For the last 30 years there’s been a love-hate relationship between motorcycle designers and carbon fibre but the latest pearls from BMW and Ducati show the prejudices preventing its structural use in roadbikes are finally breaking down.

While carbon has long since been accepted as the ‘price is no object’ material of choice when it comes to cosmetic parts – fairings, exhausts, etc. – it’s had a troubled history when it comes to its use for structural elements like frames and swingarms. Despite attempts being made at carbon-framed racebikes dating back to the 1980s – Honda made a prototype NR500 racer with a carbon chassis as early as 1983, and Armstrong had a carbon 250 GP bike in 1984 – they’ve never enjoyed the success of bikes made of more traditional materials.

So we won’t see carbon-framed MotoGP bikes in 2017, but there will be two new production models from leading manufacturers using carbon-fibre frames: Ducati’s 1299 Superleggera and BMW’s HP4 Race. And both bikes mark a big leap forward for carbon fibre.

The BMW and Ducati are full carbon machines, using the stuff for their frames, swingarms and wheels, as well as the bodywork. Both are exceptionally light and offer incredible power-to-weight ratios. Both will be handmade in tiny numbers and sold to the wealthiest of enthusiasts for eye-watering amounts.

These toe-in-the-water carbon ventures might seem irrelevant to most of us. The Ducati 1299 Superleggera will cost around $120,000 and the BMW isn’t likely to be a lot cheaper, so why should we pay any attention? Well, because, as with any new technology, it’s likely to quickly filter down to models that are much more attainable.

And it’s not just limited to premium European brands – other firms have their eyes on the possibilities. Honda is known to have been working on motocross bikes with self-supporting carbon-fibre seat units, and developing the means to mass-produce such parts, and from that it’s only a step towards further mainstream carbon machines.

BMW’s patents have also revealed that the firm has ideas for carbon-fibre trellis frames, purely made from straight extrusions of carbon. That suggests it will eventually use the material to replace steel on bikes like the R-series boxer models.

Provided the 1299 Superleggera and HP4 Race are successful in sparking the imagination of riders and creating a desire for more carbon fibre offerings, it seems certain that the future for lightweight motorcycles is in composites rather than metals.

HOW SOON?

BMW

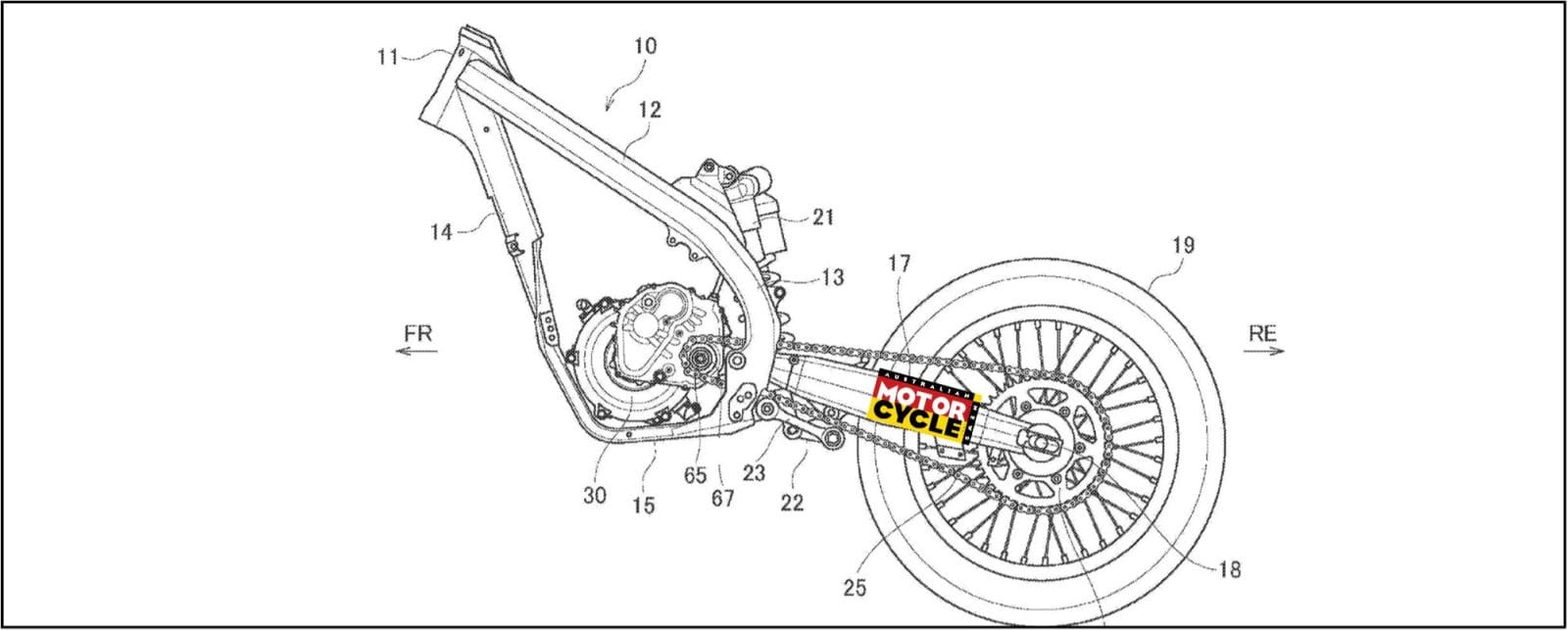

BMW’s official line on the HP4 Race, which has only been shown as a prototype but is promised in production form before the end of 2017, is that it’s to be handmade in small numbers. But the company’s own patents have already betrayed its intention to bring the material to the masses. More than a year ago we revealed the company’s plans for factory-made carbon frames, including a beam frame design that looks near-identical to the one on the HP4 Race prototype.

While visually similar to an S1000RR beam frame, it’s internally quite different. Last year’s patent shows that there’s a structure of ‘pultruded’ square-section carbon tubes inside each frame rail and BMW’s experience in the area is unparalleled. Back in 2003 the firm developed pioneering techniques to mass-make carbon fibre structural components for cars. Just as the HP4 Race is a limited-edition machine, the first car to benefit was the limited-run 2003 M3 CSL, which had a carbon roof. On the following generation of M3 coupe, from 2007, the carbon roof was standard. In 2013 the firm launched the i3, an electric city car with a full carbon-fibre monocoque and a mainstream price tag, and the latest 7 Series luxury cars all use similar tech.

Ducati’s 1299 Superleggera is similarly being produced next year in small numbers, but it wouldn’t be a shock if the Panigale’s replacement – expected in 2018 – features a carbon chassis, at least on higher-spec models. Ever since the Panigale first appeared with its radical monocoque chassis, a carbon version has been expected. In fact, the chassis concept’s roots are in the carbon-framed Desmosedici GP9 of 2009, and when the Panigale was shown in November 2011, many expected the higher-end versions to get a carbon monocoque. It’s taken five years to happen, but those expectations are now being fulfilled.

Like BMW, Ducati’s parent firm (the VW Group) has plenty of composites experience. The firm also owns Lamborghini, which makes carbon-monocoque road cars, albeit not in the mass-production BMW fashion. Don’t be surprised if all high-end Ducatis come with carbon frames in a few years’ time.

If it’s so good, why doesn’t Márquez use it?

Carbon fibre frames have been less than successful in racing, but that’s no reason to write the idea off when it comes to either roadbikes or future racebikes.

The oft-quoted reason for carbon’s lacklustre race records is it’s too rigid, it doesn’t provide the imperceptible flex of a steel or aluminium chassis, and either leaves riders lacking on-the-limit feel or exacerbates problems like chatter.

Carbon structures can be developed with flex if needed, but it’s a learning process and no manufacturer has stuck with the material long enough to iron out every wrinkle. The real issue is that there’s a minimum weight limit in MotoGP which eliminates carbon’s main advantage. Roadbikes have no such minimum weight restriction. Ducati is claiming that its 1299 Superleggera is only 165kg ready to ride (154kg dry). That’s nearly as light as a MotoGP machine (157kg minimum weight) and the Superleggera manages it with a larger engine, lights, mirrors, indicators, a catalytic converter…

Road riders are never likely to reach that last fraction of a per cent where they’re relying on flex to feel whether the bike’s losing grip, and even if they are, the latest traction control technology and cornering ABS makes it far less of an issue than it was even in 2011 when Ducati last raced a carbon-framed GP bike.

By Ben Purvis