If you’ve been reading AMCN for a while, you might have seen and read the odd bit about my Martek a few times in the nearly six years since I bought it. I first noticed this bike when it was in a mate’s motorbike shop. I said, there and then, if it ever came up for sale I’d have it. Years later, it eventually did.

Martek were a UK company who built streetfighter chassis’ back in the ’90s. They eventually went out of business, because, I think, they were better welders than businessmen. This isn’t one of their frames but a 1991 GSX-R750W they modified, and the quality of the work on it is something else. It’s the welding and machining and some of the ideas that made me fall in love with the bike. One of the bosses, Mark Walker, built it himself using some of the best superbike parts at the time, like Marchesini wheels from Haga’s R7 and Superbike-spec Öhlins forks and AP six-piston brakes. Proper rare stuff.

I hadn’t had the Martek long before I started dicking about with it. I rode it at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, then took it to bits and that’s how it stayed for years. The engine would probably still be under my workbench if it hadn’t been for the TV lot. After the success of the first series of Speed, the production company that makes the programmes, North One Television, were badgering me to make another. I loved doing the first series, but I didn’t want to keep doing the same things, so me and my mate Andy Spellman came up with a few ideas. One was to race the Martek at the Pikes Peak International Hillclimb in Colorado. The TV bods liked the idea and that was it, the pressure was on.

The bike was still in a thousand bits, and very little of the work that I planned to do when I stripped it had been carried out. In fact, it had gone backwards. A mate promised he’d weld me a new subframe, but he didn’t, so I bought my own TIG welder. While getting the bike off him, after weeks of it gathering dust, it fell over in the back of my van and put a big gouge in the petrol tank. Bastard.

I had found a few rare parts, though, like the MTC big-bore cylinder block, plus a dry clutch and magnesium casing from the race kit from the time.

Those with long memories might remember me talking about wanting to get 500bhp out of this motor. At the time it appealed, because it was a nice round number, but I realised it would make the bike unrideable in a race like Pikes Peak. These motors can make that power, but I’d have to fit a lock-up clutch and that would make shifting hard. In the end I didn’t set a figure, I just built the motor I was happy to build.

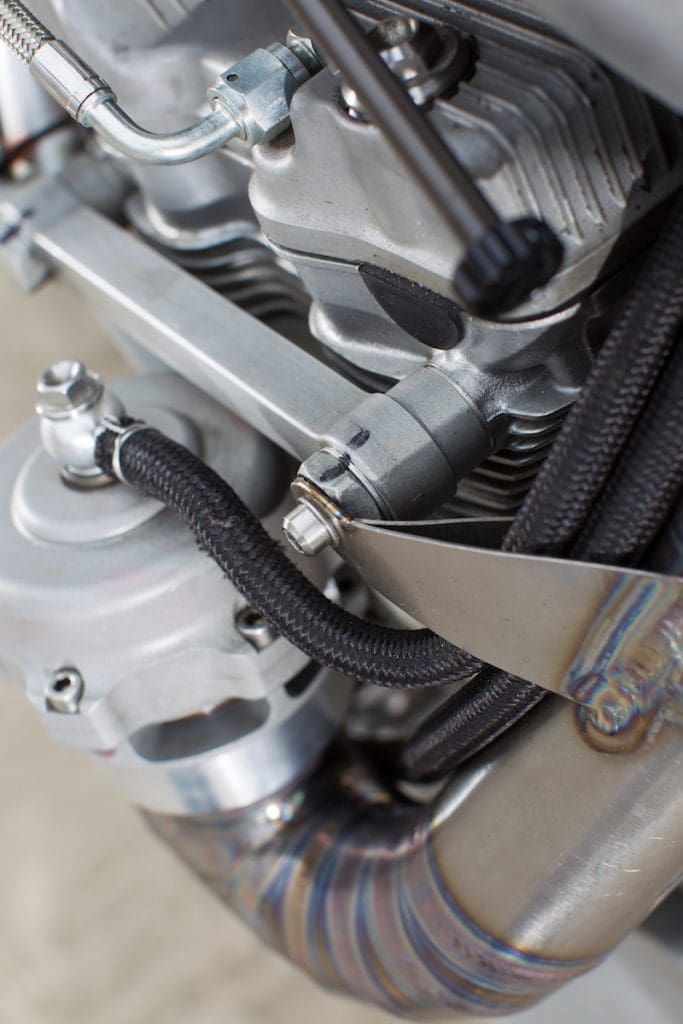

I started with the 1986 GSX-R1100 cases. I wanted to go big, so I hunted down the MTC big-bore barrel. It turned out Mark Walker, the original builder, had one sat on his shelf. Once I had that, I needed to machine out the crankcase mouths to take the MTC block, because the skirt is a bigger diameter than the original. I fitted the block with specific turbo liners from MTC, with a top hat section to stop it moving in such a big-power engine.

The bores are so big in the block there’s no room for the oil feed channels to the top end, so there’s an external oil feed. You can see the link pipes on the side of the cylinder.

The head is from a 1989 GSX-R1100 because the valves are bigger. I put the head in my oven at 180˚C for an hour so I could knock the valve guides back into the head and get the port as big and nicely shaped around it, before knocking the valve guide back through. Normally, I’d just cut the valve guide back while I was porting, but I reckon the valves need support in this engine. The porting itself wasn’t done with the same finesse I’d use with a normally-aspirated motor. There’s so much more pressure pushing the mixture into the combustion chamber that you don’t need to be as precise.

The boost from a big turbo can open the inlet valve, so I fitted MTC heavy-duty valve springs. The crank is standard, but the rods are from Carrillo; the cams are Kent SUZ212s and the low-compression, turbo pistons are from CP. The compression is just 7.2:1.

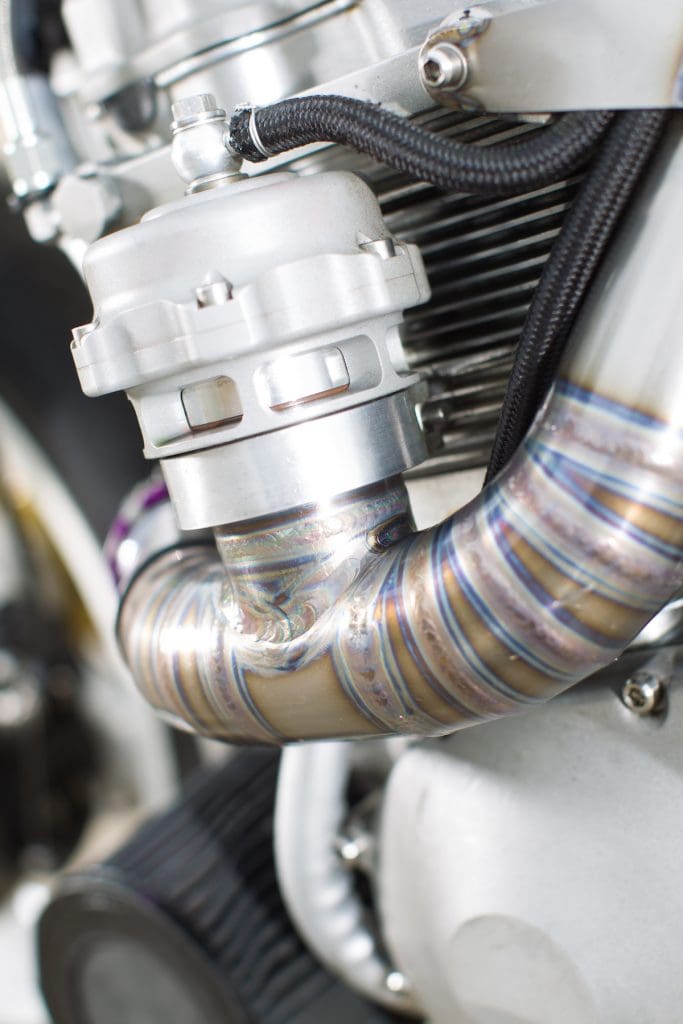

The turbo has all new plumbing with the headers and exhaust being made by UK exhaust specialists Racefit. The turbo is a Borg-Warner S200, a decent size and a good stand-alone turbo, the kind people fit to Mitsubishi Lancer Evos. The turbo is mounted a bit too low, but it has to be where it is to clear the front wheel. Because it’s mounted low I need an oil vacuum pump to help draw oil through the turbo to keep it flowing. I needed a 0.4mm hole where the oil feed goes into the engine casing, to restrict the flow of oil, and I didn’t have a 0.4 drill, so I used the main jet out of a Suffolk Punch engine. It’s good to have a bit of lawnmower in there somewhere.

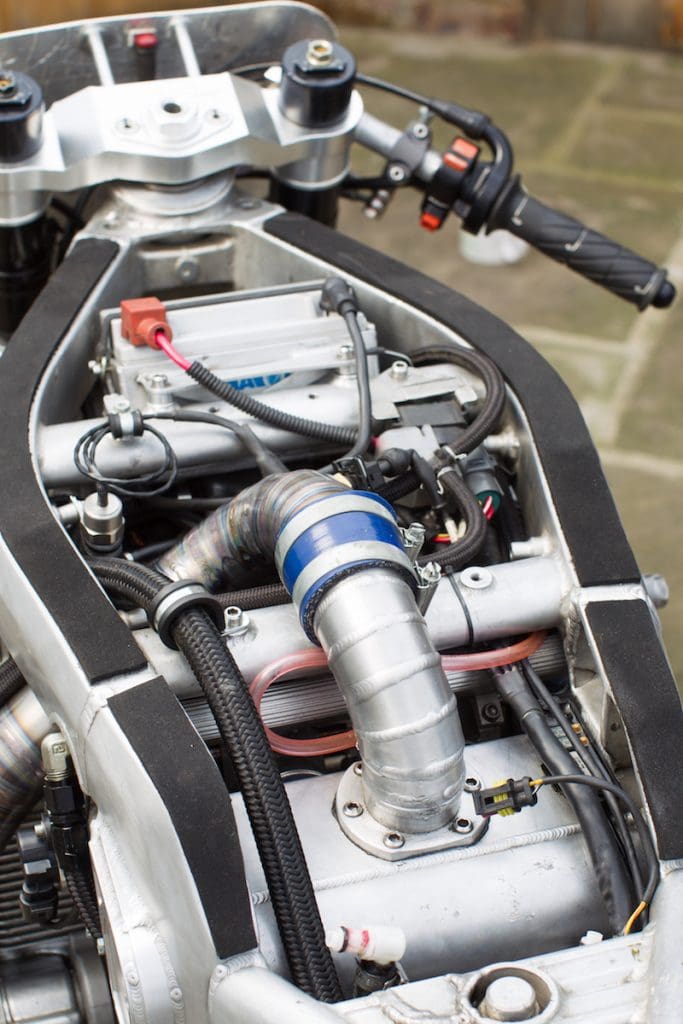

I didn’t want any logos on the engine, so I machined all the numbers and lettering off the turbo and cases. I wanted the turbo installation to look as neat as possible, so I had Racefit weld a longer outlet to the turbo, to make a curve to meet up with the charge pipe (that leads to the plenum). It connects to lobster-backed titanium charge pipe with a purple Wiggins clip. On top of that pipe is the Tial 80mm dump valve. It’s there to equalise the pressure on a closed throttle and stop the turbo stalling. The K&N air filter fitted to the turbo is massive, but it’s flexible and just moves when it touches the road through corners.

The plenum chamber, a turbo’s airbox, is welded into the Suzuki frame. I bought the 42mm throttle bodies from America, but they weren’t brilliant quality and I had to tidy them up. The injectors weren’t big enough either, so I had to machine the throttle bodies to take Bosch 400ml injectors. Bigger injectors would flow more fuel but they wouldn’t give good response at low speeds. I also fitted the throttle bodies upside-down so there’s fresh air beneath them and you can see right through the bike. That’s just for looks not performance.

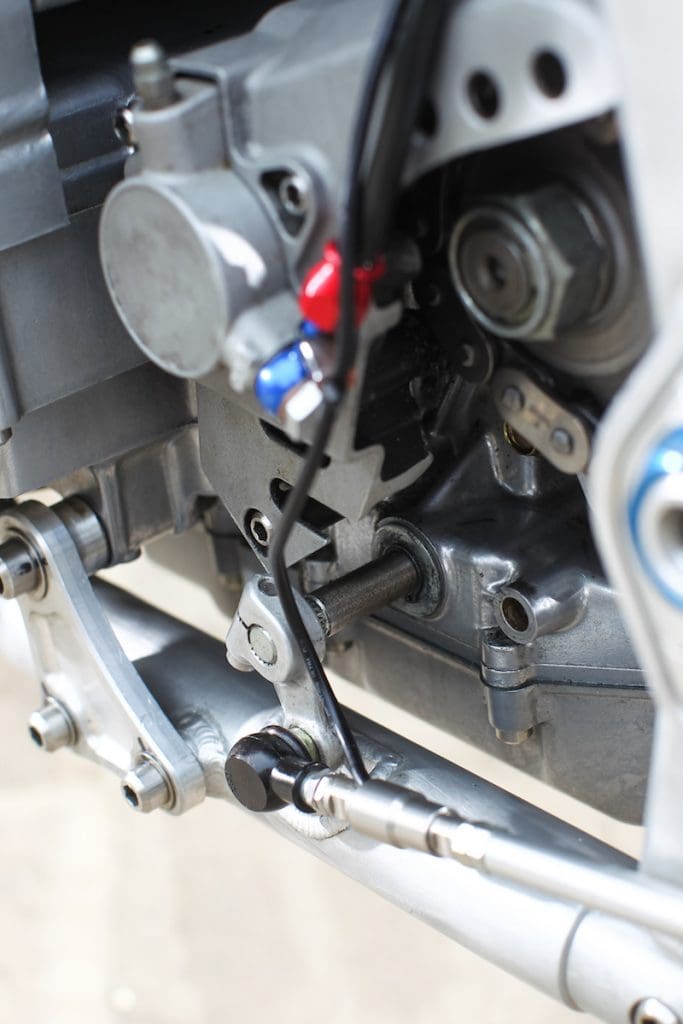

The dry clutch is part of the race kit from 1991. My original plan was to make one, but I didn’t have time, so I got this one from Goose at York Suzuki. He’s the man for finding rare parts like this. In 1991, so I’m told, the price to race teams for this dry clutch was £24,000. They normally came with a cover, but after all the grief it took to get a dry clutch I’m not covering it up.

GSX-R750RR homologation road bikes had dry clutches too, but they’re different to this. The race one has two oil sight glasses, one for when the engine’s cold and one for when it’s hot so it can be checked during an endurance race.

Another of the rare-as-rocking-horse-shit parts I’ve fitted is the Yoshimura six-speed close-ratio gearbox. There can’t be many six-speed, dry clutch GSX-R1100s in the world. If there is another, I bet it’s not turbocharged.

I spoke to a few turbo experts, Jack of Holeshot and Sean from Big CC about helping me build the bike and though they really know their stuff and wanted the bike to help me finish it, but I was beginning to feel like the job was being taken out of my hands. I didn’t want to just hand it over to someone and pay the money, so I kept plugging away. I couldn’t make the loom myself and I wanted it to be as neat as possible, so I went to Track Electronics. I’d come across one of their looms in a hillclimb car and it was a work of art, so noted the name for future reference.

I could’ve gone down the MoTeC route, but that would mean I had to run a separate boost controller and I didn’t want that, I wanted it all in one box, so John at Track Electronics had a custom ECU made by Specialist Components, also in Norfolk, UK.

John got the bike running in a week and we found a couple of oil leaks, that I sorted and found out the turbo needed the oil return feed. Then it went back to Norwich for the electronics to be finished. I got it back, fit different forks and shock, swapping Ohlins for K-Tech, then went testing at Cadwell. That was the first time I rode the Martek in years. Two days later it was in a container on its way to Pikes Peak.

After Pikes Peak I said the Martek would sit under my stairs and never turn a wheel again. It won its class at Pikes Peak, but then I rode at Cadwell and it never run right. Then I took it Glemseck in Germany, a big café racer festival that I go to with the fellas from Red Torpedo, and the clutch was slipping but it was running well, and I realised it’s too good to stick under the stairs, so it’ll have more outings when the mood takes me.

WHAT’S IT LIKE TO RIDE: GUY’S VIEW

It’s just so nimble. The weight’s in exactly the right place, but that’s more by luck than judgement. Most of the dimensions of the bike are the same as Honda 954 Fireblade. The ratio of the rear shock, swinging arm position, the steering head angle and position are all the same, but the weight distribution, with this heavy, old engine, is much further forward than a 954.

I moved the engine back in the frame, but it’s still a very big, long and heavy engine. I can carry a new complete GSX-R1000 engine around the workshop, not no problem, but I can do it. There’s no way with the GSX-R1100, it’s a two-man job. Bloody massive thing it is.

Everything says the bike should be a nightmare round Cadwell Park circuit, but it’s dead nimble and stable. The only problem is getting it stopped, just because of the weight of the thing. At Pikes Peak it was no bother, because I had the assistance of the hill’s gradient helping me into the corner.

What makes it so good is the initial power. From nothing to the first feeling of the boost is impressive. The turbo’s not working at its optimum until 5-6000. The initial part of boost, from 5-7000prm, is dead progressive, really nice. It’s beyond Superbike fast, but it’s not mental. When you get further up the revs, where it’s making two-bar boost, it’s getting to be too much. The thing goes from making mega power to ridiculous power.

I had the bike dyno’d in Colorado and it made over 270bhp at a mile and a half above sea level, so it’s got to be 300bhp at sea level.

WHAT IT IS LIKE TO RIDE. GARY’S VIEW

‘Do you want to ride it then?’ says Guy. Well, I think, yes and no. ‘It’ is a 300 or so horsepower turbo bike. It’s not insured. Or road legal. Or registered. It does have a number plate, but it’s the size of a hot dog bun. There isn’t even the thrum of a hedge trimmer to puncture the calm of this Saturday morning, at the cusp of autumn, in the sleepy North Lincolnshire village he calls home. But I’ve visited Guy’s house dozens of times and I don’t remember seeing a copper around here, so… OK!

The battery’s a bit lazy, so Guy brings his Snap-On booster out of his Transit van to give it a hand. It starts straight away. The bike has no baffle, but turbo bikes aren’t as noisy as a regular GSX-R1100 with an open pipe would be. Still, I’m not going to be sneaking around the countryside. Time to go.

Immediately I notice the ergonomics are set up how Guy likes his race bikes, arse high, seat quite steeply angled, forcing weight over the front. The pegs aren’t 125 GP high, but still higher and further back than stock. The clip-ons are below the top yoke.

Steering is heavy, due to all the weight over the front, but the engine pulls from nothing, smoothly. The bike is remarkably well behaved. It ticks over, loudly, it has some steering lock, it pulls cleanly low down, but it takes time to clear its throat when the turbo should be kicking in, making me even more apprehensive. I’m only riding in the realm of ‘Superbike fast, but not mental’. Still, I’m on cold tyres on dirty country roads. As road tests go, this makes as much sense as a Greek accounts ledger.

It sounds vicious and revs like a Formula one car, so sharp. ‘It must be the size of the throttle bodies, because the turbo has nothing to do with it,’ says Guy.

I find something of a straight, blast past a car like a pod racer and things start happening. The very potential of the bike is intimidating the life out of me. I admit it. I can’t gauge how fast I’m going, because the thrust feels different, more like a tsunami. It might be linear, as Guy suggests, but the line is steep. I’m not really taking much in. Would I like to be tasked with racing up to the top of a 14,000ft American mountain? I would not. I’m bloody happy to give it back in one piece.

PIKES PEAK v THE ISLE OF MAN

It hard to compare Pikes Peak and the TT because they’re so different. As an event, Pikes Peak is like nothing else. One thing that sticks in my mind is how much later you brake, even on a 220kg turbo bike. The hill helps the brakes, because it’s so steep.

Pikes Peak is more of a pure motorbike event [though the bikes are just part of a large field that ranges from electric cars to races trucks]. Proper bikes and proper blokes. I loved that. It brought it back home that’s what I love about racing, the motorbikes, not the bullshit.

There are cliff edges and there’s a lot that could gone wrong [one competitor died after crossing the line, misjudging the braking area and running off the side of the road, shortly after Guy’s run this year].

I knew the track before I’d even seen it, because I put the effort in. You get out what you put in and I knew it when I got there. I was on the pace, more or less straightaway.

Some riders get confused in a section of hairpins called the Ws. It’s first, second, third, back to first; first, second, third, back to first for a bunch of hairpins, then, Right at the end of the Ws is a blind left-hander, not a hairpin. I knew when I come to the snow I could go flat out. That sections very much like the 32nd, 33rd and Windy Corner section before Kate’s Cottage at the Isle of Man.

Pikes Peak is mega but it doesn’t give me the outright buzz of the TT, because you haven’t got the speed, you’ve got the cliffs, but not the pure speed.

I fancy going back with something even more strange. I’ve no interest in racing there with a modern superbike. I felt like I was playing the part with my Martek. People are rocking up in vans, old bikes cobbled in sheds and I felt like I was one of them. I’m building a supercharged Rob North Triumph T160 triple. That would be good there.

WHAT WENT WRONG AT PIKES PEAK?

If you’ve seen the episode of Speed that features Pikes Peak, you’ll know the Martek didn’t run right there. I could ride it to 5000rpm, then it would lose power and everything on the computer would freeze and cut out. When the revs dropped to 1500rpm it would start making power again.

We changed the fuel, the map, everything we could think of. We went to a local dyno and it made 273bhp at 6000ft above sea level, but we were still effing about at 3am before 5am practice. I raced it like that, not revving above 5000rpm, the bike hardly coming on boost.

After returning to the UK I rode it at Cadwell Park, and it died completely. This time, because it had died and not come back to life at 1500rpm, I could finally see the problem – the fuel pressure was forcing the valve shut in the fuel line break. I don’t know why it was making every sensor freeze, but I think I’ve sorted it now.

By Guy Martin/ Gary Inman

Photography: Paul Bryant