylinders were set at 90 degrees on a one-piece cast magnesium crankcase, which incorporated the unit-construction gearbox with gear primary drive. Ahead of its time, the crankcase casting also featured a ribbed 40mm diameter bronze-bushed pivot to house the rear swingarm to increase stiffness and save weight. The engine weighed just 56kg and, measuring a mere 460mm across, allowed the complete bike fitted with full streamlining to be only 30mm wider than Guzzi’s 350 single. Total bike weight was an amazing 137kg dry with full streamlining (134kg with partial streamlining), just 5kg heavier than a similarly faired Manx Norton single.

CRANK DEVELOPMENT

The original forged one-piece five-bearing 180-degree flat-plane crankshaft with full-circle flywheels necessitated bolted-up steel conrods with split roller bearing cages. It was chosen by Carcano to deliver a lower, more compact crankcase format. The outer main bearings were mounted in the crankcase covers, with a ball bearing on the drive side and a timing side roller. Owing to concerns about crankshaft stiffness, and the high-frequency secondary vibration endemic in a flat-plane crank, this was replaced by a 90-degree crossplane crank, originally a one-piece component similarly made by Hoeckle in Germany. However, this didn’t cure the vibration, so for 1957 another crossplane crank was sourced from Germany, this time a nine-piece built-up one from Albert Hirth. The Hirth crank had pairs of one-piece steel conrods sharing common crankpins. It resolved the problems of flex and vibration. Like today’s world champion Yamaha YZR-M1, the Guzzi V8’s crank ran backwards, though whether Carcano chose this for the handling benefits that reputedly follow is unclear.

CYLINDER HEADS

In spite of Moto Guzzi’s pioneering work with four-valve cylinder heads as far back as 1924 on its 500cc singles, Carcano chose a more conventional two-valve set-up to avoid further complicating what was already an intricate design. The 23mm inlet/21mm exhaust valves were set at a very modern 58-degree total included angle, running in bronze guides but with no inserts for the valve seats owing to machining difficulties back then, which meant the cylinder head became scrap as they inevitably wore. Each valve used dual Alba coil springs and was operated directly by the cams via bucket tappets, eventually with 6.5mm of lift for the 1957 season (previously 6mm), an apparently minor change Carcano said gave considerable extra power, when combined with new, more aggressive cam profiles. The four overhead camshafts were driven by a train of six straight-cut gears enclosed in a timing case on the right side of the engine.

GEARBOX

Carcano’s original design employed a six-speed gearbox because it was feared that such a high-revving engine would have a narrow power band that would dictate more ratios to keep it buzzing hard. But early tests proved the opposite, with a broad range of usable power from 7000 to 11,000rpm, so to save weight and friction Moto Guzzi went to a four-speed for 1956. This proved a step too far except on tight, twisty tracks, so an eventual compromise saw the V8 running with a five speeds for 1957, in each case matched to a dry clutch with just seven plates – three metal and four friction, and the gear primary drive common to all Moto Guzzi GP racers employing straight-cut teeth and offering a 2.76:1 reduction.

CHASSIS

This exquisite V8 engine was fitted in Moto Guzzi’s trademark spine frame, first introduced on the 120º V-twin Bicilindrica 500 in 1948, and subsequently adopted on all its 250/350cc world title-winning singles. This comprised a 85mm-diameter central tubular backbone made from chrome-moly steel, with a twin-downtube duplex steel cradle frame supporting the engine, a well-triangulated rear subframe, and the swingarm pivoting in the crankcase, controlled by twin Girling shocks giving 94mm of wheel movement. Guzzi’s proven leading-link fork was used, offering 103mm of wheel travel, with long hydraulic Girling dampers in front of each leg and a pair of opposed 220mm single leading-shoe drum front brakes. A 200mm rear SLS drum was fitted. The 19-inch front wire wheel had a 2.25in-wide Borrani alloy rim, the rear containing a rubber cush drive was a 3.00 x 20-incher. A massive 34-litre fuel tank allowed the thirsty bike to finish the long GP races of the day.

Must visit

The Sammy Miller Museum in New Milton, Hampshire, UK, is crammed full of interesting machines – including one of the biggest collections of exotic racing bikes in the world, and all are runners! These include the V8 Moto Guzzi, AJS Porcupine, Mondial 250 with dustbin fairing, Nortons, Ducatis, Suzukis, Hondas, Velocettes and many more. The Road Bike Hall includes a huge collection of factory prototypes and designs from all over the world, and of course there are plenty of dirtbikes and trial icons, too – over 400 bikes in total.

The Museum is open to visitors from 10am every day.

Contact: Sammy Miller Museum, Bashley, New Milton, Hampshire B25 5SZ, UK.

For further information and details visit www.sammymiller.co.uk.

Dreams Come True

IT WOULD be the dream of anyone fascinated by the history of Grand Prix racing to ride the Moto Guzzi V8, and I fulfilled that dream thanks to the generosity of famed British collector Sammy Miller. After a shakedown test at the local WW2 airfield that doubles as the Miller Museum test track, I was given the honour of riding the bike up the hill at Goodwood – twice.

Riding the V8 Guzzi is very much an acquired skill – whether with the original full dustbin streamlining fitted (as I did in 2014), or with the bike naked as nature intended, which Sammy did in 2012 so the hordes of enthusiasts who clustered around all weekend could appreciate the mechanical jewelry. It takes three men 20 minutes to remove the dustbin streamlining, with the constant risk of scraping the paint against the ground at a busy place like the Goodwood paddock.

I was very aware of the bike’s value, and the time put in by John Ring, the Miller Museum’s mechanical magician responsible for recommissioning the engine after its two decades-plus hibernation in an Italian lockup, but I ended up riding it as close as I dared to something approaching its true potential, observing the 12,000rpm limit stipulated – just 500 revs down on what was used in races.

Another challenge is the extremely individual riding position, with the twin batteries mounted either side of a plush suede leather seat that forces your legs apart. It’s a bit like riding a horse. Then there’s a long reach forward to flat-set handlebars over a long, unpainted, bare alloy fuel tank. It has poor steering lock for tight turns, where the bike feels rather ungainly even without the bodywork fitted – and a great deal more so with the dustbin fairing in place.

Moto Guzzi’s own wind tunnel at its Mandello factory must have played a part in developing this rangy riding stance, which allows you to rest your rib cage on the back of the tank as you tuck right down behind the screen, with the all-enveloping dustbin fairing giving you the impression of wafting along on a magic carpet of metal and perspex. It’s an eerie, uncanny sensation, and on the Guzzi V8 this feeling of detachment and remoteness is amplified by the surprisingly quiet exhaust and smooth, vibrationless engine. It just whispers along the tarmac.

The controls are in keeping with the period, with a hefty friction steering damper sticking up out of the fork yokes, but slender, gracefully curved clutch and brake levers that are surprisingly light considering how massive the dry clutch is to harness what was then a monstrous amount of power. The traditional white-faced Veglia rev-counter reads to an astronomic 15,000rpm, with a redline painted at the safe 12,500rpm redline its riders were asked to observe, flanked on the left by a small Acqua temp gauge with a dab of green paint at 60 degrees and a red one at 90.

It takes a very long time to warm the V8 engine up from cold to the required 70 degrees. Before firing it up, fuel is squirted down each of the eight carbs’ long intake trumpets, then you flick the ignition, select bottom gear on the one-down four-up right-foot gearshift, and you only need a few paces’ shove to clutch the V8 effortlessly into life with a silky purr from the straight exhausts. You need to warm it up at a constant 7000rpm, with occasional blips to keep the plugs from fouling, but it takes 20 minutes for all that metal to heat up.

It pulls cleanly off the line, where it’s best to take a big handful of revs that would send the valves floating on a twin or single, then feed the clutch out slowly. It’s not a heavy bike, but it takes a while for the motor to build up momentum from rest, or out of a slower turn, presumably thanks to the inertia of its quite hefty full-circle flywheels. But when that Veglia tacho needle hits 7000rpm, the V8 Guzzi picks up its skirts and flies, accelerating strongly as you feed in each successive evenly spaced gear. Change action is ponderous, so you must be quite deliberate, and always use the clutch. Thanks to the effortless way the V8 builds speed, and its forgiving, flexible nature, this is a bike that for all its bulk and the idiosyncratic riding stance is really quite relaxing to ride hard once you get in the groove.

It’s by no means quick steering, but it hustles through turns pretty well, thanks to a short 1396mm wheelbase and the tight 23.5-degree rake for the leading link forks, with their amazingly reduced 56mm trail. There’s quite a pronounced 45:55 rearwards weight bias with a 75kg rider and, while I didn’t get any trace of weave round faster turns, that might have been because we were running it mostly without a fairing. Ken Kavanagh especially was convinced that the dustbin streamlining was actually generating lift at the front, which lightened the front wheel and started a weave that was often hard to control without backing off the throttle; for me it handled just fine – but the driveway to Goodwood House is not the Monza autodromo or the Isle of Man TT course…

Perhaps it’s fortuitous that the single rear drum brake on the Miller bike works better than the double-sided front, or perhaps it was deliberately set up that way to lessen the risk of locking the front wheel under heavy braking from high speed.

The twin Girling rear dampers deliver a suspension action that’s compliant by the standards of the era, and not nearly as stiff as I expected, sitting down well over bumps though skipping a little over the worst ridges in the old airfield’s concrete joints. The leading link fork worked okay, but I can’t say I gave it a serious exam; the ride quality was quite good over those bumps and ridges, but it takes a while to get used to the bike staying so flat when you squeeze the front brake, the minimal front-end dive resulting in a slightly dead feeling to the brake.

After finally achieving a life’s ambition, riding what by any standards must be road racing’s ultimate racer, I can only say it fully lived up to my expectations. As Bill Lomas said to me 30 years ago, what a shame Moto Guzzi pulled out of racing when it did, otherwise the 500GP class in the 1960s might have been even more thrilling technically, with another Italian contender for top honours against Honda and MV.

And I can’t help wondering – and regretting – that a company which produced such a mechanical marvel should have ended up as Italy’s answer to Harley-Davidson, today producing only pushrod V-twin custom bikes.

Alan Cathceart

Photo credit: Kyoichi Nakamura