So who was the original 70s biker chick?

In 2016 the models sashayed down the Paris Fashion Week runway, setting the catwalk on fire with their leather trousers and dungarees, campfire ponchos and kaftan-styled dresses.

The fashion writers went into overdrive last year as models from the conservative Chloé fashion house rewrote the rule book for casual elegance.

“There is still a silk scarf tied at the throat but combined with the leather and the flat boots and worn by models who scowl rather than decoratively pout, they take on a new highwayman swagger,” wrote one battle-weary observer.

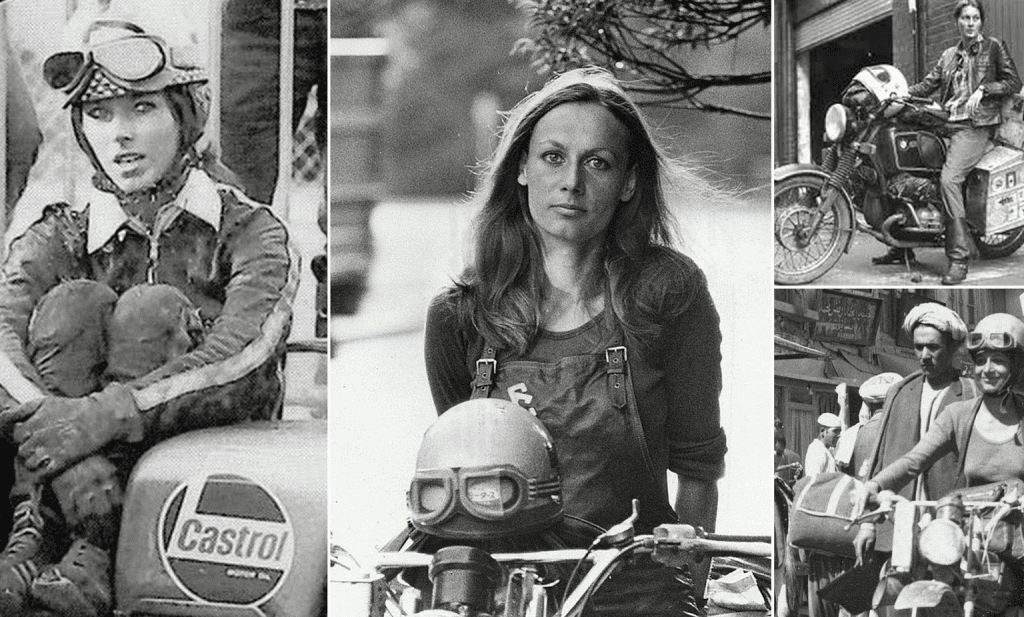

The inspiration for all this cheeky chic was an original French biker, the endlessly photogenic Anne-France Dautheville. From 1972 to 1981 she rode around the world, eventually writing a book entitled And I Followed the Wind.

A year on, female biker fashion is booming. Vogue calls it “tough girl leather”, Glamour magazine says “it’s fashion that you’ll want to wear even if you are sans wheels”, and Just the Design fashion blog urges women to “rev up your wardrobe”.

It’s enough to give those original seventies biker chicks the heebie jeebies.

Back in those days they had to endure the slings and arrows of male scepticism stirred up with an ingrained chauvinism. Now they have to endure another form of it that involves being damned with praise.

A Paris Fashion Week designer tried to explain: “I was looking to take the Chloé woman somewhere else, somewhere tougher, more daring, more gritty. I was looking at motocross images and I found this amazing woman. She had such independence of mind, of spirit.”

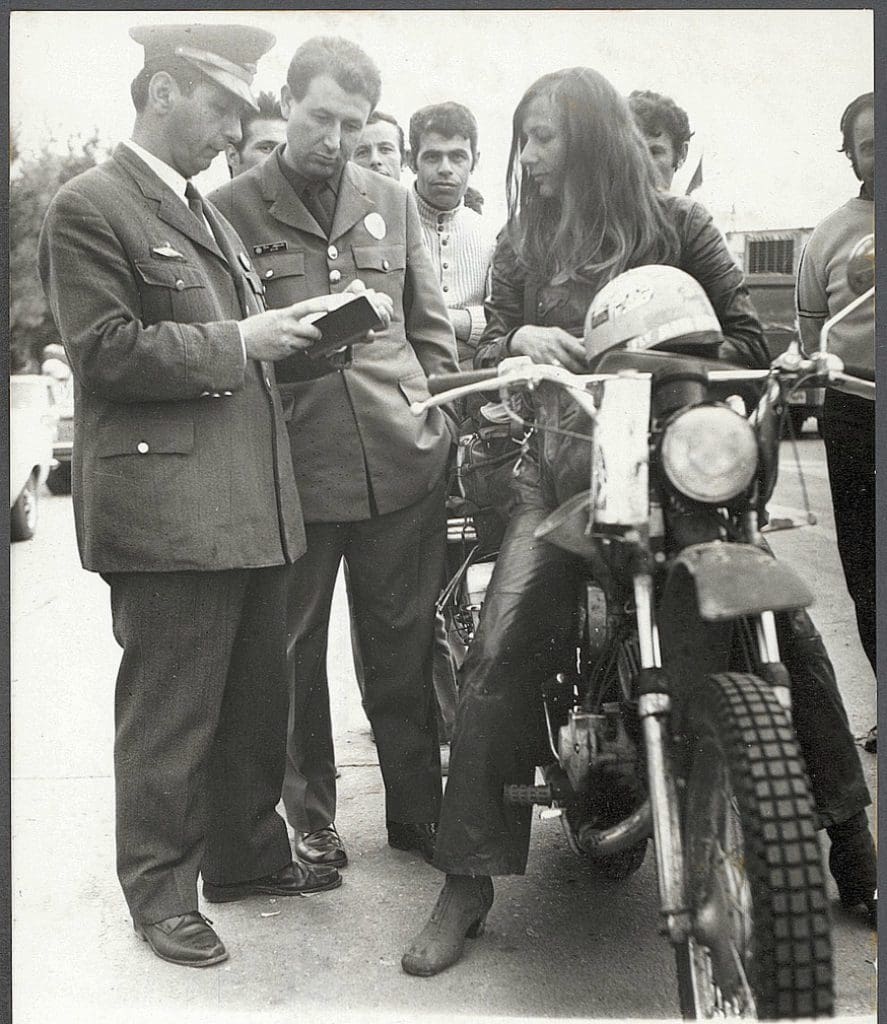

That was Anne-France Dautheville. In 1972 she threw off the shackles of convention to ride a Moto Guzzi from Paris to Tehran.

A year later she rode a Kawasaki 125cc two-stroke 20,000km across three continents.

A former advertising copywriter, Dautheville certainly wasn’t camera shy. She appeared very comfortable being the centre of attention, as the slew of photos any Google search of her throws up will testify.

However, she has a different attitude today. In a recent interview with the New York Times Style magazine she said: “I am a normal woman. I am not exceptional at all. I’m not especially courageous, I’m not especially strong … it was the first time an average person could do all these things.”

True, the seventies were a time women felt a freedom to do exactly what they chose. But there was another period this happened – the 1930s.

That was an equally defining period for women. They seized their place in a fast-changing world powered by new technology, including motorcycles.

Dot Robinson, born in Melbourne but raised in the US, raced motorcycles against men and eventually co-founded the world’s first female-only motorcycle club, the Motor Maids of America.

Over in Germany, Ilse Thouret was also racing motorcycles and winning, as well as working on them. What her high society parents thought of this is not recorded.

As the clouds of war blacked out that decade, women found a new place in motorcycling: dangerous dispatch riding for the Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service). More than 100 lost their lives doing this vital work.

After the war a new consumer society created a household revolution funded by the male with the woman in a supporting role. That lasted two decades until this rule book was torn up in the Swinging Sixties, giving people like Anne-France Dautheville her moment in the sun.

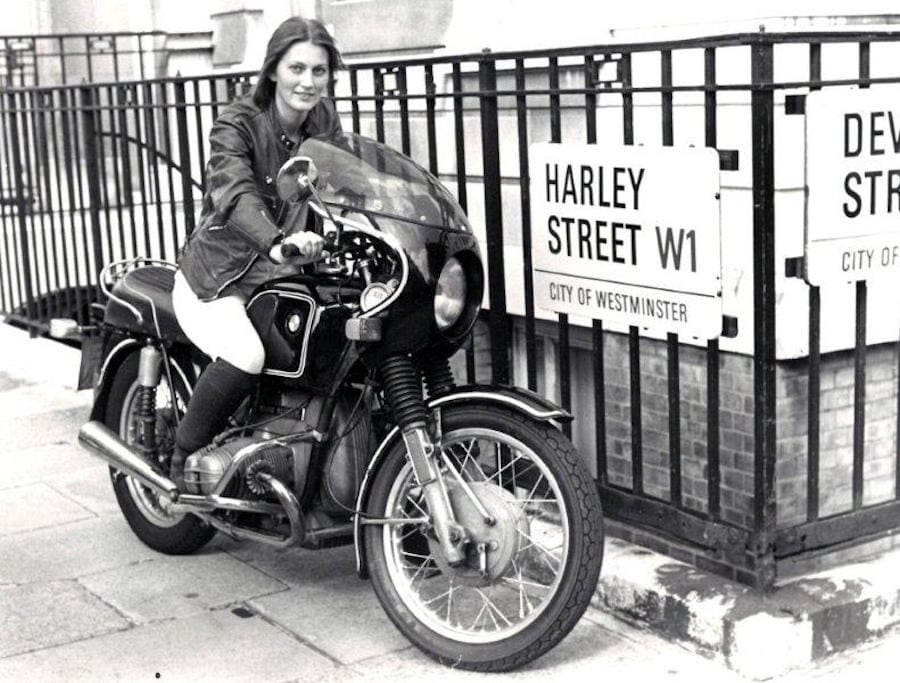

After her came the equally elegant Elspeth Beard, a British motorcyclist who rode her BMW twin around the world in 1982.

Last year BMW asked what the solo ride had taught her. “I learnt that there was never a problem that I couldn’t solve,” she replied.

Her final advice to the interviewer?

“Just get up and go. Do not overplan things. Because if you overplan, you will always find 10 reasons to stop you from going.”

Perhaps Elspeth should have added: It takes more than a leather jacket to make a motorcyclist.

By Hamish Cooper