As far as motorcycle sport comebacks go, this will take some beating. The reborn Indian Motorcycle company recently returned to flat-track racing after a 60-year hiatus to resume hostilities with Harley-Davidson. In less than a year, the Minnesota-based company has committed to compete in America’s national flat-track championship.

It built two racebikes from the ground up and entered the final round of the 2016 season with 47-year-old ex-champ Joe Kopp on board. In brutally dangerous conditions, Kopp won the Dash for Cash, a kind of Superpole for the six fastest qualifiers held over four laps of the mile-long track. He then got the holeshot in the 25-lap, 18-rider main event and eventually finished a gruelling seventh.

This all played out in front of a nearly full grandstand of cheering fans at the Santa Rosa Mile, an event staged on a horse track in Northern California. That night, with exquisite timing, Indian announced its new ‘Wrecking Crew’ team for 2017: Bryan Smith, Brad Baker and Jared Mees. Between them, the trio has won every championship since 2012. It’s like Norton returning to MotoGP, setting pole with Carl Fogarty at its debut race then signing Rossi, Márquez and Lorenzo. That noise you can hear is foreheads hitting desks at Harley HQ.

If all that doesn’t stretch credulity, the day after the bike’s competitive debut I’m stood in the parking lot pits at 8am waiting for my turn to ride the new Indian Scout FTR750. While it’s had seven development tests with pro racers, I get to ride it before at least one member of the new team, since Brad Baker is contracted to Harley until 31 December.

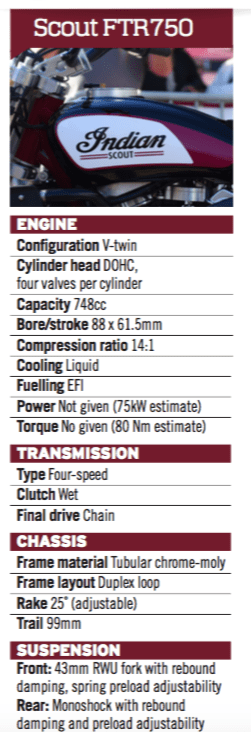

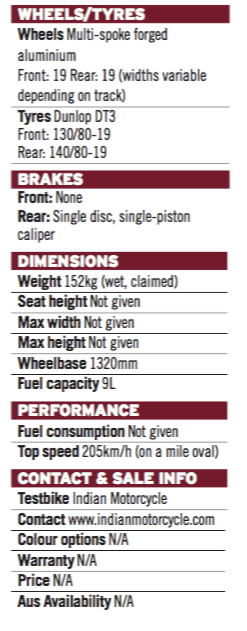

An engineer picks up a remote starter, slots the 3/8ths socket drive through a hole in the left- hand engine cover into a square socket on the end of the crank, presses a button and spins the bike into life. Twin high pipes running under my left thigh bark with a hard-edged, high tickover.

The FTR750 has the brake and gear lever both on the right side, one above the other. This is a flat-tracker, so there is no front brake. The foot pegs are also asymmetrical, the right being much lower than the left.

I lift my right foot off the peg to firmly stamp the bike into first and roll away. Short shift to second, then again to third while riding across the corrugation of ruts in the middle of the track, aiming for the cleanest line at the bottom of the wide corner. The track is a mile-long oval, big enough to have a golf course in the middle.

In places the inconsistent dirt offers the same level of grip as an eel dipped in diesel.

At first glance the bike might look like something from 1971, but it has sophisticated fuel injection and featherlight pistons. Revs rise and drop more like a fit two-stroke than an American V-twin. It spins to 11,500rpm, 2500rpm more than Harley’s dated but still potent XR750, and has an incredibly flat torque curve of around 80Nm from 6500rpm to north of 10,000rpm. Dirt-track racers tend to run the whole race in one gear, usually top of the four- speed ’box.

Unofficial but informed talk says the engine could deliver 93kW, but Indian’s development engineers point out that the rear Dunlop is a 52kW-rated tyre. Power isn’t the crucial aspect of this sport anyway – power delivery is. So while the rest of bike racing is trying to shave more grams off their wheels and reduce all other unsprung weight, Indian has designed heavier rear wheels to reduce wheelspin.

It also made the engine so that it’s quick and can easily have weights added to the crank to increase rotational mass, absorbing energy and increasing rear traction. The flat torque curve means that if the tyre does spin up, and revs rise, it doesn’t deliver more torque and compound the problem. In fact, just about the whole engine has been designed with traction as the primary consideration. Traction and reliability. The engine is designed for 30-hour service intervals.

“Using the Scout production motor wasn’t a bad idea, but would it give us every single chance to win every single race? Every decision has to be made to aid winning races.” That’s how Gary Gray, Indian’s product director, explains their approach. “So we decided to build a ground-up brand new engine, because that’s going to give us the best chance to win.”

You could fit the total parts it shares with a road Scout in your shirt pocket. Even 10o of throttle twist has the rear tyre stepping

out. The engineers, obviously new to letting journalists ride their handbuilt racebikes, haven’t remapped the ignition to knock off some of the power. Fools. Today’s test bike, the spare racebike, is set up exactly the same as the one used by Joe Kopp barring a one-tooth different rear sprocket and a different design of the rear wheel. The headstock of the bike I’m trusted with is stamped FTR0001.

Everyone is very cagey about figures, but 75kW is a reasonable guess for current rear wheel horsepower. It had the jump on every other bike off the line in yesterday’s race and led the first lap before Kopp’s own fitness and self- preservation saw him overhauled by younger men and championship contenders.

I have a steel shoe strapped to my left foot and skim it firmly on the ground, ready to push down if the rear wheel lets go through the wide corner. The FTR750 weighs a few kilos more than the class’s lower limit of 136kg, but somehow the weight has disappeared. At odds with current road racing orthodoxy, the alloy nine- litre tank fills the front half of the carbon-fibre cover. Behind it is an air filter for the downdraft intakes. There is no fancy airbox.

The wheelbase is short, the rake steep. The FTR750 inspires dreamers to yelp, “Why doesn’t Indian put lights on this and sell it?” The answer is it’s so twitchy it would make a disastrous roadbike, but its design cues might make it through to production in the future.

Under acceleration the front wheel rolls over barely visible ripples and the ’bars wiggle in my hands, threatening a tankslapper. This bike is set up on the edge of stability. I fight the natural reaction to hold on tighter and order myself to wind the throttle further than the last lap. These journalist track tests, involving knobbers like me on brutal machinery, are a disaster flirt,

like cage-diving off the Cape Town coast after feasting on sardines.

When I rode Casey Stoner’s Desmosedici it felt like it would make an incredible roadbike, flattering mere mortals with its grip, brakes and speed. The FTR750 is the opposite. We’re not in this together. Yes, it will tootle around at 60km/h, but using even two-thirds throttle makes it misbehave in all kinds of ways. It is geared to reach 205km/h at the end of the quarter-mile straight with the right man on board, but outright top speed is irrelevant to the job at hand. Still, if I ignore the squirrely twitchiness the rest of the package is remarkably civilised. Fuelling is as perfectly usable as the very best roadbikes, and it pulls from low revs without a hiccup. I don’t notice any harsh vibrations since the liquid-cooled, 53o V-twin has counter-rotating balancers.

The chassis is tubular chrome-moly, with a direct-acting Racetech rear monoshock. At the front, a conventional Yamaha R6 fork that dates back to 1998 is chosen because it’s widely understood by flat-track suspension specialists. The swingarm pivot position is adjustable – as are the fork yokes – for rake and offset. Chain adjusters are extra-long to offer more wheelbase options.

I have two sessions on the Indian and after the first I can feel the adrenaline wash through my torso to my feet like a toilet cistern emptying. My hands start shaking as I pick up my pen. In the next session I have both tyres moving through the turns. The outside of the corners is deep sandy dirt, the inside looks like hard-baked mud with a morning dew of powdery dust. The wide, mile-long horse racing oval took a beating yesterday. It is a rutty potholed mess and two promising GNC2 riders (the flat-track equivalent of Supersport) crashed and died here less than 24 hours ago.

I raise my head and look down the track, aiming into the black shadow thrown by the huge grandstand, and wind on the throttle. At perhaps 7000rpm, the potholed corner entry is approaching fast. The brake lever is much further forward than I’d like, so

I rely on engine braking before accelerating through the wide, gently cambered corner and onto the back straight for the last time.

I would love to ride it for the rest of the day, allowing myself to steadily increase speed and confidence, but that’s never going to happen. Bryan Smith, the newly crowned 2016 champion, is coming to test the bike 10 minutes after I’ve finished experiencing it Indian has been clever in entering a sport that is underfunded, but still has plenty of relevance to its brand. Indian’s chiefs won’t talk budgets, but say it’s less than most people would think. They’re hoping that race success will drive people to showrooms to test-ride Indians, and they think their roadbikes will do the rest. Few are doubting it can win on Sunday; Indian dealers will have to do the rest.

Hooligan racing

WHILE THE SCOUT FTR750 shares little except a fuel pump with the roadbike, Indian has been marketing the hell out of its Scouts with a mini-fleet of ‘hooligan’ racers built by Roland Sands Designs using the Scout Sixty. Tonight I get to race one on a tiny dirt track that would easily fit inside a school gymnasium.

Eighteen bikes line up in three straight rows. To enter this Hooligan class, your bike needs to be over 750cc and have a stock frame. My Scout has 19-inch wheels, Dunlop dirt track tyres, a 2-1 pipe, dirt-track style carbon fibre seat, motocross-style ’bars and a ding in the tank the size of a Yorkshire Terrier. While it is fitted with a front disc, it has no brake caliper or lever.

The track is loose dirt, and the six-lap heat race is a fistfight in a phone booth. I finish third and make the second row of the final. There seems to be way too many bikes on

the track for the final, but the crowd is howling its approval.

The first corner is, predictably, carnage. The race is red-flagged after Roland Sands crashes in the first corner and is ploughed into by a Harley Sportster. He curls up on the track.

Despite its 250kg mass, the RSD Scout Superhooligan is incredibly easy to ride hard. After only four laps of practice I’m confidently locking the rear tyre into the corners and gassing it, crossed-up on the way out. After a year of familiarisation, Roland rides the bike like a modern 450 single.

I’m no match for most of the locals who’ve been racing their hooligans all year, but I pass a few and walk out smiling. I woke up that morning only thinking of survival. The Scout Superhooligans are so much fun to ride, I left disappointed that I didn’t do better.