THERE can be few more improbable road racing champions than Beau Beaton, winner of the 2015 Australian ProTwins/Nakedbike Championship. Aboard a big-engined Irving Vincent, Beaton defeated fields of Ducati Panigales and Aprilia RSV Tuonos to wrest the title from defending champion Angus Reekie on his importer-backed KTM 1290 Super Duke R.

It’s always nice when the underdog triumphs, though in this case it also proved that, done right, there’s still no substitute for cubes. Those poor little 1199cc Panigales, used to beating up 1000cc fours in Superbike racing, had the tables turned by the Irving Vincent, with a pushrod motor measuring a whopping 1571cc for 142kW at the crank at 7250rpm, in a bike scaling 175kg with oil, but no fuel – or water. “Water’s just what we use for washing the bike,” grins constructor Ken Horner.

Ken and his brother Barry are builders of the succession of potent, torquey and exquisitely engineered Post-Classic Period 5 1300cc Irving Vincent V-twins that have raced so successfully since 2003 (see sidebar).

But this isn’t the first time the Horners have stepped up to compete against modern hardware with their improbably fast neo-vintage creations. In Daytona’s Cycle Week 2008, Craig McMartin hopped aboard their first cubed-up 1600cc two-valve V-twin, which had turned a wheel for the first time just seven weeks earlier. He rumbled away from a grid of liquid-cooled multi-valve Superbikes ridden by the likes of Doug Polen, and won the world’s premier ProTwins race held on the famous Florida banking. That was the team’s first appearance away from home.

Six years later they repeated that success by racing in Europe for the first time with a historic motorcycle from the other end of the Vincent marque’s timeline – Beaton and McMartin teamed up to score victory in the 2014 Goodwood Revival aboard the Horners’ 1948 Vincent Rapide.

In search of another challenge, Ken and Barry then decided to upgrade their Daytona with an eight-valve head, fuel injection and Öhlins suspension, having been enticed to compete in the 2015 ASC ProTwins/Nakedbike series by promotor Terry O’Neill.

“We had problems getting the Post-Classic authorities to recognise that we needed some help to be competitive with the much faster four-cylinder P5 bikes via a capacity differential,” says Ken Horner. “The modern Superbike class has a 1200cc ceiling for twins against 1000cc fours, but they wouldn’t give us something comparable for Post-Classic racing, so we didn’t race at the Island Classic last year.

“But Terry O’Neill recognised the benefits of having an Australian-built motorcycle on the ProTwins grid, and went out of his way to encourage us to compete in that. So we built up the eight-valve version of the 1600 motor into a modern race frame and started work on developing that. We did okay in the end by winning the championship, but it was a long, hard road to make it reliable and handle properly.”

I’d given the eight-valve bike a trial run back in 2011, but it was unraced until November 2014, when a key issue was revealed: producing that much power from an air-cooled engine running on petrol resulted in overheating and major detonation problems. A pre-season application to O’Neill led to air-cooled motors at his events being permitted to run E85 fuel – a blend of 15 per cent petrol and 85 per cent ethanol – which made them run cooler.

In that guise the jumbo Vincent was immediately competitive. In the opening round at Sydney Motorsport Park in late March, Beaton finished second in two of the three points races before turning the tables on KTM’s defending champion Angus Reekie for a debut win.

The second round at Mallala in May was a shocker, Beaton sliding off twice as a result of handling and braking issues, but at least Reekie had failed to score after crashing the KTM.

Suspension guru Steve Mudford of Race Dynamics helped sort out the suspension issues and, while an unsuccessful experiment with an even bigger 1618cc version of the motor (achieved by boring it out another 1.5mm) spoiled one other race meeting, Beaton came out on top after seven rounds and 21 races, ending the season as champion with 383 points, ahead of Aprilia-mounted Kris Keen on 312.

To transform their dominant methanol-fuelled 1298cc Post-Classic engine measuring 100mm x 82.5mm into a cubed-up ProTwins contender running on E85, the Horners used the same heavy-duty crankcase – complete with provision for fitting a starter motor and alternator in case the brothers cave in to pressure and build an Irving Vincent 1600 streetbike.

This externally faithful recreation of the 50-degree V-twin high-cam Vincent dry-sump motor was stroked to 100mm for 1571cc, with a plain-bearing crank, Carrillo steel rods and Nikasil-bore cylinders housing full-skirt JE three-ring flat-top pistons made in California to the Horners’ design, running 13:1 compression (versus 12.5:1 for the smaller engine).

The long-stroke crank weighing 8.4kg was milled in Hallam from a solid billet of EN26 steel that started out scaling 80kg – that’s a lot of swarf! – and carries Timken taper-roller bearings on the drive side, with an INA roller bearing on the timing side. The 48mm crankpin runs Clevite V8 Supercar bearings – just one example of the crossover technology employed in creating the Irving Vincents. “Especially in terms of cam profiles and combustion chamber design, we treat it as one-quarter of a V8 Supercar sedan’s race motor,” says Ken Horner. “That way we can plug into the acquired knowledge of all the people we know who work on those engines.”

While the Daytona-winning engine’s two-valve heads carried 53.4mm inlet and 41.9mm exhaust valves made from titanium, sourced from key NASCAR suppliers, the eight-valve version paired 41mm titanium inlet valves and 34mm exhausts made from Inconel, a special heat-resistant alloy mainly used for exhaust systems. When you’re producing this much power from an air-cooled motor, heat is obviously an issue, and engine performance is very temperature sensitive.

“On a long dyno run, you can see the power disappear as it heats up,” says Ken Horner. “We had to completely redesign the oil system to produce serious power reliably. Phil Irving used to say the original Vincent’s lubrication was so poor – and he took the blame for it – that if you could see inside when it was running, you’d see sparks coming from the cam lobes! We had to make sure we pumped a lot more oil than back then, especially with the plain-bearing crank.”

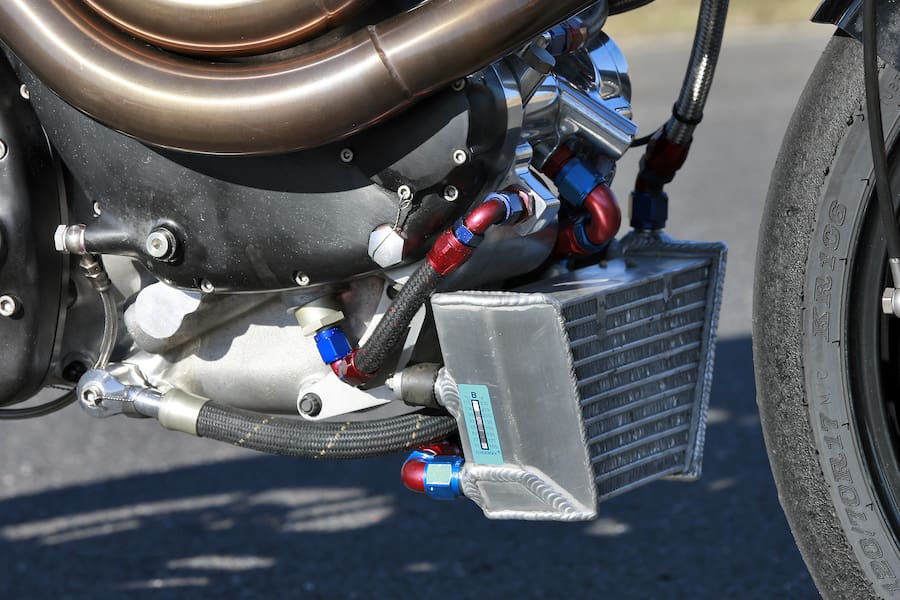

The Horners have done this by installing a two-stage oil pump in front of the engine, where the magneto normally sat on the original Vincent motor, to take care of both pressure and scavenging functions. “The extra heat we generate from the exhaust ports on the four-valve heads originally caused some valve failures on the dyno,” Ken says. “Using Inconel for the exhaust valves seems to have fixed that.”

While the brothers were originally disappointed at the ‘mere’ 11 per cent increase in horsepower from 109kW to 121kW obtained by stroking the 1300 an extra 300cc, it was good enough to beat the liquid-cooled Superbikes at Daytona. And while the eight-valve motor produces more power at the crankshaft via an 18 per cent increase in revs, the Horners have also increased the jumbo V-twin’s already massive torque, which is now 197Nm at 5800 rpm, up from 176Nm at the same revs on the Daytona-winning bike.

The five-speed gearbox is based on a Quaife design with pinions entirely cut on KH Engineering’s CNC machines at Hallam, but with an RD350LC Yamaha selector mechanism matched to KHE selector forks and drum, and a multiplate oil-bath clutch with Kawasaki plates and a straight-cut gear primary drive.

It was quite an honour to be entrusted with the task of shaking down this ultimate Aussie-built modern incarnation of the legendary Vincent racer on its track debut. It represents the latest example of Australasian alternative engineering that’s entirely in keeping with the Britten V1000 I found myself sharing the track with on one occasion, ridden by four-time world champion Hugh Anderson [see photo]. As the fastest pushrod-engined road racer ever built, the 1600 Irving Vincent 8V is in every way the Aussie counterpart to the Britten – a bike entirely conceived and constructed by two dedicated enthusiasts using their own resources, which ended up beating the products of established factories.

I’ve tested or raced literally hundreds of twin-cylinder road racers, but I can’t think of any such bike with comparable reserves of torque to that delivered in such a smooth but irresistible way by the 1600 Irving Vincent. With a flat torque curve from 3500rpm upwards, get it running beyond that threshold and you just surf the waves of grunt that the big engine delivers. That serious mid-range poke delivers acceleration that is so emphatic and addictive you’re best getting the bike upright as soon as possible, before pulling the trigger to max out drive. You don’t want to risk climbing the staircase to highside heaven.

Yet the big eight-valve Vincent engine is noticeably sharper in pick-up and comparatively freer-revving than its Daytona-winning two-valve sister in the way it builds revs. It pulls hard and clean up to the 7250rpm power peak, where you must shift up via a left-foot race-pattern gearchange that is positive-shifting if comparatively slow in action.

The three green shifter lights atop the MoTeC digital dash light up at 6800rpm, heralding the flash of a bright red junior searchlight to the left of the dash at 7300rpm to remind you to grab another gear before hitting the 7500rpm soft limiter. Short-shifting around 6800rpm is no problem with such a flat and meaty torque curve, but it helps the Irving Vincent hold a tight line if you drive it through the turns on the gas, rather than at part-throttle in a higher gear, in which case the front end will start to wash out.

Having said that, the 8V 1600 isn’t as torquey low down as its two-valve counterpart, so you need to keep the tacho reading above the 3500rpm mark to get seriously strong drive. But everything’s relative, and there’s no denying the Irving Vincent accelerates hard once you get it wound up, shaking the earth as it thunders out of a turn, building speed and revs purposefully to beyond the 265km/h top speed its sister was trapped at on the Daytona banking – figure on at least an extra 20km/h for this eight-valver with its more streamlined bodywork and a thousand more revs.

This mighty motorcycle’s riding position feels pretty tight, with high-set footrests to give room for lots of lean angle on faster tracks so as not to sacrifice turn speed. The bike seems relatively tall and quite rangy, with a good stretch across the 22-litre fuel tank to the high-set but wide-spread clipons, which delivered good leverage for hustling the bike through Broadford’s tight turns.

The chassis felt stable and confidence-inspiring, just like its Post-Classic sister bike, but Beaton says it took some work: “We thought the Post-Classic bike’s good handling would convert to the modern ProTwins version, but it didn’t. We had to spend a lot of time with Steve Mudford searching for a good set-up, which really surprised us. What we used on the Classic bike in terms of springs and damping doesn’t work on this one. We dropped the Superbike fork into this bike and it was quite disappointing it didn’t work straight away – it’s a really different animal.”

Where the jumbo-sized Irving Vincent really excels is on the brakes – it’s very stable and predictable, and even squeezing the front brake lever really hard downhill into Broadford’s Paddock Bend didn’t make the rear wheel lift and start street-sweeping, though I didn’t use the rear brake for fear of chatter. You can use quite significant amounts of engine braking; though the 320mm front discs and four-pot AP calipers give good bite, every bit of help in getting the big Vincent stopped is welcome.

The first time I rode it five years ago, the V8 Irving Vincent was very much a work in progress. Now, thanks to the Horners’ patient development, it has turned into a much more refined package than its Daytona-winning predecessor, with better fuelling, less vibration and above all a zippier engine with even better acceleration. Add in Beau Beaton’s determined, skilful riding talents and it’s no surprise that, once again, pushrod power rules again.

Injection

The big 1600 uses fuel injection in place of carbs, with a MoTeC ECU – conveniently, the world-class engine management company is just up the road from KHE’s Hallam factory on the outskirts of Melbourne – and a pair of 57mm throttle bodies (up from 51mm units on the Daytona-winning two-valver) made in-house at KHE, each carrying a single side-mounted Siemens injector. But there’s no airbox, which you’d think would compromise performance. Ken Horner dismisses the notion: “Airboxes all over the bike spoil the whole appearance of the engine – we should use water-cooling, too, but that would destroy the whole Vincent spirit – and we can get a good result with air ducting.”

Overhead action

The paired valves are now set at a flatter 27-degree total included angle than on the two-valve motor, running in CHE magnesium bronze valve guides sourced from a Ford Zetec car engine. They feature short 4140 steel pushrods, roller-bearing cam followers, lightweight steel rockers and vernier cam timing. The roller-bearing cams were designed by Melbourne-based Eric Gaynor, who worked alongside Phil Irving in developing the V8 Repco F1 engine in the 1960s before moving to Cosworth in the UK and then to V8 Supercars with the factory Holden team.

Classic frame

Irving Vincent uses a modern chrome-moly version of the period Vincent spine-frame used on the Post-Classic racers, with a three-litre oil tank incorporated in the backbone, but here carrying a fully adjustable 43mm Öhlins FGR900 Superbike fork, set at a 24.5º rake. This gives a 1420mm wheelbase, with 103mm of trail, resulting in a 52/48 distribution of the bike’s 175kg weight. Rear suspension is by a fully adjustable Öhlins TTX36 monoshock fitted to a box-section Vincent-type cantilever swingarm, with twin 320mm front discs gripped by four-piston AP-Lockheed radial calipers, and a 225mm rear. 17-inch PVM/Dymag forged magnesium wheels carry Dunlop race rubber, 120/70 up front and wide 195/65 on a six-inch wheel at the rear.

Specs

Engine: Air-cooled ohv pushrod 50-degree V-twin dry-sump four-stroke

Dimensions: 100mm x 100 mm

Capacity: 1571 cc

Output: 121kW @ 7250rpm (at crankshaft)

Maximum torque: 197Nm @ 5800rpm

Compression ratio: 13:1

Fuel/ignition system: Electronic fuel injection and engine management system, with MoTeC ECU, single injector per cylinder, 2 x 57mm KHE throttle bodies

Transmission: 5-speed with gear primary drive and multiplate dry clutch with AP carbon plates

Chassis: Oil-bearing chrome-moly steel spine frame with underslung engine

Suspension: Front: Fully adjustable 43mm Öhlins FGR900 inverted telescopic forks

Rear: Cantilever chrome-moly tubular steel swingarm with fully adjustable Öhlins TTX36 monoshock

Head angle/trail: 24.5 degrees/103mm

Wheelbase: 1420mm

Weight/distribution: 175kg with oil, no fuel, split 52/48%

Brakes: Front: 2 x 320mm AP/Brembo stainless steel discs with radially-mounted four-piston AP Racing calipers

Rear: 1 x 245mm Irving Vincent stainless steel disc with two-piston AP Racing caliper

Wheels/tyres: Front: 120/70-17 Dunlop KR106 on 3.50in PVM/Dymag forged magnesium wheel

Rear: 195/65-17 Dunlop KR108 on 6.00in PVM/Dymag forged magnesium wheel

Top speed: Over 280km/h

Year of construction: 2015

Owner: KH Equipment Pty Ltd, Hallam, Victoria, Australia.

www.irvingvincent.com

Creating the Irving Vincents

The exquisitely engineered Irving Vincent bikes are based on the iconic Vincent classic models. They are built as a tribute to legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving, who designed all Vincent models until the British company’s demise in 1955.

The Horner brothers struck up a friendship with Irving after he moved back to Australia in the 1970s, where Ken and Barry had both tasted success in sidecar racing with self-built outfits, in Ken’s case using a Vincent 1300 motor.

Ken, now 65, retired from racing in 1977 to start his own engineering company. He was later joined by Barry (a year younger), and today KH Equipment exports half its production to China and the US – mainly air starter-motors for the mining and fuel exploration industries where hazardous environments require sparkless function. A 24-strong workforce turns out high-precision machined components on an array of hi-tech CNC equipment. They also supply Australia’s leading V8 Supercar teams.

They have produced 18 bikes since 2003. “The engines are based on the original Vincent design, but stretched in capacity and re-engineered to correct all the original shortcomings,” Ken said. “We didn’t want to call them Vincents, although that’s what they are, because of having to pay royalties … so we decided to call them Irving Vincents, to underline Phil’s contribution to the marque, for which many feel he never got due recognition. We got approval from his widow Edith before registering the name.”

Ken produced four-valve heads inspired by Irving: “Phil had drawn up a design for one in the 60s, so we used some of the ideas he had for the rocker arm and valve mechanism, which you very rarely see in a four-valve configuration – normally on those you’ve got overhead camshafts doing the job upstairs. But we’ve made it a one-piece cylinder-head casting with a bronze skull, where Phil had looked at a billet-type two-piece head. It works pretty well.”

The original superbike

Founded in 1928 by Cambridge graduate Philip Vincent, who purchased the defunct HRD company with the financial aid of his Argentinian rancher father, the Vincent motorcycle marque lays valid claim to having produced the first true superbike. The series of 1000cc V-twin sportbikes created over the two decades from 1936 set new standards for two-wheeled performance and engineering excellence that no other brand could match.

Vincent riders scored a seemingly endless succession of race wins and speed records in the immediate post-war decade from 1946, including Rollie Free’s 1948 World Land Speed Record for motorcycles at over 150mph, obtained at Bonneville wearing just a pair of swimming trunks and lying prone on his stomach with his legs stuck out the back to reduce drag.

Designed in 1936 by the brilliant Australian engineer Phil Irving, only 78 versions of the first Series A high-cam 50-degree Vincent V-twin were produced before the outbreak of war. Redesigned by Irving for the post-war era, the Series B Vincent in standard Rapide form was the fastest and safest production motorcycle in the world. The high-performance Black Shadow variant, and especially the competition Black Lightning model, garnered an enviable reputation as the leading-edge benchmark of motorcycling excellence.

Despite introducing a host of avant-garde technical features still found on bikes today – cantilever rear suspension, wishbone forks, a high-cam engine design to reduce reciprocating weight, and monocoque frame construction using the engine as a fully-stressed member, suspended from a central oil tank – Vincent’s insistence on an uncompromising quality of manufacture and engineering was sadly incompatible with also making a profit. The company ceased production in 1955, but the bikes remain prized collectables.

TEST ALAN CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY STEPHEN PIPER