The term ‘superbike’ was a term loosely applied to any big-bore roadster of the late 1960s or early 70s, like the Honda CB750, Kawasaki H2 750, Triumph Trident, BSA Rocket 3, Norton Interstate or Commando, and the Kawasaki Z1. The name was ripe for the picking by a smart race promoter.

Early-70s race grids in sun-drenched Australia were bursting with a mix of production-based endurance bikes, Ultra-Lightweight, Lightweight, Junior and Senior grand prix classes, Formula 750 racing and, in early 1973, a new category: Superbike. But strong as they were, all these categories would become extinct – except for one. Superbike, which originated in Australia then spread throughout the world, outlasted the others and remains the premier class in every major national championship.

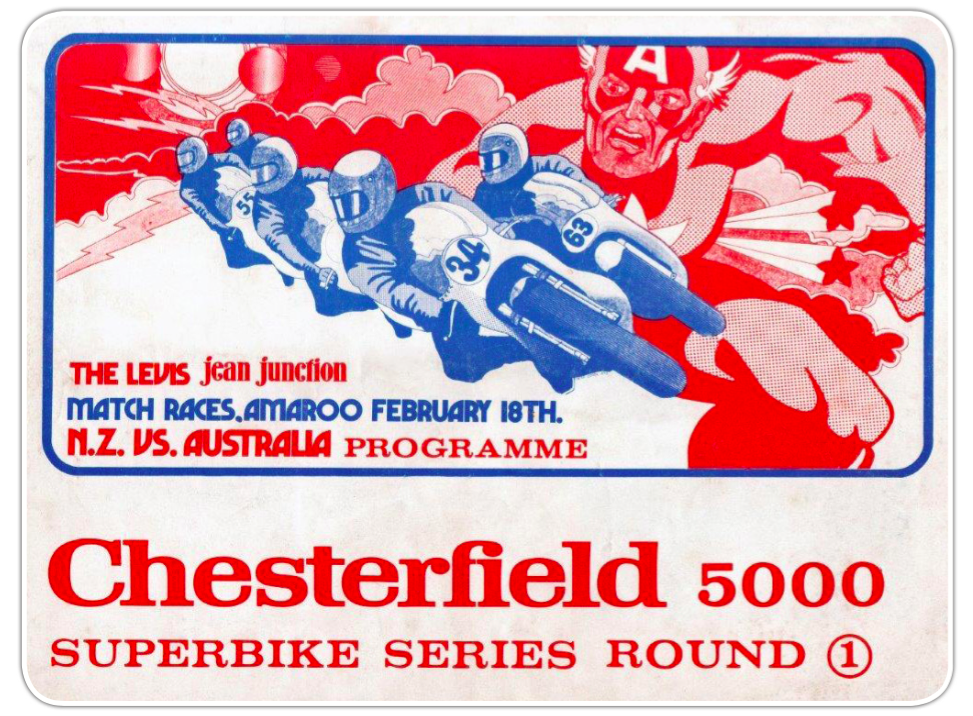

Born almost by accident out of the production- racing boom in Australia, and the improved production classes of the late 1960s, Superbike racing had a well-funded but rocky start thanks to an eclectic motorcycle club and an entrepreneurial member. Based on Sydney’s lower north shore, the Willoughby District Motor Cycle Club (WDMCC) employed a full-time secretary, Vince Tesoriero, a one-time club motocross rider, who was the creator of a number of historically important race promotions. The first was the 1970 Castrol 1000 Six Hour race for production motorcycles, and later this led to the Chesterfield 5000 Superbike Series.

“I first started to talk about a series for an Improved Touring spec class of racing in early 1972,” says Tesoriero. “The idea came from the fact we were already running the Castrol Six Hour – a race that was very strictly scrutineered to ensure only absolutely standard bikes competed.

“A lot of the riders were pushing us to allow changes that would make the bikes more rideable, with modifications to improve ground clearance and performance. We resisted because we wanted the Six Hour to be a ‘win on Sunday, buy on Monday’ concept.

“Eventually, I started to think about how good it would be if the basic roadbikes looked externally standard but you were allowed to do whatever inside. Plus raise footpegs and run whatever exhaust systems. At the time there was not a class of racing like this anywhere else in the world.

“I needed to give the new class a name and I started thinking about Super Bikes for Super Riders. Then I coined the name Superbikes. I went to Rothmans in Sydney, and pitched the sponsorship idea mid-1972 and they suggested the Chesterfield brand.”

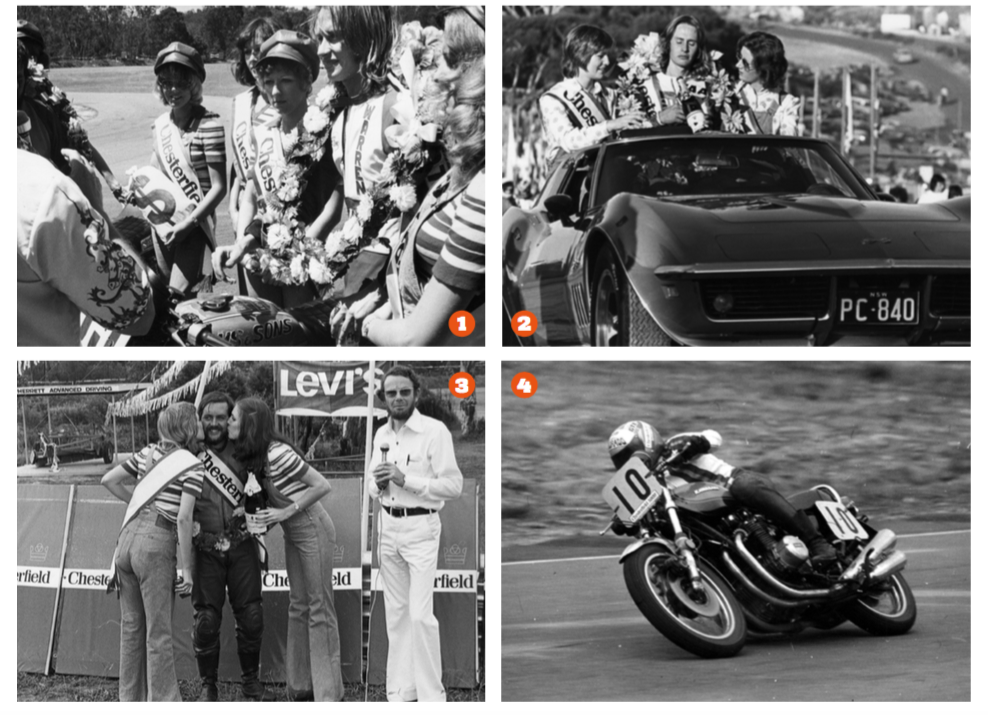

The Chesterfield Series race format was completely new too. It was open only to A-grade riders facing off in four sprints of four laps each at Amaroo Park. This format, combined with the sponsor gave rise to the nickname ‘Fag Drags’. Each race lasted little more than four minutes – the lap time of some circuits in Europe. The action was fast and furious, but the series experienced more than a few hiccups along the way.

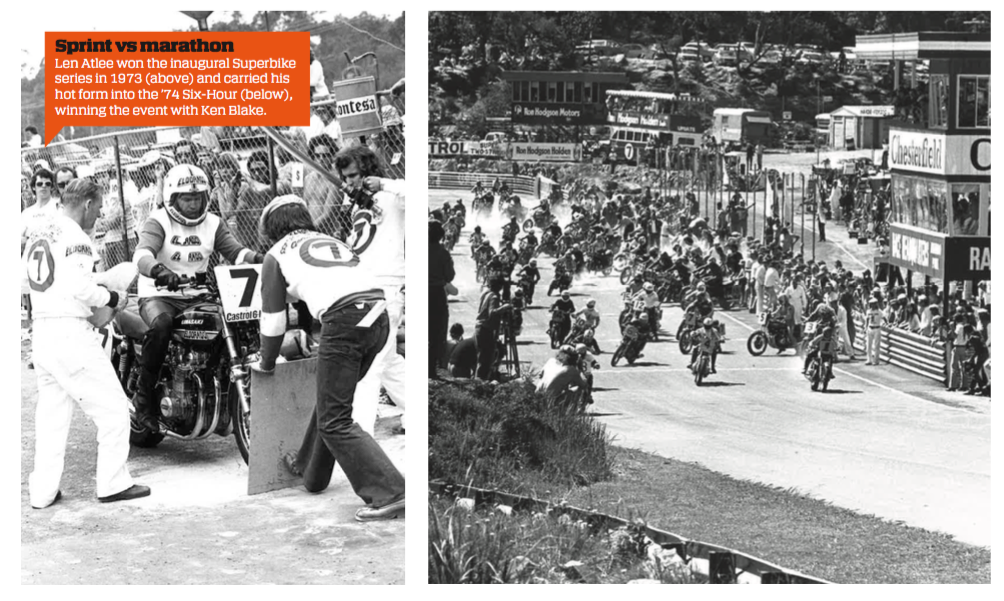

First-year winner Len Atlee’s bike came straight out of the Willoughby Superbike manifesto – it was a Norton Interstate 750 production racer souped up for Superbike racing. Norton-Villiers and BSA- Triumph merged on 16 July 1973, and around the same time the idea began to catch on that a Superbike class would help stymie cheating in production racing. Tesoriero announced that the WDMCC would impose severe penalties on those who transgressed, including an unprecedented sanction: life bans.

This edict coincided with the fourth round of the 1973 Chesterfield series. The opening round was made void following the too-smart-by-half interpretation of the rather loose rules that allowed Garry Thomas’ thinly veiled Yamaha TR3 grand prix bike to dominate.

WDMCC was forced to disqualify all the riders from claiming progressive points at the first round because “half the field ran in an illegal form”. Prize money was paid, but since the series was based on five rounds with riders dropping their worst score, every entrant automatically dropped their first round points.

According to Thomas: “The original rules were that the bikes had to be ‘externally standard’, so I took my Yamaha TR3 and fitted the seat and front mudguard off my R5 [350cc road-bike], and road wheels. I cleaned up at the first round, so Willoughby tightened the rules and made the class strictly production-based for the remainder of the series. So I reversed the situation – I used the R5 as the base and put on the TR3 pipes and whatnot that was allowed. Mind you, I had a lot of telephone conversations with Vince Tesoriero to determine what was actually in or out. I took the bike to Bathurst, but I broke my wrist on my 125 after it seized, so I didn’t get to race it there.”

In round two, Ron Toombs brought the Ross Hannan-built Honda CB750 with a thousand dollars’ worth of additional engine modifications. Clive Knight, second-place getter at round one, stretched his CB750 out to an 1100. The third round at Bathurst was boycotted by most A-grade riders due to prize money and fee disputes, with the win going to Bob Mayes aboard a Kawasaki 900.

The Chesterfield Series was hardly off to a flying start. As reporter Brian Cowan reflected after round four, “Like most ideas, the series had a difficult birth. The first round was spoiled by an incursion of thinly disguised Yamahas [GP bikes], a result of a liberal interpretation of the rules, and a certain amount of first-night nerves on the part of the Willoughby club.”

But round four doused any doubts about the strength of the Superbikes concept and the willingness of the combatants. “At the end of four lunatic four-lap races [there were] three riders of three different bikes – two British and one Japanese – and one point separating them,” reported Cowan on this occasion.

“The winning margins ranged from one second to a bike-length, and the crowd went home with the firm intention of coming back to cheer on their particular favourite in December’s vital final.”

The two stars of the round were Len Atlee, and Max Robinson, who made a clean sweep of all four sprints on his newly crafted Kawasaki Z1-900. Robinson had dazzled spectators and rivals alike with his breathtaking slides aboard a CB750 in the earlier rounds, and these were made all the more lurid on the Zed. He reeled off a stunning 59.9 sec lap in the last sprint that started in a drizzle, 1.8 seconds faster than the Unlimited Production record for which his Kawasaki was eligible. Atlee’s Ryan Motorcycles Norton 750 managed to harry Robinson in every race to card four second-place finishes. Dave Burgess recorded a 4-3-4-3 aboard his Hazell & Moore Triumph Bonneville to join Atlee in equal second in the overall standings with 63 points, just a shade behind joint leaders Atlee and Mayes on 64.

Although the death rattles of the British motorcycle industry were sounding across the world, Atlee and Burgess were keeping the Union Jack flying high Down Under in the face of the faster and technically superior Japanese bikes that were rapidly filling the grids. Atlee performed near miracles to keep the ageing Norton on par with Robinson’s Z1 – he recorded the fastest lap in race one of 60.7 and shared the honours with the Japanese four in race three.

The Yamaha 350s had trouble keeping up with the big bangers, Rob Hinton decking his 350 at Repco (later Mazda House) corner only be to run over by Thomas’ Leo Pretti 350, the former sustaining a broken hand, the latter also biting the dust along with Bruce Ireland (Bayliss Honda 750). Most of the field ran on methanol, with the rest on petrol, while later some fairly rocketed along on nitro. Sadly, Robinson was killed in a car crash en route to the Calder Two-Hour in August. Atlee became the inaugural champion.

The Chesterfield Series would survive just three years, hitting the wall in 1975. Although the racing was extremely hard fought and crowds plentiful, the number of entries had not grown since 1973. As a single-circuit promotion, it failed to attract many interstate entries. Australia was in a grip of the endurance racing production craze, so the Chesterfield Superbike series slipped between the cracks of long-haul production events and Grand Prix/F750 budgets.

Still, the series went out with a bang remembers Vince Tesoriero. “One of the best races I ever saw was Warren Willing and Garry Thomas in a Chesterfield Superbike run-off. They tied on points so I made them decide it on the track – a three-lap winner-takes-all race for $4000. You have never seen so many lead changes in one lap in your life.”

Thommo walked away with the cheque, the value of the average annual wage at the time.

3. Willing and his superhot Kawasaki H2 was a winning combo

AMA Superbikes

one brand. It later launched its ground-breaking CB750K1 in 1969, sparking a road-going superbike revolution across the world.Like any governing body, the AMA derives a large part of its income by issuing race licences. By 1970, Japanese brands accounted for more than 85 per cent of the American motorcycle market, and British bikes just five per cent. Production racing would open up a lucrative new group of riders to racing in the world’s biggest motorcycle market, but the rules tended more to the British relaxed approach – production racing that allowed full fairings and other mods in events like the Thruxton 500, rather than the pure philosophy used for the Castrol Six Hour.

Footrests could be re-located in the AMA production classes, and handlebars were open as long as they were bolted to the original mounts, leading to most competitors fitting those cool drop-style items.

Race tyres were allowed, but curiously, all lighting had to be fitted and operating at technical inspection, with lenses taped for racing as witnessed by the big field at the Willow Springs 12- Hour in 1968.

It was America that would create a major milestone in the Superbike story in 1976 with the world’s first-ever national production-based Superbike championship, although there is contention about that. American race historian Larry Lawrence says that he can find no record of the AMA sanctioning a national US Superbike Championship for the start of the 1976 season. He believes that the AMA merely tallied the individual Superbike events at the end of the short three-round series and declared Reg Pridmore the inaugural winner of the AMA Superbike Production Championship.

Back in Australia, after two years of racing under the ‘Superbike Touring’ banner at Bathurst, the class was finally headlined Superbike. The name stuck after the 1978 ACCA (now MA) conference approved a set of GCRs for a national Superbike class commencing in 1979, following the successful launch of the Victorian Superbike championship.

Remarkably, Australia only beat America by four months in staging a production-based Superbike-type event at a national meeting. The inaugural Chesterfield 5000 Series began in February 1973 at Amaroo Park, and the AMA national road race at Laguna in June.

In America, its modified production bike class was known as Open Production pre-1976 for both Heavyweight and Lightweight classes.

Adopting the term ‘Superbike Production’ to replace ‘Open Production’ famously happened after a conversation between AMA racer and World Superbike instigator Steve McLaughlin and Warren Willing at Ontario in 1975, Willing telling McLaughlin about the recently defunct Chesterfield 5000 Superbike Series.

Steve thought the word Superbike was “quintessentially” American, and advised the AMA to use it. It named the class Superbike ‘Production’ to avoid any confusion caused by previously promoting F750-type machines as ‘Superbikes’.