The Fireblade is back and yes, it is better than ever. It’s 90 per cent new, lighter, smaller, with more power and a plethora of rider aids. In SP form it looks stunning too – and so it should for $28,499 (+ ORC).

It clearly says Honda on the side, and it’s definitely a Fireblade; but it wasn’t what I was expecting. Over the years, just like me, the Blade has got a little soft, put on a bit of weight, and appeared bulky alongside sharper and younger models. But it’s a different story with the new bike. It’s still a Blade, albeit a much smaller, lighter and thinner one. While the position of the ’bars, seat and ’pegs doesn’t feel much different to the old model, the screen is tiny and the frontal area is small, almost like a 600cc supersport. Down the straight at Portimão, with the full colour digital dash reading 175mph (280km/h), I had my bum pushed back against the seat hump as far it would go, with my chin on the fuel cap as I tried to get tucked in, desperately trying to give my shoulders some respite. But there wasn’t much. The Blade has certainly slashed some bulk from its flanks.

While it’s fast, the power is useable, the torque linear, and the wheelie happy old Blade has gone. There are no peaks and troughs in the power curve like before, just one continuous drive to the 13,000rpm redline, 750rpm higher than before. On paper the new Blade might be down on peak power compared to the competition – Honda isn’t boasting the magic 200hp figure like some manufacturers – but the designers say that you don’t need power, you need control. And the 2017 model makes use of every last pony with superb chassis composure and handling.

At the end of the straight there’s a slight pulse from the ABS through the lever, as the new Brembo calipers eat away at your speed. Unfortunately, the ABS can’t be deactivated and at times was a little intrusive for hard track riding. The clutch lever is dormant once you’ve pulled away – the auto-blipper combined with the engine brake assist do the work for you on downshifts, the quickshifter firing in the gears on the ups. The semi-active 43mm Öhlins fork takes the strain as you flick the Blade onto its ear with less effort than before, and the standard A1 track setting is impressive.

Hit the apex, knee brushing the track, and you can simply crack the throttle and trust the excellent electronics to control the wheelspin and hovering wheelies on the exit. It’s excellent. It takes a while to place your faith in the electronics, but once you’ve felt them save a slide or control a wheelie you have the confidence to lean on the rider aids, and let them do the head work. They aren’t intrusive, and have been developed to improve your lap times, not hinder the fun. If you’re too aggressive with the throttle they will cut in abruptly, but you soon learn to tickle the edges of grip until the clever electronics help you push past the limit.

You can tweak the electronic rider aids to suit your riding and the conditions, too. I eventually opted for full power, engine braking on its least intrusive setting, and torque control (traction control to me and you) on its lowest setting. You can even change how rapidly the quickshifter makes its changes. While it’s a hugely impressive system, you can also switch everything off if you wish. The old Blade didn’t have any rider aids, but in a single model update Honda has delivered some of the best on the market. And if you think that is impressive, wait until you get to ride the semi-active Öhlins suspension.

There are three preset semi-active settings: A1 for track, A2 for fast road, and A3 for comfort. As we rode the new Blade on track (on Bridgestone slicks) we focused on the A1 semi-active track setting. In this mode there is a default set of parameters, but you can further tailor them to personalise the suspension. This is when most people switch off as suspension set-up can be confusing, but Honda has simplified it on this bike.

You can improve the suspension in four ways: General, Brake, Corner and Acceleration. Within each of these categories displayed on the full colour dash you can change to plus five or minus five. For example, if you want improved braking support you add to Brake, to improve the bike through fast direction changes, give it another notch of Corner, and if you require better acceleration, ditto under Acceleration. If that is too much you can reduce it again. You can change these settings while on track but I preferred to come in, select my levels, and head back out again before the slicks had time to cool. In a 45-minute session I was in and out of the pits seven times trying different settings, and if you make a complete mess of it, it doesn’t matter – simply revert to the Honda defaults, which actually work really well.

I was blown away by the simplicity and the degree to which you can change the SP, not just the suspension but the rider aids also. If you’re feeling tired, increase the rider aids, add some wheelie control and then soften the suspension slightly, it takes moments. Once you’re used to the buttons and the layout you have a very powerful and versatile system at your fingertips. Honda has created one of the easiest bikes to tailor to your needs and skill level, and it’s very impressive.

And for those who still want to adjust their suspension using conventional parameters, Honda offers three standard modes: M1 Track, M2 Winding and M3 Street. You can add and reduce compression and rebound in five per cent increments, and again there is a default setting if you get it wrong. In manual mode the suspension is not semi-active, but it can be changed electronically on the move by the rider.

To think the old bike had no rider aids and had remained essentially unchanged since 2008, this is a big step forwards for the Blade. While it was still fighting for wins in the WSBK and TT (and still managed to win the title here Down Under) it was struggling to match the competition.

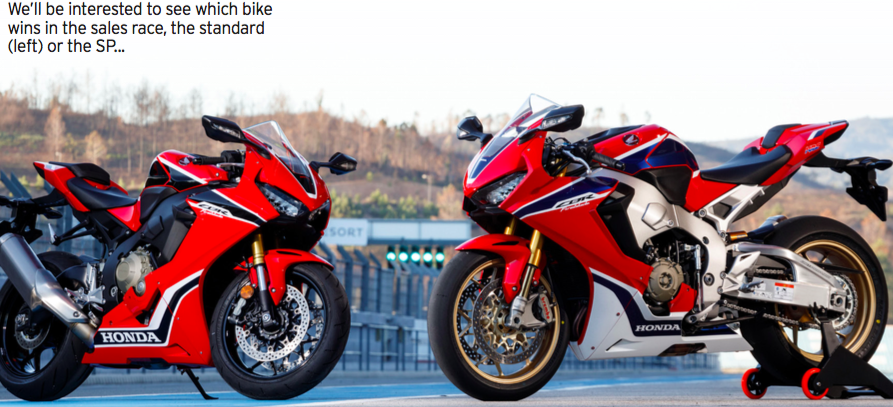

After hopping off the SP, it was time to test the more affordable ($22,499 + ORC) standard version. So was it a big step down? Not as much as you might think.

The standard Blade has the same power, torque, delivery and ride-by-wire throttle as the SP, the excellent rider aids are identical, and the RCV213V-S-style full-colour multiple-display dash is the same. The bodywork is identical, the riding position, the lovely exhaust note – one of the best sounding in-line four stroke bikes I’ve ever tested – you guessed it: the same. So what are the differences, apart from the paintwork and a six grand saving?

Crucially, the standard Blade comes on conventional fully adjustable Showa suspension, which although not semi-active, is still impressive top-spec kit. The fuel tank is made of steel rather than titanium, the quickshifter/autoblipper is optional, and it comes on Bridgestone S21 tyres, rather than the SPs RS10s.

The stock bike is only 1kg heavier than the SP, and the feel from the Showa suspension is excellent – you can sense the torque control intervention aiding your exit speed as the road-legal Bridgestone S21 eventually struggles to cope with the full 141kW. At first I personally preferred the standard model on standard tyres as it’s easier to reach the level where the rider aids help out. It’s like skydiving and pulling the parachute early – you already know the safety net is there.

But after a few sessions I wanted a little more support from the rear on the initial stroke, as it has a tendency to squat under acceleration, which puts extra strain on the standard rear Bridgestone. However, I could have easily come into the pits, and dialled in more support.

Up front the big piston Showa fork felt superb, and with the same cornering ABS as the SP you can trail the brakes deep into the turn. The front is excellent, as is mid-corner grip, and within 10 laps I was into elbow-down levels of lean on road-legal rubber. Just because this is the base Blade you shouldn’t think it’s a tribute band – it’s the real thing, just missing the clever easier-to-adjust and navigate Öhlins semi-active suspension. But I’d wager that once it’s perfectly set up on the same rubber as the SP, the lap times would be near identical.

Back in the pits after the test, I had a moment to look at the two bikes side by side. The SP has more wow factor and is more desirable, but it’s not like the standard bike is an ugly sister. Bling aside, they’re equally good looking. You don’t have the versatility and simplicity of the SP semi-active suspension, but add the optional quickshifter and you won’t be disappointed. As impressive as the SP is, if your confident in suspension set-up, or aren’t addicted to trackdays, then opt for the standard model and save yourself a serious chunk of cash. Just don’t park up next to an SP.

Overall, both new versions of the Blade are smaller, lighter, quicker, but still stable and easy to ride. The rider aids are some of the best on the market, with a huge spectrum of adjustment that caters for novices and experts alike. The semi-active Öhlins suspension on the SP is more advanced than any other system on the market – and Honda has finally made adjusting it easy and understandable for everyone. Experienced riders will find the cornering ABS a little too intrusive, and it’s hard to get everything tucked in behind the small bodywork, but this is a hugely impressive transformation for a racetrack stalwart.

The Blade has been languishing in the corner of the litre class for the last few years, but now it’s ready to take centre stage.

TEST ADAM CHILD