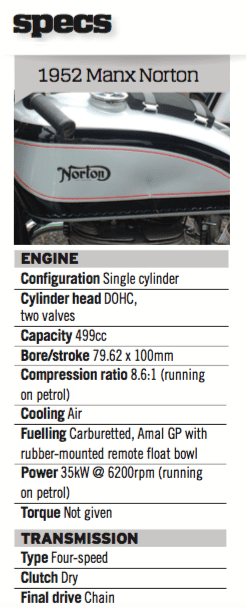

Maybe it’s the styling: silver paint set off with black striping; a humped-back seat with red piping: a small flyscreen set above low handlebars.

Maybe it’s the noise: A BARRUUMMMBA, BARRUUMMMBA roar that only a single-cylinder racer with an open megaphone can make.

Maybe it’s the stories: tall tales and true from the Continental Circus.

Make no mistake, the Manx Norton is a mythical motorcycle. It was the backbone of privateer racing for two decades and was seen on grand prix grids long after the little British single had passed its used-by date. Manx Nortons were still scoring world championship points in 1971.

Let’s look at the Featherbed Manx that started all this – a rare long-stroke 1952 model.

TIME MACHINE

This particular Manx was made in the second year of production of the over-the-counter customer version of the famous 1950 works Featherbed single-cylinder racer.

But time doesn’t stand still. Even though the 1952 Manx was considered a benchmark of British engineering and displayed superb handling characteristics compared to its rivals, the factory was about to reconfigure the engine. A short-stroke version, providing more power at higher revs, was introduced in 1954 to replace basic DOHC engine architecture that dated back to 1937.

Privateers soldiered on with the earlier versions for several more years. And over the 1950s, major upgrades to suspension, brakes and the gearbox saw the Manx evolve into a different and faster beast. This 1952 long-stroke model is fairly rare.

RIDE ON TIME

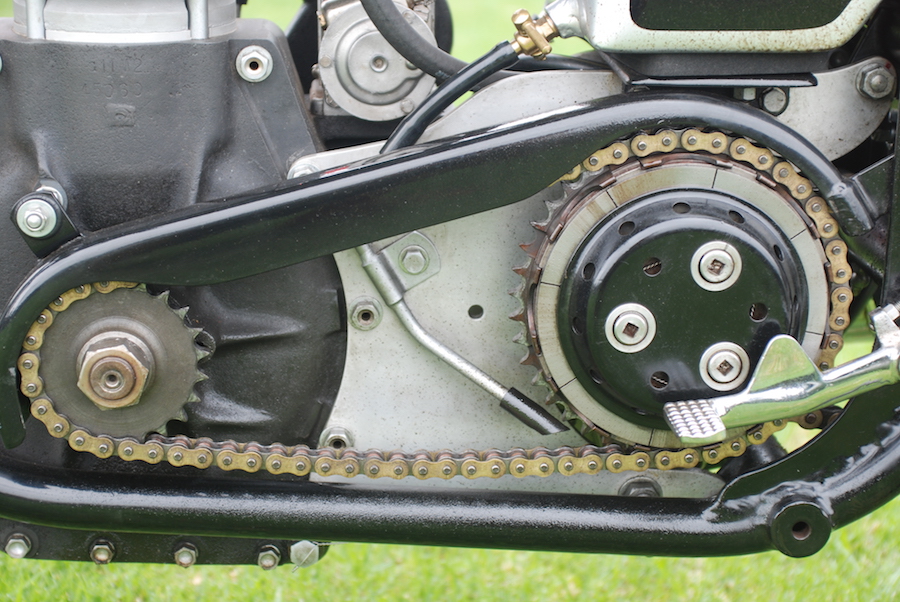

Riding this Manx opens a window into another world of racing machinery and how it operates.

As soon as you sit on it you realise how this new rolling chassis propelled Norton into the future. It must have been a revelation for riders used to the sprung saddles of a typical roadbike converted into a racer.

The Manx seat is roomy and the suspension also is a leap ahead, and settles gently under you as the hydraulic front and rear units take up the weight.

Starting the Manx is a bit of an art. To flood the carburettor you tap the rubber-mounted remote float bowl with two fingers until it floods, while leaning the bike to the right. Pull the rear wheel backwards until you have the engine over the compression stroke, then either push-start or spin it up on a set of mobile rollers, holding the throttle open just slightly.

After it fires it’s easy to kill the engine with too much air as there is no choke on the racing carburettor. You have to rev it gently, resulting in that famous Manx exhaust note. The magnesium crankcases warm up surprisingly quickly and the smell of castor oil soon wafts up from the exposed valve springs on the top of the engine.

First gear is very tall and you need plenty of revs on hand and a deliberate fanning of the clutch to get cleanly off the line.

Once over 3000rpm, power builds briskly without the sudden step you might expect of a racing engine. For those who have never ridden a Manx, the power characteristics of the long-stroke engine make it similar to punting an old Honda XR600, except that it vibrates more.

Power peaks at 6200rpm with around 28kW being pushed through the rear tyre.

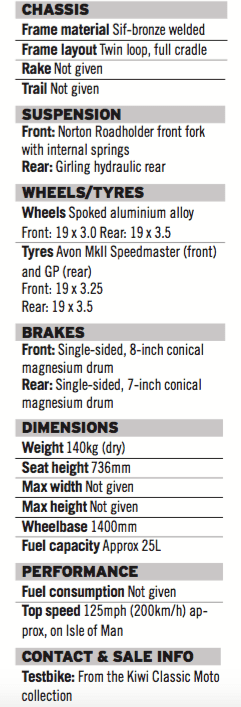

You’ve only four gears to play with and, apart from first, they are all close together. But if you change up at maximum revs, you stay in the powerband, the rear suspension squats and the front forks go light. Gearbox action is as good as a modern motorcycle and the chain-driven clutch is surprisingly light in operation.

With a dry weight of around 140kg and a willing engine, the Manx is quite fast. The chassis tracks true and straight through corners and the harder you ride it the better it feels.

There are some shortcomings, though. The damping on the early version of the famous Roadholder front fork isn’t as effective as on later versions. The bike can skip over bumps and the effect is possibly amplified by the wide, swan-neck, clip-on handlebars.

The single-leading-shoe front brake feels minimal, compared to the later double-sided twin-leading-shoe units.

The riding position may have been a huge step forward for the day, allowing the rider to tuck down behind the flyscreen, but now it feels more like a modern sports-tourer.

As you return to the pits, you are slightly overwhelmed by the whole experience – the sound of the exhaust megaphone, the smell of the oily engine, the admiring stares of the spectators watching a legendary motorcycle go past. It’s the feeling of entering a time capsule from a famous moment in British motorcycling history.

Give me five

Jack Ahern says the best thing he ever did to a Manx was fit a five-speed gearbox. These Austrian Shaftleitner units were horrifically expense but Jack bought two of them when they first came on the market in 1962. Around this time the Norton factory made the final update to the Manx, fitting double-sided twin-leading-shoe front brakes, improving oil circulation, and making some minor improvements to the engine. In 1963 the factory stopped Manx production and Colin Seeley bought the remains of the race shop.

Words and photography: HAMISH COOPER

Jack Ahern stuck with Manx Nortons in 350cc and 500cc forms throughout his career. He started off at the Isle of Man and Grand Prix events on the long-stroke version.

[captions]

Various static shots of the Manx, showing single-sided front brake, single-row primary chain, laydown gearbox with remote gear linkage.

Hamish Cooper rides the Manx.

Kevin Schwantz’s father, Jim, prepares to ride a long-stroke Manx at a vintage race meeting.

The precursor to the DOHC is this SOHC pre-war version.